Building LANA-CASE, a spoken corpus of American English conversation: Challenges and innovations in corpus compilation

Building LANA-CASE, a spoken corpus of American English conversation: Challenges and innovations in corpus compilation

Elizabeth Hanksa – Tony McEneryb – Jesse Egberta – Tove Larssona – Douglas Bibera – Randi Reppena Paul Bakerb – Vaclav Brezinab – Gavin Brookesb – Isobelle Clarkeb – Raffaella Bottinib

Northern Arizona Universitya / United States

Lancaster Universityb / United Kingdom

Abstract – The Lancaster-Northern Arizona Corpus of Spoken American English (LANA-CASE) is a collaborative project between Lancaster University and Northern Arizona University to create a publicly available, large-scale corpus of American English conversation. In this article, we describe the design of LANA-CASE in terms of the challenges that have arisen and how these have been addressed – including decisions related to operationalizing the domain, sampling the data, recruiting participants, and selecting instruments for data collection. In addressing these challenges, we were able to draw on and further develop strategies established in the creation of other spoken corpora (including the British English counterpart to LANA-CASE, the Spoken British National Corpus 2014) as well as to implement recent theoretical and technical innovations related to each step. We hope that this discussion can inform future projects focused on the design and construction of spoken corpora.

Keywords – spoken corpora; conversation; corpus compilation; LANA-CASE

1. Introduction1

Corpora can provide meaningful insights into language, and they have a wide range of applications in research, teaching, and beyond (McEnery and Wilson 2001). While a great number of written corpora exist, the number of corpora that contain spoken language is more limited, which is likely due to the additional demands on time, resources, and ethical considerations that compiling a spoken corpus entails (McEnery and Brookes 2022). However, recent innovations2 can help researchers overcome such challenges to a degree. For example, the compilers of the Spoken British National Corpus 2014 (Spoken BNC2014; Love et al. 2017), a large-scale corpus containing 11.5 million words of British English conversation, implemented some innovations in response to the challenges they confronted during the corpus compilation process. The work discussed in the present paper builds on such innovations as well as innovations from other recently compiled spoken corpora.

The present article reports on the early compilation phases of the Lancaster-Northern Arizona Corpus of American Spoken English (LANA-CASE), a large-scale corpus of American English conversation, which we are currently compiling to be made freely available for linguists and language teachers upon completion. At the time of writing, about 600 hours of conversation recordings have been submitted and over two million words have been transcribed, with the goal of collecting and transcribing eight to ten million words in total.

This project incorporates several innovations in operationalizing the domain (conducting a domain analysis following the recommendations of Egbert et al. 2022), sampling (adopting an iterative sampling process which captures gender, race/ethnicity, communicative purpose, and other demographic and situational variables), recruiting participants (through piloting various recruitment methods and selecting the most effective ones —such as social media— to invest in), and instruments used in data collection (utilizing data collection software such as Phonic that is adopted in a series of discrete steps). We describe how these innovations can help compilers of spoken corpora overcome practical challenges, using the first year of conceptualization and data collection for LANA-CASE as a case study. These challenges and innovations will be addressed in turn in Section 2 (domain analysis), Section 3 (planning the sample), Section 4 (recruitment), and Section 5 (instruments).

2. Domain analysis

Corpus design should ideally encompass what Egbert, Biber, and Gray et al. (2022) refer to as the “domain considerations” by describing the domain, operationalizing the domain, and planning the sample (see Egbert et al. 2022, Chapter 4). Within this framework, the first phase in building a corpus involves conducting a domain analysis. A key consideration within this phase entails first learning as much as possible about the target domain, or the real-world language domain that the corpus aims to represent. This step is followed by operationalizing the domain, which is done by identifying the set of texts from which the corpus can realistically be collected. The third step involves choosing a sampling method and collecting the sample of texts. Establishing the target domain and operational domain allows the researcher to evaluate the degree to which the operational domain represents the real-world domain, and the degree to which the corpus sample represents the operational domain. We followed these guidelines to describe the domain of conversational American English (i.e., the population of texts that the corpus will ideally represent) and the operationalized domain (i.e., the subset of texts we could feasibly collect for inclusion in the corpus). We use this framework to guide the design and compilation of LANA-CASE. In this paper we focus primarily on the second step of a domain analysis: operationalizing the domain.3

