Nonbinary pronouns in X (Twitter) bios: Gender and identity in online spaces

Nonbinary pronouns in X (Twitter) bios: Gender and identity in online spaces

Lucía Loureiro-Porto – José Luis Ariza-Fernández

University of the Balearic Islands / Spain

Abstract – This study explores the usage of nonbinary pronouns on X (formerly known as Twitter), focusing on they and neopronouns like ze or xe within the nonbinary community. Building on the increasing practice of sharing pronouns, especially in online spaces, the research collects 1,980 X accounts using Followerwonk. Despite ideological differences across U.S. regions, no substantial variations in pronoun usage are observed. Notably, a preference for rolling pronouns (e.g., they/she) emerges, with fewer instances of monopronoun usage (e.g., they). When a single pronoun is chosen, it is often accompanied by the respective accusative form, while rolling pronoun users tend to omit the accusative. Users with binary pronouns often prioritize it as their first chosen pronoun. they remains the predominant nonbinary pronoun, with neopronouns being rare. The study highlights X profiles as valuable sources for understanding linguistic patterns related to social trends, particularly in the context of gender equality and network relations.

Keywords – nonbinary pronouns; singular they; neopronouns; gender-inclusive language; social media; X (Twitter)

1. Introduction1

The exploration of pronouns as tools for self- and other-reference has received considerable attention in recent decades, primarily through the lens of feminist inquiry (pioneered by Bodine 1975) and, more recently, queer perspectives (e.g., McLemore 2015; Zimman 2017; Bradley 2020; Konnelly and Cowper 2020). The pronoun they initially sparked debate due to its role as a singular gender-neutral pronoun, skillfully sidestepping gender assignment, as seen in examples like someone lost their keys (Balhorn 2009; Paterson 2014; LaScotte 2016; Loureiro-Porto 2020). However, its evolution expanded beyond gender neutrality to represent nonbinary identities (Bradley et al. 2019; Conrod 2019; Bradley 2020; Hekanaho 2020, 2024).

Recent research highlights the discomfort of nonbinary individuals, who diverge from the gender binary, grammatically expressed by he or she, resulting in intentional and unintentional misgendering (Simpson and Dewaele 2019: 105–106; Konnelly et al. 2024: 453–454). Responding to this, the groundwork laid by feminists for singular they made it the prime candidate to fill this void, leading to its recognition as the word of the year in 2019 by Merriam Webster (Harmon 2019).2 Simultaneously, new alternatives, termed neopronouns, like ze and xe, emerged to address this gap (Hegarty et al. 2018: 55), as illustrated in (1) and (2):

The plethora of emerging pronominal possibilities underscores the complexity of transforming English into a more inclusive language. Nonbinary individuals, recognizing the pivotal role of pronouns in defining their identities, emphasize the significance of being referred to by pronouns that align with their sense of self. Some scholars, such as Zimman (2017: 156), advocate for an egalitarian approach, proposing that the most inclusive method for personal pronoun reference is to inquire directly about individuals’ preferred pronouns. Conversely, some argue that certain LGBTQI+ individuals perceive gender pronouns as limiting in encapsulating their complex identities, leading to a call for the complete avoidance of gender-specific pronouns in reference to any individual (Dembroff and Wodak 2018: 372). These discussions illuminate the identity-building function of pronouns, emphasizing their role in intersubjective identity construction through discourse interaction (Bucholtz and Hall 2010; Hekanaho 2024).

In situations where individuals are not explicitly asked about their pronouns, they may choose to overtly state them, as observed in social networks like X (formerly Twitter), where users have at their disposal 160 characters to define their public profiles (known as bios), according to their own wishes.3 A cursory examination of random profiles reveals a diverse array of pronoun claims and combinations, including binary pronouns, nonbinary (NB) pronouns, and a blend of binary and NB pronouns, commonly referred to as rolling pronouns (e.g., they/he; LGBTQ Nation 2022). Moreover, online spaces like X and Tumblr have been found to favor the diffusion of new pronouns (King and Crowley 2024: 79–82). These social media have also served as battlegrounds for intense discussions surrounding the ideological implications of adopting NB pronouns, as the act of disclosing one’s pronouns has “politicized as belonging to the left in current US politics” (King and Crowley 2024: 82). Against this backdrop, this paper conducts an analysis of NB pronoun usage in X bios in US-based accounts, considering various intra- and extra-linguistic features, detailed in Section 3 below, with the overarching goal of answering the following research questions:

RQ1: Which NB pronouns are predominantly used in X bios?

RQ2: Do NB pronouns coexist with binary ones, and if so, what is the prevalence of each pronoun?

RQ3: Does the claiming of pronouns allow for inflectional morphology (i.e., are non-nominative forms listed)?

RQ4: Are there discernible differences, considering the ideological value of NB pronouns, between individuals residing in cities with a tradition of Republican governments and those in cities with a tradition of Democrat governments?

RQ5: Does the assertion of NB pronouns correlate with specific profiles, such as activism of any sort?

To achieve these objectives, the following sections of the paper unfold as follows: Section 2 outlines the theoretical background, Section 3 explains the methodology, Section 4 reveals the findings, and Section 5 offers a comprehensive discussion. The paper concludes with key insights and conclusions in Section 6.

