Design and construction of a social media corpus: Influencers’ speech in vlogs

Design and construction of a social media corpus: Influencers’ speech in vlogs

Hülya Mısır

University of Birmingham / United Kingdom

Abstract – Abstract – This article outlines the creation of a social media corpus of Turkish vlogs on YouTube, aimed at analyzing the translanguaging practices and multimodal communication of Turkish social media influencers. It firstly describes the process of constructing the corpus, including transcription conventions and ad hoc annotation. The article then analyzes the phenomenon of translanguaging, with an emphasis on its prevalent forms and modes. Given the challenges associated with compiling a multimodally rich social media corpus, this paper provides strategies for manually transcribing and annotating linguistic and semiotic features in ELAN software, as well as strategies for managing tier-based annotations for vlog datasets. Additionally, the study presents approaches for handling non-standard linguistic codes and marked occurrences in language contact zones, illustrated through examples drawn from the vlog corpus where Turkish serves as the standard code.

Keywords – social media corpus; corpus design; corpus construction; vlog; influencer; translanguaging

1. Introduction1

Working with social media data is often challenging due to its messy nature, typically characterized by a high degree of noise and heterogeneity. Hence, data from the web as a corpus requires rigorous attention to the processes of corpus design, data collection, balance and representativeness, and pre-processing. Although various software and online platforms have emerged to streamline the collection and analysis of web-based corpora, the protocol for compiling corpora from the Internet may be more intricate than that of working with traditional written or spoken data. This is because web-based data is translocal and multimodal, which adds a layer of complexity to the decision-making process.

In the digital media landscape, communication is a multifaceted process that transcends linguistic and semiotic boundaries. Digital discourse often defies the constraints of a single language or mode of expression. Users have embraced the practice of combining their linguistic repertoires, engaging in what I will later term ‘translanguaging’ to navigate the intricate web of digital interactions (Mısır and Işık Güler 2023). Simultaneously, the integration of various resources like images, emojis, and videos has enabled users to express themselves more creatively and effectively. The digital media environment presents a complex space for communication, one that demands an in-depth exploration of the multifaceted nature of language use in this digital context.

Studies have shown that the language of social media is intertwined with an array of semiotic and material resources (Jacquemet 2005; Blommaert and Rampton 2011). The specific form of social media discussed in this paper is vlogs. Vlogs feature a combination of speech, text, and multimodal elements such as emojis, subtitles, or audio and visual components additive to videos. Therefore, focusing on these ubiquitous resources as modes and explaining the significance of their role in mediated communication, and how they co-create meaning, becomes essential.

The present study describes the process of designing and building a corpus of Turkish social media influencers’ vlogs and shows non-standard language use and digital affordances used in interacting with an imagined audience by social media influencers. The corpus shows the features of real language-in-use evidenced by active content generators whose perceived influencing power is significant. However, corpora of the Turkish language, primarily spoken corpora, do not particularly take into account the expanding non-standard language use. This paper highlights a noteworthy aspect of non-standard language use, namely translanguaging, within the context of designing a corpus of contemporary language use. Translanguaging, as defined by Otheguy et al. (2015: 281), involves “the deployment of a speaker’s full linguistic repertoire without strict adherence to the socially and politically defined boundaries of named (typically national and state) languages.” In light of this diverse linguistic phenomenon, the challenge arises when devising annotation schemes for their incorporation into corpora. It is within the realm of corpus annotation that I descriptively demonstrate the pivotal role played by translanguaging. Specifically, I underline how its annotation becomes a critical concern in the context of computational analysis, as a substantial portion of social media discourse exhibits translanguaging, demanding specialized attention that can disrupt automation processes.

2. Vlogs and multimodal digital communication

Vlogs (video + blogs) are audiovisual forms of blogging conventionalized on YouTube. Vlogs are considered self-mediated quasi-interaction, and have interactional patterns (i.e., one-to-many) that feature “mass-mediated monologue” performances (Dynel 2014: 41). Vlogs dominantly consist of user-generated content and are typically characterized by unscripted, informal monologues delivered by the vlogger, who serves as both the content creator and the vlog’s subject (Frobenius 2011).

This style of content creation challenges traditional communication norms by introducing a new kind of audience ––an ‘imagined audience’–– in the digital sphere. As a result, it transcends the boundaries of conventional language codes and communication modes, encouraging a shift away from a mere focus on “languages as distinct codes” (Zhu and Li 2020: 15). Linguistic investigations of these forms of contemporary mass communication and linguistic behavior in online social interaction have contributed to a broader understanding of language, emphasizing a global discourse of “translingual hybridity” (Kramsch 2018: 113).