2.1. Definition of the target domain

The target domain for LANA-CASE is spoken American English conversation. We define ‘conversation’ as an interactive spoken exchange of any length which is co-constructed by interlocutors (Hanks in preparation). Conversation can refer broadly to a wide range of communicative exchanges. Examples include an interaction that serves purely social functions, such as much of the conversation captured in the Cambridge and Nottingham Corpus of Discourse in English (CANCODE; McCarthy 1998) as well as an interaction that helps accomplish a task, such as much of the conversation captured in the Michigan Corpus of Academic Spoken English (MICASE; Simpson-Vlach and Leicher 2006). American English conversation specifically takes place between interlocutors who speak a variety of English that is typical within the United States (U.S.). Conversation may take place between interlocutors of diverse individual identities or characteristics –– including such factors as age, race/ethnicity, and gender.

2.2. Description of the operational domain

The operational domain for LANA-CASE reflects the domain of spoken American English conversation in the following ways: it contains unplanned and unedited interactive spoken discourse that takes place in both face-to-face and remote modes between speakers of a variety of English that is typical within the U.S., regardless of individual identities or characteristics. However, it is restricted in that it includes only data from consenting participants who are 18 years or older, from participants who have lived in the U.S. prior to attending elementary school, and of conversations that take place between only two or three interlocutors. We discuss these decisions below.

We determined that segments of conversation must be recorded to be included in the corpus, and ethically, conversation should only be recorded with all interlocutors’ knowledge and prior consent. It is possible that the observer effect may result in some differences between the conversations included in LANA-CASE and unrecorded conversations that will not be represented in the corpus (e.g., Saha et al. 2023). Building upon the findings of Love (2020), we strived to increase the reliability of speaker identification when transcribing (i.e., the ability for transcribers to attribute speech to the correct speaker) by operationalizing the domain as conversation between only two or three interlocutors (see Love 2020).

As a way of operationalizing what it entails to speak a variety of English that is typical within the U.S., we decided that all conversations must be between participants who have lived in the U.S. since before elementary school. The reason for this decision is that self-identification of language background is an inconsistent measure, especially when considering the complex nature of language input, output, community, and identity (Davies 1991). We therefore opted to operationalize the domain in practicable terms by collecting data from only one (quite large) population of American English speakers, using criteria that are objective and can result in more consistent data. Specifically, we chose to collect data only from speakers who have lived in the U.S. since before elementary school and speak English as a primary language. Additionally, while participants can be interlocutors of diverse ages, race/ethnicities, genders, and regions within the U.S., only interlocutors who are at least 18 years old are eligible to participate to simplify the process of ensuring informed consent.4

Because conversation may refer to a variety of communicative exchanges, we have provided participants little guidance in terms of what types of conversation they may submit. The instructions we provide are limited on our website to the following: “record your group talking about any topic(s) while completing your day-to-day tasks (e.g., during drinks with friends, a work meeting, getting ready for the day, etc.) and communicate as you normally would.”

3. Planning the sample

Planning the sample required us to consider what and how much to sample. We discuss these points in this section by describing how sampling issues have been addressed in the compilation of LANA-CASE.

3.1. What to sample

We have planned the sample based on a) participant demographics such as age and b) situational characteristics such as conversation setting. Because sampling equally across all possible strata would not be logistically feasible, we streamlined the sampling process by defining selection and descriptive criteria for participant demographics, following the approach used in the British National Corpus 1994 (BNC1994; Aston and Burnard 1998).

The planned sample covers data from specific demographic groups that represent four key individual variables (‘selection criteria’); we also collect metadata that do not specifically guide our sampling but will be useful for corpus users (‘descriptive criteria’). The LANA-CASE selection criteria include: 1) age, 2) race/ethnicity, 3) gender, 4) geographic region, and 5) residential setting (urban/suburban or rural). These selection criteria were set in part to ensure adequate representation from demographic variables that could influence language (e.g., Labov 1997). We have built upon the demographic data collected in the Spoken BNC2014 by collecting information about participants’ race or ethnicity while also sampling based on gender, allowing participants to identify as any gender rather than restricting participants to a binary selection. The descriptive criteria include information about participant demographics: additional languages, educational background, and occupation. To avoid excess influence of linguistic features by a single contributor, the number of conversations that any individual participant can submit is limited to a maximum of four hours of conversation. The decision to limit each speaker’s contribution was taken to maximize diversity in the sample.