2. Nonbinary pronouns in English

For over 150 years, English wordsmiths have attempted to establish a gender-neutral pronoun without success (Baron 2010: n.p.), in contrast with some languages that have recently embraced gender-inclusive language approaches and alternatives to binary pronouns have been established, such as hen in Swedish, which reflects a growing acknowledgment of gender diversity (Lindqvist et al. 2019). Despite the historical existence of non-conforming gender individuals, who have been marginalized and persecuted for centuries (Herdt 1996: 11), they have faced a persistent lack of visibility and recognition. This is reflected in language, where the absence of an established third person singular genderless pronoun leads to misgendering (i.e., an erroneous attribution of gender, McLemore 2014: 53; see also Hekanaho 2020: 197) for those who do not conform to the gender binary. In this scenario Sections 2.1 and 2.2 review the pronominal choices available for nonbinary individuals and their relative success in recent years.

2.1. NB they

Despite the widespread belief that singular they is a modern linguistic innovation, its usage was prevalent in written English even before the twentieth century, with the first recorded instances dating back to Old English (Bodine 1975: 131; Curzan 2003: 70–71; Laitinen 2024: 36–38). However, the proscription against using singular they due to a lack of number agreement with the singular antecedent became prominent with the advent of prescriptive usage guides in 1770 (HUGE-database, Hyper Usage Guide of English; Straaijer 2014). This prohibition persisted until the twenty-first century, as seen in Batko (2004: 118–122), who cautioned against using “everyone...their” in formal speech or writing, advocating awareness of alternatives that adhere to prescriptive rules.

Amidst this prescriptivist landscape, the feminist movement of the 1960s, particularly second-wave feminism, played a pivotal role in revitalizing the usage of singular they. This resurgence aimed to combat linguistic sexism, bringing singular they into debate and gaining acceptance for referring to antecedents of unknown or irrelevant gender (Balhorn 2009; Paterson 2011, 2014; LaScotte 2016). Consequently, the trajectory of singular they being used with singular antecedents dates back to medieval times, where genderless or unknown antecedents were commonly referred to by singular they and combined with he or she (see Baron 2018, for example). Grammarians of that era criticized both options, deeming the first inaccurate due to a lack of number agreement and the second as “clumsy and pedantic” (Bodine 1975: 170; Paterson 2014: 123).

The prescriptive pressure on the use of singular they persisted over time, earning it the moniker of an “old chestnut,” frequently cited in usage guides (Tieken-Boon van Ostade 2020: 26; 58 out of 77 guides in the HUGE-database mention this issue). Nevertheless, the social rejection of generic he in the late twentieth century, driven by the recognition that a pronoun cannot be simultaneously masculine and generic, led to a shift in perception. Singular they, along with the combination of he or she, came to be viewed as gender-inclusive and, consequently, the preferred choice among speakers (LaScotte 2016: 63).

This capacity to denote singular antecedents whose gender is unknown or irrelevant likely facilitated the recent adoption of they as a choice for referring to nonbinary individuals. This category encompasses those who may not conform to the gender binary, identify with none or both genders, or reject the notion of having a gender identity (Matsuno and Budge 2017: 116). While resistance persists, possibly due to the blurred lines between grammar and social meaning (Konnelly and Cowper 2020: 16), studies have demonstrated the viability of they as a NB pronoun (Parker 2017; Lund Eide 2018; Bradley 2019; Hekanaho 2020; among many others). Notably, nonbinary they, encompassing inflectional forms such as they, them, their, theirs, and themself, has gained official recognition from institutions such as the University of Vermont (Scelfo 2015: n.p.) and is listed as a NB pronoun in the 2019 edition of the Merriam-Webster Dictionary (Merriam-Webster 2019). It is essential to acknowledge, however, that they is not the exclusive contender for an established NB pronoun, as various alternatives have been proposed, as explored in Section 2.2.

2.2. Neopronouns

In addition to the emerging use of they as a NB pronoun, the linguistic landscape has seen the introduction of numerous newly coined pronouns in recent decades, collectively referred to as ‘neopronouns’. These innovative pronoun sets, still in the process of gaining widespread acceptance, are cataloged on reference sites like http://www.pronouns.org/. The existence of these neologisms could be considered to challenge the conventional belief that pronouns constitute a closed class (Huddleston and Pullum 2002: 425), and, although their success, unlike that of singular they, has been limited (Lund Eide 2018; Parker 2017, cited in Hekanaho 2020: 39; Bradley et al. 2019), this has not hindered speakers from engaging in continual linguistic innovation. Consequently, the list of neopronouns is extensive and subject to change over time. While acknowledging the absence of a comprehensive academic list, we present here a compilation of “artificial and proposed epicene pronouns” as found in Wikipedia as of 20 November 2023:

|

Firstly attested |

Nominative |

Accusative |

Dependent Genitive |

Independent genitive |

Reflexive |

|

thon |

1884 |

thon is laughing |

I called thon |

thons eyes gleam |

that is thons |

thon likes thonself |

|

e |

1890 |

e is laughing |

I called em |

es eyes gleam |

that is es |

e likes emself |

|

ae |

1920 |

ae is laughing |

I called aer |

aer eyes gleam |

that is aers |

ae likes aerself |

|

tey |

1971 |

tey is laughing |

I called tem |

ter eyes gleam |

that is ters |

tey likes temself |

|

xe |

1973 |

xe is laughing |

I called xem/xim |

xyr/xis eyes gleam |

that is xyrs/xis |

xe likes xemself/ximself |

|

te |

1974 |

te is laughing |

I called tir |

tes eyes gleam |

that is tes |

te likes tirself |

|

ey |

1975 |

ey is laughing |

I called em |

eir eyes gleam |

that is eirs |

ey likes emself |

|

per |

1979 |

per is laughing |

I called per |

per eyes gleam |

that is pers |

per likes perself |

|

ve |

1980 |

ve is laughing |

I called ver |

vis eyes gleam |

that is vis |

ve likes verself |

|

hu |

1982 |

hu is laughing |

I called hum |

hus eyes gleam |

that is hus |

hu likes humself |

|

e |

1983 |

e is laughing |

I called em |

eir eyes gleam |

that is eirs |

e likes emself |

|

ze, mer |

1997 |

ze is laughing |

I called mer |

zer eyes gleam |

that is zers |

ze likes zemself |

|

ze, hir |

1998 |

ze is laughing |

I called hir |

hir eyes gleam |

that is hirs |

ze likes hirself |

|

sie, hir |

2001 |

sie is laughing |

I called hir |

hir eyes gleam |

that is hirs |

sie likes hirself |

|

sey, seir, sem |

2013 |

sey is laughing |

I called sem |

seir eyes gleam |

that is seirs |

sey likes Sem self |

fae |

2020 | fae is laughing |

I called faer |

faer eyes gleam |

that is faers |

fae likes faerself |

Table 1: List of proposed neopronouns (adapted from Wikipedia 2023)4

The pronouns listed in Table 1 exhibit varying degrees of popularity, with some receiving more attention on authoritative websites like gendercensus.com (2022). Notably highlighted are the following: (1) e (e/em/eir/eirs/emself; known as ‘Spivak pronouns’);5 (2) ey (ey/em/eir/eirs/emself, known as ‘Elverson pronouns’);6 (3) ze (ze/hir/hir/hirs/hirself); (4) xe (xe/xem/xyr/xyrs/xemself); and (5) fae (fae/faer/faer/faers/faeself) (gendercensus 2022; see also Venkatraman 2020). These pronouns do not only differ in popularity but also in phonological weight: e and ey contain vocalic sounds resonant with she and they while xe and ze are sometimes pronounced as /zi:/ or /ksi:/ (Hekanaho 2020: 4).

Additionally, fae stands out as it can be considered a nounself pronoun, a category of new pronouns typically derived from specific words, often nouns associated with individuals’ identity. In the case of fae, it is claimed to originate from an Irish old form of the word fairy (Miltersen 2016: 42). Nounself pronouns constitute a distinct class, allowing any noun or word to function as a pronoun based on individual preference. Miltersen (2016: 42) identifies examples like onomatopoeias (tok, purr), proper names, and clipped versions of nouns such as bun/bun/buns/bunself (from bunny) and bi/bir/birs/birself (from bird). However, it is crucial to note that none of these neopronouns are considered to hold the same status as singular they (Hekanaho 2024: 140). Their prominence may result from the rarity of introducing new members to a grammatical paradigm, especially within the context of pronouns being perceived as a closed class resistant to change (Huddleston and Pullum 2002: 425).

Navigating the vast array of neopronouns in use within the nonbinary community poses a considerable challenge, as emphasized by Hakanen (2021: 12), who, while examining xe, ze, and zie in four extensive corpora, retrieved just over one hundred tokens (Hakanen 2021: 14). Given this difficulty, researchers often resort to surveys to elicit pronoun usage (e.g., Hekanaho 2020) or turn to online platforms like forums for data collection (e.g., Zimman 2019). Here, we propose an alternative avenue for exploration: social networks such as X, which have proven to be invaluable for investigating authentic language use in the digital sphere (e.g. Tyrkkö et al. 2021; Laitinen and Fatemi 2023; Louf et al. 2023, to name just a few). Although limited research has delved into NB pronoun usage on X, a few related studies have focused on pronoun self-disclosure. Some works reveal disparities and shared patterns among female, male, and nonbinary users (Thelwall et al. 2021), while others have gleaned insights into pronoun usage trends (Jiang et al. 2022; Tucker and Jones 2023).

These studies yield two primary conclusions: 1) a rising trend in the self-disclosure of gender pronouns on social networks in recent years and 2) the prevalence of she as a gender pronoun on X, both independently and in combination with others, such as she/they (Jiang et al. 2022; Tucker and Jones 2023). Furthermore, pronoun lists in profiles often intertwine with personal attitudes common among nonbinary X users, such as leftist affiliations, the acronym ACAB (i.e., All Cops Are Bastards), and identifications like queer, trans, and pansexual (Tucker and Jones 2023: 12). Our analysis below will shed more light on these aspects.

3. Methodology

Established in 2006, the social platform X, formerly known as Twitter, has evolved into a ubiquitous and influential platform, attracting a diverse user base, including both ordinary individuals and high-profile figures such as celebrities and politicians. With approximately 87 million monthly users in the United States (Semiocast 2023) and a reported usage rate of about 23 percent among U.S. adults (Pew Research 2022a). Thus, X has become deeply ingrained in the lives of a significant portion of the population, and this widespread impact positions X as a compelling and valuable tool for the scrutiny of human behavior.