In digital landscapes, individuals develop diverse multimodal ecosystems, accommodating various combinations of linguistic repertoires. Translanguaging theory is a responsive approach to this heterogeneity and superdiversity with its focus on the flexible and creative use of linguistic resources and vibrant linguistic repertoires (Li 2011). It acknowledges the interplay between people’s repertoires, virtual repertoires, and general linguistic practices within communities, which organically evolve through lived experiences. Blommaert (2008: 16) emphasizes that language use in this digital age is not confined to any national or stable linguistic framework but is intimately tied to an individual’s life journey, following the unique biographical trajectory of the speaker. This perspective shifts the focus from language as a rigid construct to an emphasis on the speaker’s linguistic repertoire and practices.

In examining these contemporary mass communication and linguistic behaviors within online social interactions, it is essential to delve into the essence of multimodality, a concept that encompasses various resources for message composition, including textual, aural, linguistic, spatial, and visual modes (Schmidt and Marx 2019). Multimodality in social media communication can explain how users leverage this diverse range of resources to enhance the expressiveness and impact of their content, creating rich and engaging digital discourse. Scholars have increasingly recognized the importance of multimodality in digital communication, especially in content-driven environments like gaming (Schmidt and Marx 2019) or vlogs (Lustig et al. 2021). These studies explain how language, gaze, gestures, posture shifts, and the visual frame coordinate intermodally to make meanings by exploring people’s relations with their domestic (material) environments. In the context of vlogs, a multimodal approach can foreground typical vlogging locations and settings, which play a central role in constructing the visual aspects and characteristics of vlogging with the regularized spaces and commodities. Multimodal elements are crucial for ensuring the integrity and effective presentation of the communicated content. As such, merely analyzing the transcribed texts of vlogs does not adequately capture the meaningful whole or flow of the expected turn-taking. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of the communication dynamics at play, it is essential to examine the accumulated repertoires of means and modes employed by vloggers and how they are coordinated in the communication process.

3. Corpus design and construction

In the present study, I describe the design and construction of a corpus of Turkish social media influencers’ vlog content on YouTube. The influencers were selected through criterion sampling. The criteria include 1) speaking Turkish as their first language, 2) being based in Turkey as stated in the YouTube profile, 3) having a follower count of over 250,000 on Instagram and YouTube, 4) being an active content generator at the time of the data collection, and 5) having accounts open to public view. A noteworthy aim was to obtain an informed idea about the design features of the platform from which one collects data for the ‘representativeness’ of the corpus. Having applied this line of criteria, I aimed to represent the language and practices of macro-influencers, i.e., those who have a large number of followers and are represented by a professional agency, which indicates their established ‘enterprise’ status in the influencing market in Turkey.

Additionally, YouTube vlogs are categorized as synchronous (‘go live’) or asynchronous (‘upload video’). The former, characterized by real-time interaction with the audience, prioritizes instant feedback, audience engagement, and unaltered content dissemination. By contrast, the latter entails the creation of pre-recorded, edited, and strategically planned video content. These two vlogging modes exhibit noticeable disparities in both structural organization and operational approaches, potentially giving rise to variables in corpus analysis attributable to the diverse characteristics inherent in synchronous and asynchronous vlogging. Hence, this study exclusively examines asynchronous vlogs to achieve the representativeness of curated content where the content creator has complete control over what they want to share. They are more likely to reflect the creator’s intended message and image.

The specialized snapshot corpus of Turkish influencers’ communication contains 120,928 tokens of transcribed speech in vlogs posted between 2020 and 2021. The YouTube vlogs were chosen in chronological order of posting to avoid any bias in selection. However, videos that were three minutes or less, such as music clips, were not considered vlogs and were excluded irrespective of their posting order. The corpus design is presented in Table 1. A dataset of 30 videos was compiled by gathering five videos from each influencer’s profile. The footage length ranges from 13 to 42 minutes. In the construction of the corpus, I considered video length and token count as critical criteria. Balancing by token count was important to ensure an equitable representation of each participant and context within the linguistic data. However, it is important to note that there exists a natural trade-off between video length and token count. Longer videos tend to contain more tokens, yet they may also include extended periods of silence or non-linguistic elements. In contrast, shorter videos, while having a smaller token count, can offer a more concentrated source of linguistic information. Recognizing this trade-off, I aimed for a balanced approach, opting to equalize both video length and token count.

|

ID (Number of transcribed vlogs) |

Total footage |

Tokens |

|

DO (5) |

120 mins 29 sec |

19,056 |

|

EL (5) |

113 mins 39 sec |

18,179 |

|

DB (5) |

130 mins 38 sec |

22,834 |

|

KD (5) |

124 mins 49 sec |

17,549 |

|

EF (5) |

140 mins 36 sec |

22,851 |

|

MO (5) |

127 mins 09 sec |

20,459 |

|

Total (30) |

757 mins 20 sec (12hs 37 mins) |

120,928 |

Table 1: The details of the vlog corpus

The data was processed in ELAN (V.6.2; Wittenburg et al. 2006), a free tool for developing annotation and creating relationships between tiers. The software can incorporate speech segmentations in a time-aligned manner, transcriptions, part-of-speech annotations, and a limitless range of other modes annotated on different tiers. Such features facilitated surpassing the fundamental restriction of representing “all features of communication through the same mode ––that of a textual record” (Knight et al. 2009: 2).