Although we have prioritized planning the sample based on participant demographics, we also collect metadata about situational characteristics of conversations: interlocutors’ relationship, setting (home, restaurant, etc.), and communicative purposes (using a list developed by Biber et al. 2021). We have adopted an iterative sampling process following Biber (1993) in which we consistently monitor the sample structure to detect imbalances in the submissions (e.g., to ensure balance across gender), which we have been able to address in recruitment efforts (see section 4).

3.2. How to sample

We aim to make LANA-CASE suitable for a wide range of research strands (e.g., quantitative analyses of lexicogrammatical features, qualitative analyses of pragmatics, analyses of sociolinguistic and register variation, discourse analysis, data-driven learning, lexicography, etc.). As such, we seek to build a corpus that is as large as possible, given inevitable constraints on time and funding. We expect that the completed corpus will be between eight and ten million words. The estimated size of each demographic sub-stratum has been established based on population data from the most recent U.S. Census (U.S. Census Bureau n.d.) with the goal of proportionally representing different ages, race/ethnicities, genders, demographic regions, and settings (urban/suburban or rural) within the U.S. These proportions provide rough guidelines as to a) the ideal proportion of our sample that should fall into each category (in the case of region and residential setting) and b) a minimum benchmark in terms of the representation from minority groups (in the case of participants’ age, race/ethnicity, and gender). The estimated proportions we have used to guide our sample are shown in Table 1. While it is unlikely that the data in the final corpus will fall into these estimates perfectly, they are guidelines which we have strived for in terms of recruitment.

|

Selection criteria |

Population |

Estimated proportion of selection criterion |

|

Age |

18–25 years old |

25% |

|

26–39 years old |

22% |

|

|

40–65 years old |

33% |

|

|

66 years old and over |

20% |

|

|

Race/Ethnicity (percent estimates account for intersectionality) |

White |

60% |

|

Hispanic or Latinx |

18% |

|

|

Black or African American |

13% |

|

|

Asian |

5% |

|

|

American Indian or Alaska Native |

2% |

|

|

Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander |

2% |

|

|

Gender |

Male |

47% |

|

Female |

47% |

|

|

Other (e.g., nonbinary) |

6% |

|

|

Geographical region |

South |

28% |

|

West |

24% |

|

|

Midwest |

21% |

|

|

Northeast |

17% |

|

|

Residential setting |

Urban/Suburban |

80% |

|

Rural |

20% |

Table 1: Proportion guidelines for data sampling

4. Recruitment

In order to approximate the sampling distribution described above, careful recruitment is necessary. Recruitment is a challenge in many studies (e.g., Farrokhi and Mahmoudi-Hamidabad; 2012 Dworkin et al. 2016), and it is further complicated in a project such as this where participant activities are relatively demanding (as this can mean fewer potential participants are willing to sign up), participants cannot participate in a single sitting (as this can lead to high attrition rates), and the researchers do not have easy access to the population of interest. We sought to preempt some of these issues by piloting different recruitment strategies (including some that had not been utilized in previous corpus compilation projects), aiming to build rapport with participants, and offering incentives. These are discussed in the following sub-sections.

4.1. Piloting recruitment strategies

We have explored which recruitment strategies are most effective at: a) recruiting many participants, b) recruiting participants from hard-to-reach populations, and c) recruiting participants with lower rates of attrition (i.e., participants who follow-through by submitting all materials over the course of several days or weeks). The list below contains the recruitment strategies we have piloted, with asterisks marking those that have been particularly effective and therefore warrant continued use.

In addition to these recruitment strategies, we are currently piloting several others, such as hosting recruitment events at restaurants, which we will report on upon completion of recruitment efforts. As can be seen above, the most effective strategies thus far have been posting recruitment videos on social media, offering extra credit to students, hosting conversation activities at assisted living centers, and recruiting personal contacts. Further information about how we have implemented each of these strategies, their effectiveness, and their strengths and limitations is provided in Table 2.

|

Strategy |

Explanation |

Effectiveness |

Strengths |

Limitations |

|

Posting recruitment videos on social media, including TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter |

A social media presence was initially established by posting five days a week (videos were created on TikTok and then shared to all other platforms). Many videos are specifically related to the project, inviting viewers to participate, while others are related to linguistics more generally to create more engagement with the channel and therefore boost rapport and overall viewership. |