X functions as a platform where users can articulate and exchange their ideas, fostering the creation of online conversational threads. Given its nature, X provides an ideal environment for investigating the spontaneous production and utilization of language, making it a common choice for linguistic studies (e.g., Zappavigna 2012; Friginal et al. 2018; Gonçalves et al. 2018; Clarke and Grieve 2019; Grieve et al. 2019; Page et al. 2022). The platform enables data collection through its Application Programming Interface (API) libraries (Campan et al. 2018: 3640). Additionally, analytics platforms like Followerwonk (Followerwonk 2022), which offers insights into X users, their followers, social authority, and various metrics, facilitate the extraction of valuable information.7 While Followerwonk might not be the most prevalent analytics platform online, scholars have utilized it across different fields of study, ranging from assessing the visibility of financial institutions providing microcredit in Ecuador (Espinoza-Loaiza et al. 2017) to exploring pharmaceutical and medical purposes (Styczynski et al. 2023). Its versatility in analyzing and extracting meaningful information makes it a valuable tool for collecting data for this study.

The data for this paper was sourced from X bios, which are short profiles containing personal information provided by users (this information may include hobbies, place of residence and also icons or emojis). Followerwonk was employed for data extraction and the search focused on potential NB pronouns, specifically the nominative forms listed in Table 1, including they and others. The search specifically targeted the nominative forms as they represent the unmarked form, which may or may not be accompanied by oblique forms in X bios (e.g., they/them, they/them/their).

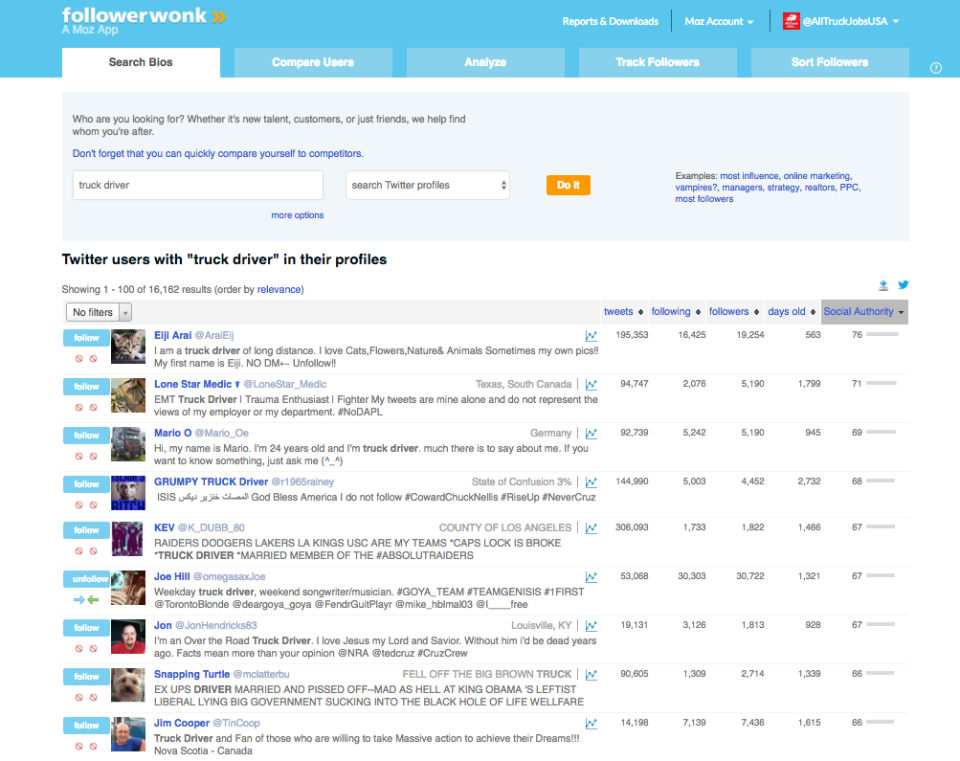

The platform’s default presentation of results was organized based on the number of followers for each account. However, the list could be sorted using various metrics, such as the number of tweets, following accounts, account age (measured in days), and social mentions, along with their impact, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Followerwonk results view

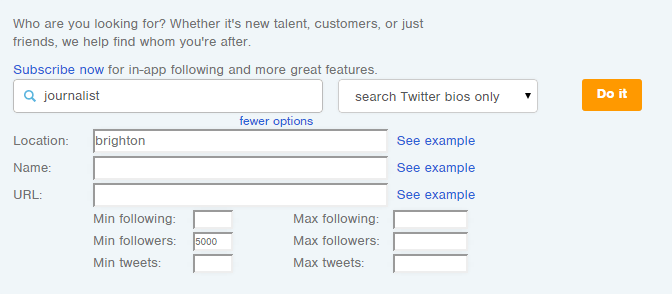

The advanced filters provided by Followerwonk offer the flexibility to set minimum and/or maximum thresholds for the number of followers, tweets, and following accounts (Figure 2). Notably, the sorting feature by location is a particularly valuable tool. Given that one of the objectives in the study is to examine the potential influence of dominant political views on the choice of NB pronouns in specific regions, we utilized this feature to identify locations with traditions of both Republican and Democrat governments. This information was based on the classification provided by Tausanovitch and Warshaw (2014). The rationale behind the selection of accounts from these particular locations stems from the aforementioned discovery by King and Crowley (2024: 82), who observed that NBs have played a significant role in shaping online political discussions. They are often perceived as aligning with left-wing ideological positions in the current landscape of US politics and are frequently targeted for ridicule by conservative users of platform X.