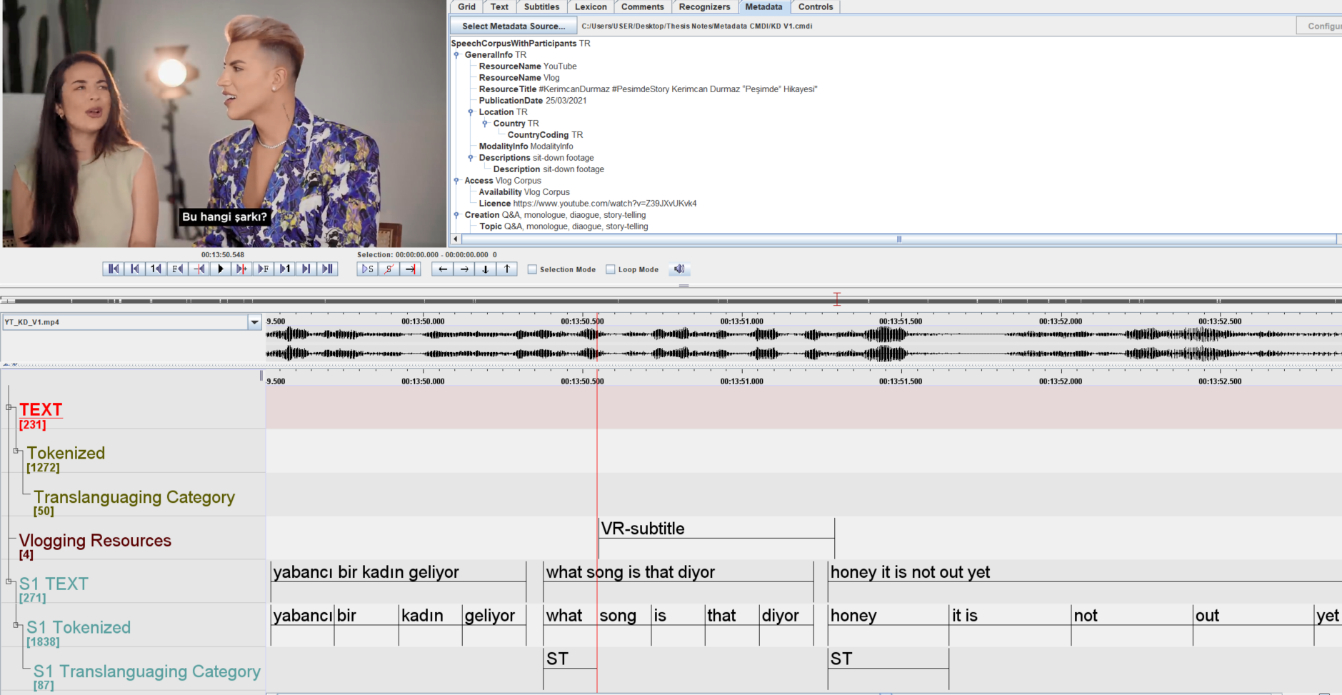

In ELAN, I initiated my workflow by importing videos and employing a predefined template that I had set up to maintain consistency across files, following the same annotation tier scheme. This standardized approach proved highly practical, particularly when applying the identical template to all videos, ensuring the comparability of tiers during the analytical phase. The annotation tiers consisted of 1) text, 2) tokenized tier, 3) translanguaging categories, 4) vlogging resources, and 5) consistent tiers for each participating speaker in the interactions. Each tier had a hierarchically sorted parent tier.

In processing the data, I worked in the annotation mode in ELAN to create utterance boundaries for 30 videos, deciding where the utterance began and ended. This segmentation process facilitated the transcription process and transcript alignment at the utterance level in the following steps. Upon completing the transcription on a tier called ‘Text’, the tokenization of this tier was performed automatically, which created a tier to place tokens individually. I created this tier to annotate translanguaging instances concerning the place of the token rather than the utterance as a complete line.