45 percent of recorders were recruited through this method. 17 percent of these recorders then followed through with submitting at least one conversation. |

|

|

|

Offering extra credit to students for participating |

We have offered extra credit (i.e., bonus points that supplement a students’ overall grade in a course) to our university students for submitting 45–60 minutes of conversation. All participants receive credit for participating, whether they and/or their interlocutor(s) are eligible to contribute data to LANA-CASE or not, and whether they choose for their conversation to be used in the corpus or not. Linguistics faculties at other universities across the U.S. have implemented this strategy in their classes as well. |

11 percent of recorders were recruited through this method. 76 percent of these recorders then followed through with submitting at least one conversation. |

|

|

|

Hosting conversation activities at assisted living centers. |

We have hosted conversation activities at a local assisted living center during which time residents conversed with volunteer university students. The university students recorded the conversation and ensured all materials, including informed consent, were submitted. |

0.5 percent of recorders were recruited through this method. 100 percent of these recorders then followed through with submitting at least one conversation. |

|

|

|

Inviting personal contacts such as friends and family to participate (word of mouth) |

We have invited our own friends and family to participate. Recorders who have been remunerated also share this opportunity with their own personal contacts. |

12 percent of recorders were recruited through this method. 17 percent of these recorders then followed through with submitting at least one conversation. |

|

|

Table 2: Recruitment strategies

As shown, one of the most common limitations we have confronted in recruitment is high attrition rates, in which participants do not follow through by submitting all required materials after signing up. We have attempted to address this issue by sending participants (bi)monthly email reminders about the deadline for their submissions. Another challenge we have faced is limited diversity, as most participants are white and under 35 years of age. Social media has helped to alleviate this problem to an extent by reaching a broader audience of various races/ethnicities, and hosting conversation activities at assisted living centers has helped reach participants from older age ranges.

An additional step we have taken to recruit more participants who are over 35 years old and come from diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds is to collaborate with a market research panel who specifically recruits participants from underrepresented demographic categories, a recruitment strategy employed in the creation of the original BNC1994. While this endeavor brought in 364 recorders from hard-to-reach populations (17% of our total pool of recorders), only two participants followed through with submitting at least one recording. It is possible this method did not prove effective because market research panels have access to millions of people who are primarily motivated by monetary incentives. The incentive we offered may not have aligned with these individuals’ expectations in light of the activities we asked that they complete.

4.2. Building rapport

We have sought to build rapport with participants by sending them monthly emails with reminders about the status of their submissions, including how many minutes of conversation they have submitted and how many more are necessary for them to receive remuneration. We also keep an active presence on social media and send remuneration in a timely manner.

4.3. Offering incentives

In addition to building rapport, we have incentivized participants through monetary remuneration. Once their submitted conversations add up to two hours, participants receive an Amazon e-gift card. Recorders have the option to choose to receive the gift card or to donate it back to the project. While some have chosen to donate their gift card, many have elected to be paid. We also use monetary incentives to encourage participants to submit several conversations of various lengths. Each conversation submission enters recorders into a monthly raffle to win an additional gift card.

In addition, we work to incentivize participants by sharing ideas about possible applications of the corpus. For example, LANA-CASE could be used to create more equitable learning environments by comparing the language in textbooks to the language of Latinx and other racial/ethnic minority groups in the U.S. Recruits have responded to such ideas on social media with enthusiasm (e.g., “I LOVE LINGUISTICS. THIS IS SO COOL” and “Absolutely fascinating. I now love linguistics”).

Finally, since this is a long-term data collection process that is expected to last at least two years, we have encountered the need to incentivize participants to submit their conversation recordings promptly. Through monthly deadlines, we ask participants to submit their conversations by the 15th of the month for them to receive remuneration on the 16th. This has allowed for a steady flow of submissions that is necessary to adopt an iterative sampling process (see, e.g., Biber 1993).

5. Instruments

In order to collect recorded conversations from a large number of diverse participants across the U.S., we determined that creating instruments to allow for Public Participation in Scientific Research (PPSR; Shirk et al. 2012), following methods used in the Spoken BNC2014 (Love et al. 2017) and the National Corpus of Contemporary Welsh (CorCenCC; Knight et al. 2021), would be most effective. With the help of these instruments, participants followed instructions to record their own conversations and submit them along with all necessary metadata. When implementing PPSR in this way, clear yet simple instructions as well as easily navigable data collection instruments are necessary. This section describes steps we have taken to develop relatively user-friendly data collection processes and instruments.