For the representation of territory with a tendency for liberal governments, New York was chosen as the focal city, because Followerwonk allowed us to conduct searches for each of its five boroughs, ensuring an adequate number of tokens for inclusion in our database. On the conservative side, multiple cities were selected. As these cities are not as populous as New York, their results were aggregated to achieve a balanced sample. The chosen cities were specifically identified as standing on the more conservative end of the political spectrum, including Colorado Springs, Fort Worth, Jacksonville, Oklahoma City, Omaha, and, for a larger city example, Miami.

Figure 2: Advanced filters in Followerwonk

Thus, each token included in our database was coded for the following extra-linguistic (1–2) and intra-linguistic variables (3–6):

A comprehensive search using Followerwonk identified a total of 12,282 accounts featuring NB pronouns within the explored territories. Specifically, there were 6,432 accounts in New York and 5,850 in the other cities (with a tradition of Republican governments). From each group, a sample of approximately 1,000 accounts was systematically chosen by adjusting the sorting options of the analytics platform. That is, since the 12,282 accounts could not be downloaded from Followerwonk for randomization, the only feasible approach to selecting a somewhat random sample was to sort the accounts based on factors such as account age and social authority. These factors were deemed to have a negligible impact on the use of NB pronouns and were thus not expected to introduce bias into the results. As the summarized results presented in Tables 2 and 3 show, a total of 1,980 accounts were analyzed.

|

Total number of accounts with NB pronouns |

Accounts selected |

|

Bronx |

776 |

151 |

|

Brooklyn |

3,502 |

418 |

|

Manhattan |

955 |

176 |

|

Queens |

1,038 |

230 |

Staten Island |

161 |

37 |

Total |

6,432 |

1,012 |

Table 2: Number of accounts collected from New York boroughs and the total number of results in Followerwonk

|

Total number of accounts with NB pronouns |

Accounts selected |

|

Colorado Springs |

446 |

122 |

|

Fort Worth |

717 |

131 |

|

Jacksonville |

811 |

122 |

|

Miami |

2,652 |

296 |

|

Oklahoma City |

606 |

131 |

|

Omaha |

618 |

166 |

|

Total |

5,850 |

968 |

Table 3: Number of accounts collected from US cities with a tradition of Republican governments and the total number of results in Followerwonk

4. Results

4.1. Monopronouns and rolling pronouns

X users have the option of self-definition through a single pronoun (e.g., they), termed ‘monopronoun’ use, or a combination of pronouns (e.g., they/he, she/they/xe), known as ‘rolling pronouns’ ––defined as “the use of multiple pronouns that can be used alternately or shift over time” (LGBTQ Nation 2022). Interestingly, rolling pronouns emerge as the prevailing trend in our dataset: as illustrated in Table 4, 65 percent of the scrutinized accounts in New York opt for multiple pronouns to articulate their gender identity, while 35 percent identify as monopronoun users. This statistically significant difference8 also holds for the other cities (65.6% of accounts exhibiting rolling pronouns vs. 34.4% of accounts showing monopronouns), suggesting a consistent pattern of pronoun usage.

|

New York accounts |

Other cities accounts |

Total |

|

Monopronouns users |

354 (35%) |

333 (34.4%) |

687 (34.7%) |

|

Rolling pronouns users |

658 (65%) |

635 (65.6%) |

1,293 (65.3%) |

Total |

1,012 |

968 |

1,980 |

Monopronoun and rolling pronoun users by community

The choice between a monopronoun and rolling pronouns significantly impacts the prevalence of inflectional forms other than the nominative in our dataset. Notably, monopronouns are frequently accompanied by non-nominative forms (98%),9 while rolling pronouns exhibit a lower proportion in this regard (90%), as illustrated in Table 5. This significant10 contrast between monopronouns and rolling pronouns can be attributed, in part, to the character limit (160) imposed on bios in X. Users employing rolling pronouns often prioritize conciseness due to character constraints, limiting the inclusion of additional inflectional forms in favor of other aspects of their personal profile. Nevertheless, ten percent of rolling pronoun users do include additional forms, as exemplified by constructions such as (i) he/him they/them she/her or (ii) they/them xe/xem. In contrast, monopronoun users predominantly opt for the nominative/accusative form, potentially reflecting a formulaic expression signaling the use of pronouns for gender identity purposes rather than as components of a broader linguistic structure. In essence, constructions like they/them, ze/zim/zer have become conventional ways of conveying one’s preferred pronouns (pronouns.org 2023).

|

Only nominative form |

Other inflectional forms |

Total |

|

Monopronouns users |

14 (2%) |

673 (98%) |

687 |

|

Rolling pronouns users |

1,164 (90%) |

129 (10%) |

1,293 |

Total |

1,178 (59.5%) |

802 (40.5%) |

1,980 |

Table 5: Presence of inflectional forms other than the nominative with monopronouns and rolling pronouns