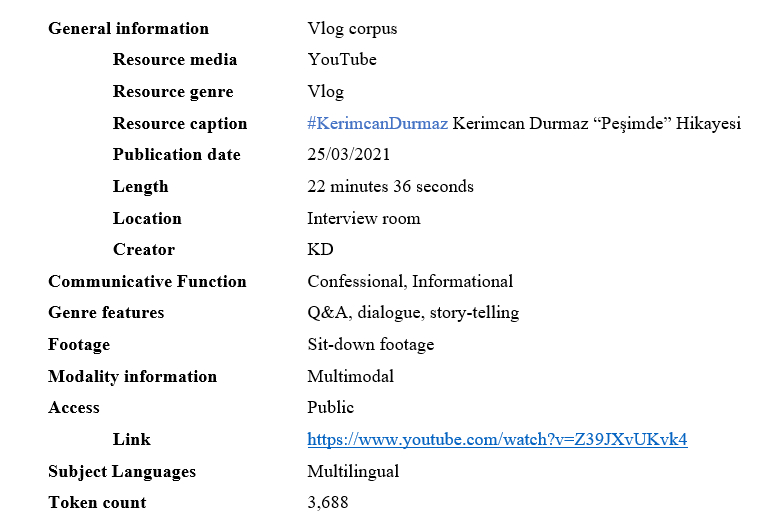

ELAN also supports metadata storage. Metadata from social media is shaped by what information is embedded in the structure of the platforms. For YouTube, metadata can be categorized into three types: a) automatically generated metadata (URL, date posted), b) semi-automatically generated metadata generated by clicks (metrics of views, dis/likes), and c) self-generated metadata (channel name, caption); see Schmidt and Marx (2019: 134). For this study, metadata included categories (a) and (c) and excluded the interaction data (b). Figure 1 shows a sample vlog metadata scheme formed in CMDI format, a relatively customizable format to display metadata in ELAN. Apart from the descriptive information in metadata categories (a) and (c), the CMDI files contained communicative functions (confessional, informational, instructional), genre features such as setting and location (question and answer, interview room), and footage (sit-down, slice-of-life, and behind-the-scenes) of the vlogs, and corpus information, including token and type.

Figure 1: The metadata scheme in ELAN metadata display

While collecting data from YouTube, I regarded captions as integral and compositional elements. Their display on the software panel used for constructing the corpus facilitates a swift and comprehensive review of the elements contributing to the generation of meaning, thereby aiding in the subsequent analysis. The information contained in vlog captions through emojis or hashtags, such as BU EVİN ODASI YOK 🏕️🌳 | TINY HOUSE VLOG (THIS HOUSE HAS NO ROOM 🏕️🌳 | TINY HOUSE VLOG), is relevant to the interpretation of the compositional elements of digital communication.

The metrics of views, dis/likes, or comment counts are dynamic data that showcase the audience’s reaction and the content generator’s popularity. They demonstrate an overview of public engagement and content dissemination, which grants impact in the market for social media users like influencers. For this study, the metrics were merely examined for viewership and subscribership of each influencer in sampling influencers.

Transcription of audio-visual data is similar to that of audio data to a large extent. Based on the purpose of transcribing, different transcription conventions can be followed or developed to represent speech in written form. For example, applying general principles of orthographic transcription of a particular language suffices when the sole purpose of the corpus compilation is to produce a corpus of transcribed texts (Love 2020). For the vlog corpus, I largely followed the transcription system developed in the Turkish Spoken Corpus project.2 However, it is important to note that, along with evolving social media affordances, language practices have evolved and changed in a way that transidiomatic usage and translingual digital lexis entangle standardized language codes, which has resulted in new considerations and unique challenges to overcome in constructing transcription conventions.

Automated transcription processes in constructing corpora from the web, like auto-captioning, may seem useful at first. For instance, YouTube auto-captioning provides time-aligned subtitles for videos. The transcriptions feature several languages with varying degrees of accuracy rate. Although YouTube’s speech recognition quality is improving through deep learning algorithms (Bokhove and Downey 2018), for languages other than English, the success rate is unsatisfactory. The complex morphology of agglutinative languages like Turkish results in a high out-of-vocabulary rate, reducing the accuracy of automatic speech recognition (Arısoy et al. 2009). Hence, when automated captioning does not accurately communicate the intended message, and the transcription demands extensive manual repair, using them is not time efficient. Table 2 compares auto-captions and manual transcription of a Turkish influencer’s vlog, and the results clearly show that manual transcription serves better for the objectives of the present study. Each line needs multiple corrections, ranging from inaccurate morphological derivations and wrong/missing proper names and nouns to missing chunks of phrases, some of which are in a different language than Turkish. Auto-captioning fails to recognize that the short dialogue between <S1> (Speaker 1) and <S3> (Speaker 3) is English, further evidencing its limitations of approximating English+Turkish constructions to either code. Consequently, automated transcriptions seem to be of limited use, which makes manual work inevitable for building spoken corpora (Love 2020).

|

Auto-generated subtitles |

Researcher-generated subtitles |

|

25:01 artık çok yoruldum Ali domates aldı limon almadık a şu limonlar olay olay 25:08 asparagas Lara bak Ama bu ne ya Bu nasıl bilim o arkadaşlar 25:16 kız bir şey değil mi karaip korsanlarındaki Oh Kaptan ahtapot 25:23 Ya bu nasıl iman Allah aşkına eski Memories that garip garip garip sınav 25:31 gör Vay inanılmaz kokuyor Ali |