We adopted a data collection process similar to both the BNC1994 (Leech 1993) and the Spoken BNC2014 (Love et al. 2017) wherein one participant signs up as a recorder to submit conversation recordings. Placing the responsibility of submitting recordings along with all required information on a single participant rather than a group enabled us to more easily contact the individual concerned and distribute remuneration to them. We believe that recruiting recorders —as opposed to groups— also allowed us to establish a workflow which encouraged submissions of more naturalistic conversations.

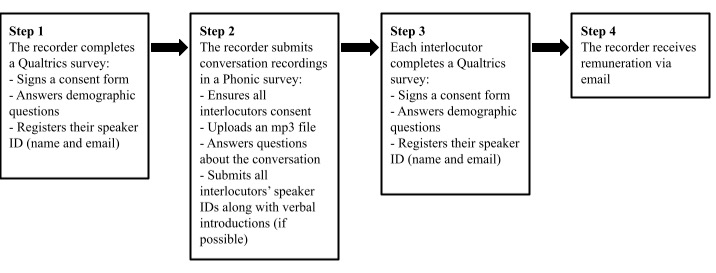

Recorders are directed to our website10 to learn more about the project and get involved. Once they decide to contribute data, they are asked to fill out three short electronic surveys. First, they take a two- to three-minute survey in Qualtrics,11 where they sign up, provide informed consent, and answer demographic questions about themselves. They are then encouraged to record their everyday conversations, specifically conversations that would have happened regardless of whether they were recording them (e.g., eating lunch with friends, cleaning the kitchen with a roommate, driving across town with a partner, etc.). The conversation recording(s) should be submitted as part of the second survey, hosted on the platform Phonic12 (phonic.ai) at their convenience. The Phonic survey asks that all participants introduce themselves vocally in a brief 15–second recording, to facilitate speaker identification in transcription. It is not until after the conversation is submitted that the recorder is asked to complete the third (and final) step: a demographic survey for the other participant(s) in the conversation. The full process is depicted in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Steps for recorders to participate in data collection

Before arriving at this data collection process, we had considered several other possible workflow models, such as requiring all demographic information to be submitted along with the conversation recording itself in a single survey as well as requiring all demographic surveys to be submitted before the conversation is uploaded. Although the final process we arrived at is more time-consuming in the post-processing stage than other possible work-flow models (because it requires matching the appropriate demographic surveys to each conversation), we believe it encourages participants to submit conversations that occur more naturally because recorders can begin recording conversations spontaneously with minimal intrusion while still submitting all required documentation.

We had also considered utilizing a crowdsourcing app for data collection. Yet, while applications have been shown to be effective tools for corpus creation (e.g., Knight et al. 2021), we determined a series of questionnaires to be better suited to our needs because downloading an application may a) require more commitment on the participants’ part, thus reducing the number of people who register and b) make it more challenging for participants not familiar with using such apps to participate.

Because this data collection process is demanding of participants’ time and energy, we sought to streamline the process as much as possible, which required balancing our desire for extensive metadata with participants’ possible aversion to lengthy surveys. Thus, the demographic survey contains minimal questions so that it should take participants up to only three minutes to complete (the full list of questions and answer options can be found in Appendix B).

6. Conclusion

There are many challenges associated with compiling spoken corpora, including those discussed in this paper as well as those that fall beyond its scope, such as transcription, part-of-speech tagging, and preparing data for public release. The challenges we have faced in the LANA-CASE project to date include: 1) planning the sample (sampling largely based on participants’ demographic variables), 2) recruiting participants (building rapport, providing incentives, and recruiting diverse and reliable participants), and 3) designing instruments (encouraging submissions of naturalistic conversations and using simple yet descriptive surveys). Each of these challenges has required creative problem solving. This has resulted in innovative approaches to corpus building, including carrying out a domain analysis (following Egbert et al.’s 2022 recommendation), sampling iteratively based on demographic and situational variables, recruiting participants by piloting several recruitment methods and investing in the most effective ones (e.g., social media such as TikTok), and adopting a new software called Phonic as part of a series of discrete data collection steps. Yet, as the process is still ongoing, we have yet to evaluate the success rate of our efforts. We also do not expect our decisions to be the only solutions to such issues; however, we do hope that they may stimulate further discussion and spark new ideas for future compilers of spoken corpora to build on.

References

Aston, Guy and Lou Burnard. 1998. The BNC Handbook: Exploring the British National Corpus with SARA. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Biber, Douglas. 1993. Representativeness in corpus design. Literary and Linguistic Computing 8/4: 243–257.