An important finding in our analysis is that monopronoun users overwhelmingly favor singular they (Table 6). Specifically, only 21 accounts opt for a single neopronoun, with nine choosing ze, nine selecting xe, and three opting for ey ––each accompanied by distinct non-nominative forms. All other neopronouns examined in this study are found within rolling pronouns, predominantly led by they (49%). Following this are she (29.5%), he (20.4%), and neopronouns collectively, constituting a mere 1.1% of all accounts with rolling pronouns. Notably, there are minimal discrepancies between territories, with they being more frequent in New York than in the other cities analyzed (51.7% vs. 46.3%). Conversely, she exhibits a higher frequency in other cities (32.1% vs. 27%), as shown in Table 6:

First chosen pronoun |

New York |

Other cities |

Total |

|

They |

523 (51.7%) |

448 (46.3%) |

971 (49%) |

|

He |

205 (20.3%) |

199 (20.6%) |

404 (20.4%) |

|

She |

273 (27%) |

311 (32.1%) |

584 (29.5%) |

|

Neopronouns |

11 (1%) |

10 (1%) |

21 (1.1%) |

Total |

1,012 |

968 |

1,980 |

Table 6: First pronoun chosen by X users in rolling pronouns: New York vs. other cities

The incorporation of gendered pronouns alongside NB pronouns is a prevalent phenomenon in our dataset, since a total of 1,254 accounts feature either he, she, or a combination of both, as illustrated in Table 7:11

|

|

Raw Frequency |

Percentage |

|

He |

482 |

38.4% |

|

She |

712 |

56.8% |

|

He and she |

60 |

4.8% |

Total |

1,254 |

100% |

Table 7: Nonbinary users in our dataset with at least one gendered pronoun

Furthermore, our analysis of X accounts reveals that when users opt for gendered pronouns alongside NB pronouns, they predominantly choose he or she as their first pronoun before specifying their NB pronoun. Table 8 illustrates this trend, indicating that 74.3 percent of users prefer he (e.g., he/they), mirroring the 75.5 percent of users who opt for she (e.g., she/they).

|

Bios with he |

Bios with she |

TOTAL |

|

They |

403 (74.3%) |

27 (3.5%) |

430 |

|

Nounself pronoun |

14 (2.6%) |

583 (75.5%) |

597 |

|

Xe |

123 (22.7%) |

161 (20.9%) |

284 |

|

It |

2 (0.4%) |

1 (0.1%) |

3 |

Total |

542 |

772 |

1,314 |

Table 8: First pronoun in set of rolling pronouns that include (binary) gendered he and she

Table 8 also highlights the infrequent occurrence of neopronouns within rolling pronouns that include gendered he or she. However, a comprehensive examination of the entire set of rolling pronoun options in the analyzed accounts reveals that neopronouns are not uncommonly selected as second or subsequent options by X users: For instance, examples such as 1) they (ey/em/eir), 2) she/he/they/xe/xim, and the most elaborate instance in our dataset, 3) he/ him /his /she /her /sher /hershey’s /zhe/zher /zir/xyr/they/them/thems/they’re/their/there/thon/fae/I/me/you/your/you’re/us/y’all/we/ wumbo/it/that/this/thit/pronoun. The specific frequency of neopronouns in comparison to they is detailed in Section 4.2 below.

4.2. Type of NB pronoun: They and neopronouns

Table 9 shows the frequency of all NB pronouns found. The data clearly shows the prevalence of they (95% of all cases). As mentioned, these pronouns could appear in any position in the users’ bios, since neopronouns hardly ever appear as monopronouns and, for that reason, the total number of tokens surpasses the number of accounts analyzed.

|

New York |

Other cities |

Total |

|

They |

982 |

952 |

1,934 (95.%) |

|

Nounself pronoun |

18 |

5 |

23 (1.1%) |

|

Xe |

10 |

10 |

20 (1%) |

|

It |

9 |

8 |

17 (0.9%) |

|

Ze |

11 |

2 |

13 (0.6%) |

|

Foreign pronouns |

8 |

4 |

12 (0.6%) |

|

Fae |

6 |

1 |

7 (0.3%) |

|

Any (pronoun) |

2 |

3 |

5 (0.3%) |

|

Ey |

2 |

2 |

4 (0.2%) |

Total |

1,048 |

987 |

2,035 |

Table 9: Distribution of NB pronouns in the dataset

In addition to reinforcing the nonbinary status of they, Table 9 also arranges the neopronouns from Table 1 as follows: nounself pronouns exhibit the highest prevalence (23 tokens in total, e.g., pup or neigh), followed by xe (20 tokens), ze (13), fae (7), and ey (4). Furthermore, Table 1 includes other pronominal forms discovered incidentally (as a second or later option in rolling pronouns). These include the pronoun it (17), foreign pronouns such as elle (from Spanish)12 or sie (from German) (12), as well as any, a concise form standing for any pronoun (5), suggesting a clear flexibility in the users’ choice of pronouns. The presence of nounself pronouns is noteworthy, considering their diverse nature, with almost none repeated (e.g., thude, neon, or bruh; exemplified in he/they/neigh/bruh/skull/neon), except for fae, which occurs several times and could be included in this category. The NB pronoun it also appears with relative frequency, despite assertions that it may be dehumanizing and perilous (Norris and Welch 2020: 9). Some users express comfort with being referred to with this pronoun alongside other NB pronouns (e.g., they/it; they/it/ze; or xe/they they/jze/it). Additionally, X users have incorporated NB pronouns from other languages, such as elle, proposed in Spanish, and sie, representing the third person singular feminine and also the plural in German (e.g., he/they El/Elle; they/sie/them), serving as anecdotal evidence of the multilingual nature of the social network, despite its overwhelming English-speaking majority (Grandjean 2016: 6). Regarding differences between political territories, due to the overall small number of neopronouns, no statistical test can be applied, and the distinctions between territories traditionally ruled by Democrats and Republicans do not seem to be relevant.