25:01 <S1> artık çok yoruldum Ali domates aldık limon almadık aa şu limonlar olay olay <S2> o ne 25:08 <S1> asparaguslara bak _ bu ne ya bu nasıl bir limon arkadaşlar 25:16 kız bu şey değil mi Karayip Korsanlar’ındaki o_ kaptan ahtapot 25:23 _bu nasıl limon Allah aşkına excuse me what is this <S3> fast-forwarded speech <S1> got it got it got it smells good 25:31 yeah when they <incomprehensible> <S1> wow inanılmaz kokuyor Ali |

Table 2: An illustration of the accuracy of auto-generated Turkish subtitles on YouTube3

In building a vlog corpus, addressing the transcription of colloquial speech posed a significant challenge, primarily stemming from irregular pronunciation of words and morphemes. Slang, foreign nouns, neologisms, non-standard pronunciations, deviations from standard pronunciation, discrepancies in foreign word pronunciation, and the disruptive effects of digital features like fast-forwarding, as Table 2 shows, would impede the automated search capacity of corpus tools. To overcome this problem, I made the strategic choice to establish a manual transcription system that prioritized standardization in each language code to promote accuracy and facilitate more efficient search capabilities. For searchability, I found that the best way to approach examples such as (1) was to represent English pronunciation and the agglutination in Turkish.

1. Loop bantlarımızı kullanıyoruz, bosu balllarımızı kullanıyoruz.

‘We use our loop bands, and we use our bosu balls.’

The ball is an English code pronounced as /bɔ:l/, yet the speaker falsely pronounces it as /bɔl/ without the elongation. Here, balllarımızı is represented as ball (English code) -lar (plural suffixation in Turkish) -ımız (first person plural possessive pronoun), and -ı (accusative case). If I transcribed the speaker’s pronunciation of ball, the representation in Turkish phonetics would be bol /bɔl/, which becomes bollarımızı (a non-word). However, since bol (‘abundant’), has a different meaning in Turkish, it would be confusing for a Turkish speaker until the co-text and context become clear. This type of talk is not uncommon in this corpus, which is addressed as translanguaging.

Other decisions included the use of apostrophes for proper nouns of non-Turkish origin (i.e., Wet and Wild’lar, ‘the Wet and Wild products’), the capitalization of proper names, the removal of false starts (disfluencies), and the transcription of fragmented meaningful phrases. Non-linguistic cues and phonetic representations of loan and foreign words (i.e., aplikasyon, ‘applications’) were also documented. Acronyms were capitalized as they appeared in the vlogs (i.e., TL/Turkish Lira, PT/personal trainer). In colloquial Turkish, morphological changes, particularly in root or ending forms, are common and can impact token counts. While colloquial usage is often conventionalized, phonetic variations like falan (‘so and so’) can inflate type counts. Hence, I combined the variations in colloquial use in all represented linguistic codes for searchability, and colloquial usage, such as in falan for every falan, felan, or filan, was standardized. Ambiguities in meaning or pronunciation were clarified with phonetic transcriptions using the IPA (e.g., /rɪəlslaɾ/).

4. Annotation of non-standard elements in context

Vlog data contain standard and nonstandard texts and visual materials in combination; therefore, establishing an ad hoc annotation scheme is critical for identifying these elements to guide the analysis. The annotation categories were created via a cyclical process in which five vlogs (16.6% of the data) were initially marked to observe the local occurrences and commonalities of translanguaging instances and construct an annotation scheme. To ensure reliability, an expert linguist was consulted to identify and evaluate the tentative categories corresponding to a set of observations of translanguaging instances in the corpus. She annotated three randomly selected vlogs using the existing ELAN template. Inter-annotator reliability was calculated in ELAN, and over 85 percent overlap was assured for each category. I identified the constituent elements to gain a thorough understanding of the factors that drive translanguaging by examining the recurring patterns of translanguaging practices. Based on the corpus data, I identified the following practices that realized the translanguaging phenomenon. The categories were annotated on the tiers labeled ‘translanguaging category’ by examining the parent tier tokenized in ELAN for each .eaf file, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: The segmentation and annotation of a vlog in ELAN

Translingual Insertion (TI) is a linguistic phenomenon that involves the prominent use of specific lexical items to represent or refer to global entities, such as commodities or places, that are relevant to the context of the speech event in vlogs. To illustrate this phenomenon, consider example (2), where an influencer in a decluttering vlog holds two makeup products in her hand and compares them uttering the names of the products in the original language and integrating an ablative case marker in Turkish (-dan ‘by’ in this translation) as relevant to the syntactic construction of the meaning.

2. Mesela şunlar birbirine muadil.4

‘For example, these are equivalent [products].’

Ee Groundwork <TI> ve Color Tattoolardan Dusk Doll <TI>

‘Uhm, Groundwork and Dusk Doll by Color Tattoo.’

Digital Lexis (DL) includes born-digital lexical items and English vocabulary with extended meaning in the digital context. Example (3) illustrates a digital lexis like with an extended meaning indicating netspeak and Turkish suffixes. The transformation of form, function, and meaning of such global items is what translanguaging explains.