Biber, Douglas, Jesse Egbert, Daniel Keller and Stacey Wizner. 2021. Towards a taxonomy of conversational discourse types: An empirical corpus-based analysis. Journal of Pragmatics 171: 20–35.

Davies, Alan. 1991. The Native Speaker in Applied Linguistics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Dworkin, Jodi, Heather Hessel, Kate Gliske and Jessie H. Rudi. 2016. A comparison of three online recruitment strategies for engaging parents. Family Relations 65/4: 550–561.

Egbert, Jesse, Douglas Biber and Bethany Gray. 2022. Designing and Evaluating Language Corpora: A Practical Framework for Corpus Representativeness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Farrokhi, Farahman and Asgar Mahmoudi-Hamidabad. 2012. Rethinking convenience sampling: Defining quality criteria. Theory & Practice in Language Studies 2/4: 784–792.

Hanks, Elizabeth. (In preparation). Exploring the register of conversation: Uncovering linguists’ insights about its situational characteristics.

Knight, Dawn, Fernando Loizides, Steven Neale, Laurence Anthony and Irena Spasić. 2021. Developing computational infrastructure for the CorCenCC corpus: The National Corpus of Contemporary Welsh. Language Resources and Evaluation 55: 789–816.

Labov, William. 1997. Linguistics and sociolinguistics. In Nikolas Coupland and Adam Jaworski eds. Sociolinguistics: A Reader. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 23–24.

Leech, Geoffrey. 1993. 100 million words of English. English Today 9/1: 9–15.

Love, Robbie. 2020. Overcoming Challenges in Corpus Construction: The Spoken British National Corpus 2014. New York: Routledge.

Love, Robbie, Claire Dembry, Andrew Hardie, Vaclav Brezina and Tony McEnery. 2017. The Spoken BNC2014: Designing and building a spoken corpus of everyday conversations. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 22/3: 319–344.

McCarthy, Michael J. 1998. Spoken Language and Applied Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McEnery, Tony and Andrew Wilson. 2001. Corpus Linguistics: An Introduction. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

McEnery, Tony and Gavin Brookes. 2022. Building a written corpus: What are the basics? In Anne O’Keeffe and Michael McCarthy eds. The Routledge Handbook of Corpus Linguistics. London: Routledge, 35–47.

Saha, Koustuv, Pranshu Gupta, Gloria Mark, Emre Kıcıman and Munmun De Choudhury. 2023. Observer effect in social media use. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-2492994/v1

Shirk, Jennifer, Heidi Ballard, Candie Wilderman, Tina Phillips, Andrea Wiggins, Rebecca Jordan, Ellan McCallie, Matthew Minarchek, Bruce Lewenstein, Marianne Krasny and Rick Bonney. 2012. Public participation in scientific research: A framework for deliberate design. Ecology and Society 17/2: 1–20.

Simpson-Vlach, Rita C. and Sheryl Leicher. 2006. The MICASE Handbook: A Resource for Users of the Michigan Corpus of Academic Spoken English. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

U.S. Census Bureau. n.d. Explore census data. https://data.census.gov/(June 2022).

Appendix a: Terms and conditions

Project information

You are being invited to participate in a project titled The Lancaster-Northern Arizona Corpus of American Spoken English (LANA-CASE). Data collection for this project is being conducted by Jesse Egbert, Tove Larsson, Elizabeth Hanks, Doug Biber, and Randi Reppen from Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff, Arizona and Tony McEnery, Vaclav Brezina, Paul Baker, Gavin Brookes, Isobelle Clarke, and Raffaella Bottini from Lancaster University in the United Kingdom.

The purpose of this project is to create a resource for linguistic research. We are collecting samples of spoken American English that will be used to inform research into the English language as well as the development of teaching materials for language learners. The recordings will be transcribed and then made into a publicly available resource in both audio and transcribed (written) form.

Participant eligibility criteria

You are eligible to participate in this project if you speak English as one of your primary languages, have lived in the United States since before elementary school, and are at least 18 years old.

Participant activities

If you agree to take part in this project, you will be asked to complete several steps:

By participating, you agree that the research team has permission to store indefinitely, transcribe, and otherwise use recordings of your speech, and you agree that such data may be stored and used in perpetuity. You also agree that other researchers throughout the world have permission to use recordings and transcriptions of your speech for research and/or language teaching indefinitely.