4.3. Keywords in bios

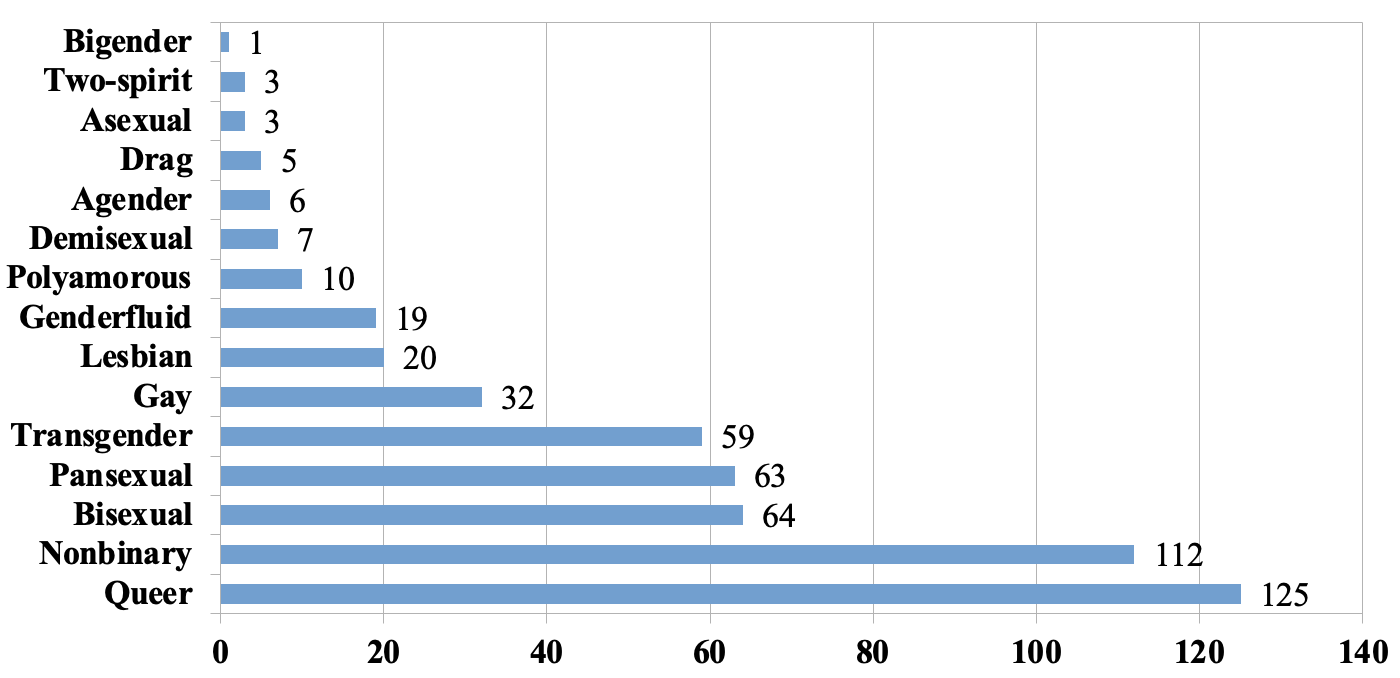

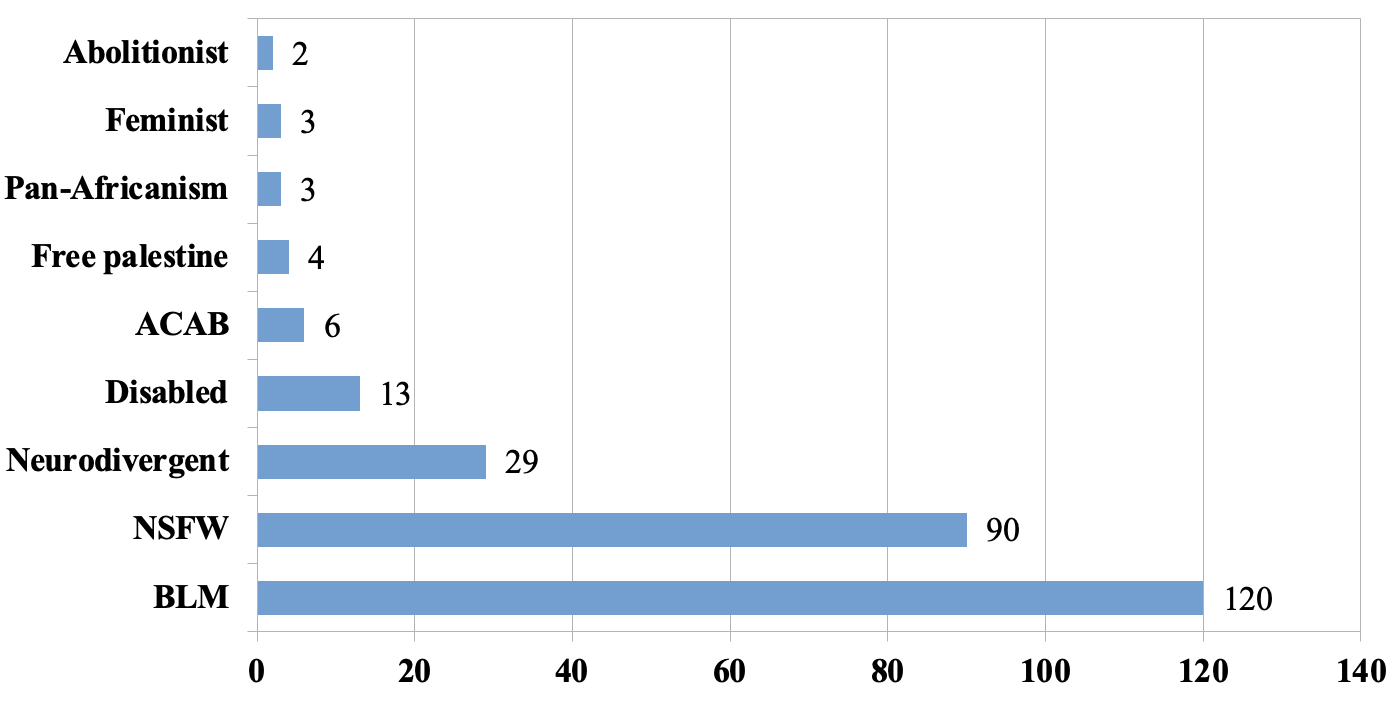

The final result concerning the variables in our dataset (outlined in Section 3 above) pertains to the presence of lexical keywords in X bios related to gender identity, sexuality (e.g., queer, trans, bisexual), or various forms of activism related to different causes (e.g., climate change, Black Lives Matter, autism). After the manual examination of the 1,980 accounts analyzed, the findings indicate that 26.7 percent of X accounts (n= 529) incorporate keywords reflecting their sexual or gender identity (as depicted in Figure 3), whereas the inclusion of personal and political keywords is slightly lower, accounting for 13.6 percent (n= 270, as illustrated in Figure 4).

Figure 3: Keywords related to gender identity or sexuality that accompany NB pronouns in our dataset

Figure 3 provides an overview of the frequency of keywords associated with gender identity and sexuality that co-occur with NB pronouns in our dataset. The observed keywords can be categorized into four primary blocks. Firstly, queer emerges as the most prevalent term in X profiles, appearing 125 times, closely followed by nonbinary with 112 instances. In the second block, the triad of bisexual (64), pansexual (63), and transgender (59) takes precedence. The third block comprises terms such as gay (32), lesbian (20), and genderfluid (19). Lastly, we encounter less frequent terms like polyamorous (10), demisexual (7), agender (6), drag (5), asexual (3), two-spirit (3), a characteristic term within the Native American community and bigender (1).

Figure 4 highlights the prevalence of additional keywords in our dataset that offer insights into users’ profiles. At the forefront is the acronym BLM, which stands for Black Lives Matter, appearing in 120 accounts. Following closely is another acronym, NSFW (Not Suitable/Safe for Work), present in 90 accounts, often associated with explicit or inappropriate material rather than specific political affiliations. In the third and fourth positions, we encounter terms that bring visibility to minority groups: 9 