3. Videomu beğenip likelayıp <DL> abone olmayı lütfen unutmayın.

‘Please do not forget to like [like] my video and subscribe.’

Different from TI, where speakers keep the original code in their speech, phonetic transliterations (TL) represent words from one code that uses approximate phonetic or spelling equivalence of another code. The annotation includes both commonly used phonetic TLs that function as borrowing and idiosyncratic phonetic TLs that emerged in interaction, as illustrated in (4)–(5).

4. Kovitten <TL> önce uzunca bir zaman evimiz yoktu.

‘We did not have a home for a long time before Covid.’

5. Ee crispy coconut rolls aa kıtır kokonat <TL> ruloları.

‘Uhm, crispy coconut rolls uhm crispy coconut rolls.’

Slang is a part of the speakers’ linguistic repertoire and represents exclusive usage regarded as idiolects and idiosyncratic expressions. The slang in the analysis includes new forms or meanings as illustrated in (6) and (7). Popi is a newly constructed lexical item where the word popular in English and -i ––which is an adjective-making suffix in Turkish–– are combined. Similarly, lubunya (a Lubunca word)5 and -lar (a Turkish plural marker) are far from a monolingual construction and thus annotated for their slang character.

6. Ya bence benim değil herkesin en beğendiği ve en popi <SL> serumu.

‘Well, I think this is not just my favorite serum but everyone’s favorite serum.’

7. Lubunyalar <SL>

‘Lubunyas.’

Interpreting as a resource for translanguaging (IN) refers to the co-occurrences of language equivalents. This annotation is theoretically based on Baynham and Lee’s (2019) dynamic account of translation that manifests as activity and practice in translanguaging space. IN shows interpreting activities that partake in the flow of translanguaging, especially in cases where interpreting occurs in the co-text of the source text, as shown in (8).

8. İşte mesela kajudan fermente böyle bir peynirimle yine plant based bitki temelli <IN> böyle bir İtalyan I am nut OK more daring than dairy diye bir peynirim var.

‘For example, I have this fermented cashew cheese and a plant-based Italian cheese called I am nut OK more daring than dairy.’

The spontaneous translanguaging (ST) category comprises discontinuous and unplanned language codes, encompassing instances ranging from isolated single token expressions in multiple languages, as in (9), to more extended turns, or expressions embedded in the context or co-text of Turkish, as in (10).

9. Bir adet tişört. Thanks. <ST>

‘A tshirt. Thanks.’

|

10. |

S1 |

Senin ağzına malzeme veriyorum. |

|

|

|

‘I have put the words in your mouth.’ |

|

|

S2 |

Whatever. <ST |

|

|

|

‘Whatever.’ |

|

|

S2 |

I will call you later. <ST> |

|

|

|

‘I will call you later.’ |

|

|

S1 |

Fine. <ST> |

|

|

|

‘Fine.’ |

|

|

S1 |

Film zaten benim hayat boyu yapmak istediğim şeydi. |

|

|

|

‘Making a film was already what I wanted to do all my life.’ |

Translanguaging is a multimodal phenomenon, yet as Blackledge and Creese (2017) point out, translanguaging studies have paid little attention to multimodality. In this study, I identified the existence of multimodal elements contextualizing the annotated translanguaging instances. This annotation required paying attention to the resources in the digital space and visuals embedded in the segment of the instance. The annotation tier is Vlog Resource (VR). Speakers use these digital resources to recontextualize communication and achieve specific social goals. To illustrate the prevalence and implications of these multimodal resources, commonly occurring vlogging resources in the corpus are annotated. Example (11) showcases subtitles as a semiotic element, which improves the interaction for better viewer engagement, as the speaker assumes a linguistic gap between her and the imagined audience.

|

11. |

1 |

S1 |

Dansçıların kendine özel makyaj sanatçısı var. ‘Dancers have their own make-up artist.’ |

#1 |

|

|

2 |

|

Taya Shawki, who was ee Ariana Grande’s best friend tour partner (#1) ‘Taya Shawki, who was, uhm, Ariana Grande’s best friend tour partner (#1)’ <VR- subtitle> Ariana Grande’nin en iyi arkadaşı ‘Ariana Grande’s best friend’ |

The subtitle is only one of the multimodal ways of making meaning in a digital context. Another example is (12), which illustrates multimodal meaning-making with textual and visual modes. The digital element is the real-time YouTube subscriber counter displaying numerical increments, and the textual elements in English such as subscribers counter, subscribe, like, and share. Using the global semiosis of the social media signifiers, S2 borrows credibility from YouTube with the red colored button subscribe, Twitter with the light blue colored button like, and Facebook with the darker blue colored button share. This semiotic element of social media discourse exhibits intertextuality with speech, as evidenced by the semantic frame that underlies its meaning.