Participant compensation

The recorder is eligible to receive a $25 Amazon e-gift card for every two hours of conversation that they submit as part of Step 2. The Amazon e-gift card will be sent to the email you provide. Payment will be sent on the 16th of each month until all necessary data has been collected. Only one recorder may receive remuneration for each two-hour block.

Each recording submitted will enter recorders into a drawing to win an additional $50 Amazon e-gift card. Results from the drawing will be publicized on the 16th of each month until all necessary data has been collected.

The following requirements must be met in order to be remunerated:

Protection of risks

As with any online-related activity, the risk of a breach of confidentiality is possible. We will minimize this risk by saving all data on an encrypted, password-protected server. Additionally, the research team will protect your privacy by removing personal information (such as references to people, places, and institutions) from the transcription. Your recording and transcription will be available only to researchers who have completed a data use agreement and are accessing the data strictly for research and/or language teaching purposes.

Your participation in this project is completely voluntary and you can withdraw at any time. If you choose not to participate, it will not result in any penalty or loss of benefits to which you are otherwise entitled.

Contact information

If you have questions about this project, you may contact the research team at ShareYourVoiceEnglish@gmail.com

* If recorders participate as a school assignment, they are eligible to receive class credit as determined by their instructor rather than monetary compensation.

Appendix b: Demography Survey

|

Question |

Possible answers |

|

Do you agree to the Terms and Conditions? |

Yes No |

|

Have you lived in the United States since before elementary school? |

Yes No |

|

Are you 18 years old or over? |

Yes No |

|

What is your birth year? |

[open-ended] |

|

What is your gender? |

Male Female Other (please specify): [open-ended] |

|

What is your race/ethnicity? (check all that apply) |

White Hispanic or Latino Black or African American Asian American Indian or Alaska Native Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander Other (please specify): [open-ended] |

|

What language(s) do you speak at home? |

English Spanish Other (please list the language(s)) |

|

What language(s) do you speak outside of the home? |

English Spanish Other (please list the language(s)) |

|

What is the highest level of education you have completed? |

Less than high school High school graduate Trade school certificate (e.g., electrician, commercial driver, cosmetology, etc.) Undergraduate degree Graduate degree |

|

What is/are your occupation(s) (e.g., nurse, student, construction worker, etc.)? |

[open-ended] |

|

What best describes your living situation? Feel free to add more details, if necessary. |

I live in an urban or suburban area I live in a rural area |

|

In what state do you currently live? |

[drop-down of all 50 states and Washington D.C.] |

|

Have you lived in one state for more than half your life? If yes, which state? |

Yes No [drop-down of all 50 states and Washington D.C.] |

|

Where did you find out about this project? (For example, Facebook, a flyer at a coffee shop, a friend, etc.) |

[open-ended] |

Notes

1 We gratefully acknowledge Lancaster University’s Global Advancement Fund, Northern Arizona University’s Faculty Course-based Undergraduate Research Experience Development Grant, the Northern Arizona University Corpus Lab, and Northern Arizona University’s SGS Award, whose support has made this project possible. We are also very grateful to our collaborators who have helped with recruitment and data management, contributors who have supported data collection, and participants who have submitted conversations. [Back]

2 For the purposes of this paper, we define ‘innovation’ as any methodological decision made that we have not seen implemented in the compilation of previous spoken corpora. [Back]

3 A full description of our target domain is beyond the scope of the present article and will be documented in forthcoming publications. [Back]

4 We have taken great care to ensure all participants in the corpus have provided informed consent. The Terms and Conditions each participant signs are available in Appendix A. [Back]

5 https://www.tiktok.com/@lana_linguistics?is_from_webapp=1&sender_device=pc [Back]

6 https://www.instagram.com/lana_linguistics/ [Back]

7 https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100088160239514 [Back]

8 https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCf8g41kI3d5QOov5RgxT9uQ [Back]

9 https://twitter.com/LANA_corpus?ref_src=twsrc%5Egoogle%7Ctwcamp%5Eserp%7Ctwgr%5Eauthor [Back]

10 http://tinyurl.com/yc4su4z5 [Back]

Corresponding author

Elizabeth Hanks

Northern Arizona University

College of Arts and Letters

English Department

S San Francisco St.

Flagstaff

AZ 86001

United States

Email: eah472@nau.edu

received: May 2023

accepted: February 2024