|

12. |

1 |

S2 |

Şu an böyle. ‘Now it goes like.’ |

#1 |

|

|

2 |

|

(#1) Tak tak tak tak tak tak tak tak tak aboneler böyle artıyor da olabilir. ‘(#1) The subscribers may also be snowballing like tak tak tak tak tak tak tak tak tak.’ |

|

|

|

3 |

|

Umarım öyle olur. ‘I hope it goes like that.’ <VR-text+visual> |

In this study, the adoption of a bottom-up approach to annotating translanguaging instances led to creating ad hoc categories that can guide researchers working with social media corpora to investigate multilingual speakers’ language use and communication practices, since messy datasets such as multimodal and multilingual communication can be quite challenging in determining where to begin. Therefore, these categories can be regarded as temporary indicators of a macro phenomenon, and not as a taxonomy, and are used to catalyze an interpretation of the complexities of current language practices regarding contextual factors. In addition, ELAN facilitated the preparation of diverse output formats. For instance, CSV files enabled the automatic extraction of annotations within ELAN across multiple files. The integration of filters within this format enabled the precise extraction of specific tags. The Time-aligned Interlinear Text format demonstrated versatility and enhanced the presentation of transcriptions and annotations, making it the chosen format for sharing this vlog corpus, which is freely and publicly accessible.6

5. Conclusions

Translanguaging in vlogs serves as a reflection of real-world communication practices in digital spaces, presenting researchers with an opportunity to explore the evolving nature of online communication that transcends language boundaries. The diversity present in vlogs provides rich data with which researchers may explore the use of multiple languages within a single discourse. However, while the prevalence of translanguaging offers valuable insights, it also introduces challenges in natural language processing tasks. These challenges include difficulties in part-of-speech tagging, syntactic analysis, and parsing, due to blurred language boundaries and non-conventional sentence structures. Despite these challenges, the identified categories of translanguaging instances present researchers with a valuable resource for understanding and addressing these complexities. By transforming these challenges into opportunities for computational and corpus analysis, researchers can make more effective use of online content and in the context of digital sociolinguistics.

The vlog corpus represents a rich medium of communication that extends beyond spoken language, incorporating a range of semiotic and multimodal elements that are central to communication in social media. The visual framing of the vlog, which encompasses edits and mode-mixing facilitated by modern technological tools and editing techniques, plays a critical role in exploring the phenomenon of multimodal deixis within the spoken corpus. It is where vlog creators combine spoken language with visual cues, gestures, and other non-linguistic elements to convey meaning and engage their audiences. Hence, the findings of this study underscore the importance of taking a multimodal perspective when analyzing online communication practices.

In addressing the ethical considerations of using publicly available YouTube vlogs for research, I ensured that all content used was explicitly public, adhering to YouTube’s terms of service.7 I informed the influencers and their agencies about the research through emails and social media, explaining that their publicly available content would be used for academic purposes, without any scraping of follower data or commercial use. While I did not seek explicit consent, I suggest that using publicly available content does not typically require consent if the interaction is intended as a public performance and invites wider engagement and visibility. Vlogs form a promotional genre on YouTube, especially in the influencer market, with branding and business-promoting activities. Since influencers intend their work to be public, protecting autonomy, privacy, and confidentiality is less likely to be an obligation. Hence, they inhabit a less controversial ground since they publish in the public sphere and exercise advertisement-oriented content dissemination for work-related purposes as self-employed adults. Furthermore, I ensured that no sensitive content was displayed to avoid any risk of harm. Based on this stance, I made time-aligned transcriptions that contained both the translanguaging annotations as well as the URLs to the original YouTube videos, such that researchers interested in (Turkish) spoken corpora of social media may facilitate a broader spectrum of research endeavors. I emphasize that the publicly accessible version of the corpus contains my transcriptions, annotations, and YouTube URLs, but not media components (e.g., video files, screenshots). This decision primarily stems from practical considerations, particularly on the challenges associated with hosting large video files on alternative platforms, given that YouTube serves as the primary hosting service for the content.8

Several implications of building and using this vlog corpus may be drawn. Firstly, the vlog corpus includes asynchronous vlogs with beauty, fashion, and lifestyle content that are narrations of mundane activities, often monologic and informational in nature and promotional in content (i.e., a tour of a wellness center). The corpus can be studied for marketing discourse analysis and the reevaluation of interaction and monologue patterns in online communication, particularly in social media culture and language. This includes examining authentic language and linguistic styles. Secondly, in comparison to other corpora, the corpus may be used to analyze the effect on authenticity and style in language use caused by differences between synchronous and asynchronous vlogging modes. These differences are significant, as the structural and operational variations in the content creation process may lead to distinct linguistic patterns; the ways in which virtual interaction and audience engagement are engineered differently on each platform have implications for analyzing language used in real-time interaction versus edited content. Thirdly, using ELAN for annotation and organizing data in a multimodal fashion allows for a more holistic analysis of social media communication. Moreover, I argue that transcription conventions need to evolve to keep up with changing language practices, especially in the context of social media and translanguaging practice; we should evaluate how transcription conventions have traditionally been used and how they can adapt to the evolving nature of language in digital communication, and explore the challenges of automated transcription and its implications for researchers relying on these tools for building corpora or analyzing spoken language.

References

Arısoy, Ebru., Doğan Can, Siddika Parlak, Hasim Sak and Murat Saraçlar. 2009. Turkish broadcast news transcription and retrieval. IEEE Transactions on Audio, Speech, and Language Processing 17/5: 874–883.

Baynham, Mike and Tong King Lee. 2019. Translation and Translanguaging. New York: Routledge.

Blackledge, Adrian and Angela Creese. 2017. Translanguaging and the body. International Journal of Multilingualism 14/3: 250–268.

Blommaert, Jan. 2008. Grassroots Literacy. New York: Routledge.

Blommaert, Jan and Piia Varis. 2011. Language and superdiversity. Diversities 13/2: 3–21.

Bokhove, Christian and Christopher Downey. 2018. Automated generation of ‘good enough’ transcripts as a first step to transcription of audio-recorded data. Methodological Innovations 11/2: 1–14.

Dynel, Marta. 2014. Participation framework underlying YouTube interaction. Journal of Pragmatics 73: 37–52.

Frobenius, Maximiliane. 2011. Beginning a monologue: The opening sequence of video blogs. Journal of Pragmatics 43/3: 814–827.

Jacquemet, Marco. 2005. Transidiomatic practices: Language and power in the age of globalization. Language and Communication 25/3: 257–277.

Knight, Dawn, David Evans, Ronald Carter and Svenja Adolphs. 2009. HeadTalk, HandTalk and the corpus: Towards a framework for multi-modal, multi-media corpus development. Corpora 4/1: 1–32.

Kramsch, Claire. 2018. Trans-spatial utopias. Applied Linguistics 39/1: 108–115.

Li, Wei. 2011. Moment analysis and translanguaging space: Discursive construction of identities by multilingual Chinese youth in Britain. Journal of Pragmatics 43/5: 1222–1235.

Love, Robbie. 2020. Overcoming Challenges in Corpus Construction: The Spoken British National Corpus 2014. New York: Routledge.

Lustig, Andrew, Gavin Brookes and Daniel Hunt. 2021. Social semiotics of gangstalking evidence videos on YouTube: Multimodal discourse analysis of a novel persecutory belief system. JMIR Mental Health 8/10: e30311. https://doi.org/10.2196/30311

Mısır, Hülya and Hale Işık Güler. 2023. Translanguaging dynamics in the digital landscape: Insights from a social media corpus. Language Awareness 32/3: 1–20.

Otheguy, Ricardo, Ofelia García and Wallis Reid. 2015. Clarifying translanguaging and deconstructing named languages: A perspective from linguistics. Applied Linguistics Review 6/3: 281–307.

Schmidt, Axel and Konstanze Marx. 2019. Multimodality as challenge: YouTube data in linguistic corpora. In Janina Wildfeuer, Jana Pflaeging, John A. Bateman, Ognyan Seizov and Chiao-I Tseng eds. Multimodality: Disciplinary Thoughts and the Challenge of Diversity. Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter, 115–144.

Wittenburg, Peter, Hennie Brugman, Albert Russel, Alex Klassmann and Han Sloetjes. 2006. ELAN: A professional framework for multimodality research. In Nicoletta Calzolari, Khalid Choukri, Aldo Gangemi, Bente Maegaard, Joseph Mariani, Jan Odijk and Daniel Tapias eds. Proceedings of LREC 2006, Fifth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation, 1556–1559.

Zhu, Hua and Wei Li. 2020. Translanguaging, identity, and migration. In Jane Jackson ed. The Routledge Handbook of Language and Intercultural Communication. New York: Routledge, 234–248.

Notes

1 I would like to thank the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (Tübitak) for supporting my research, from 2018 to 2022, through the 2211-A National Ph.D. Scholarship. [Back]

2 https://std.metu.edu.tr/ [Back]

3 Underlining indicates deleted syllable(s). [Back]

4 All translations are mine. [Back]

5 Lubunca is an anti-language primarily used among gay male and trans-female populations in İstanbul. [Back]

6 https://github.com/hulyamsr/Social_Media_Influencer_Corpus [Back]

7 https://www.youtube.com/static?template=terms [Back]

8 In YouTube ’s terms of service, under Content on the Service it is stated that “Content may be provided to the Service and distributed by our users and YouTube is a provider of hosting services for such Content.” Based on these terms of service, the content remains public once it is uploaded for public view and disseminated by the users. [Back]

Corresponding author

Hülya Mısır

University of Birmingham

School of English, Drama and Creative Studies

Edgbaston

Birmingham

B15 2TT

United Kingdom

Email: h.misir@bham.ac.uk

received: May 2023

accepted: June 2024