instances of neurodivergent and 13 of disabled. The list continues with politically charged labels, including ACAB (All Cops Are Bastards) in six accounts, Free Palestine in four, and three instances each of Pan-Africanism and Feminist, and two of Abolitionist. The significance of these figures lies more in their qualitative implications than their quantitative representation. As demonstrated in prior studies (e.g., Tucker and Jones 2021), data hint at a connection between actively articulating one’s nonbinary identity and expressing overt support for specific social causes.

Figure 4: Keywords related to some kind of activism on X that accompany NB pronouns in our dataset

5. Discussion

This paper has studied the presence of NB pronouns in X profiles, with the aim of determining the factors that might condition the variation among the myriad of NB pronouns available as of 2023 (see Table 1). One such factor was considered to be the place of residence of X users, and for that reason data were collected (using the extinct X analytics platform Followerwonk) based on geographical or political factors. Two samples were taken from a city traditionally ruled by Democrats, namely New York, and several cities traditionally ruled by Republicans. The results do not conclusively establish a correlation between political affiliations of a territory and pronoun choices by the citizens. Thus, our results show no significant differences between users in both kinds of territory regarding aspects such as the frequency of monopronouns and rolling pronouns (Table 4), the pronoun that occupies first position in rolling pronouns (Table 6), or the particular frequency of they and the neopronouns (Table 9). This can very well be interpreted as the result of the global character of online communities, which tend to behave alike regardless of their particular geographical location, as has been previously found for K-pop communities (Malik and Haidar 2020: 11). Thus, although notable differences have been found in previous literature between the use of X by Republicans (17%) and Democrats (32%) (Pew Research 2022b), one cannot conclude either that i) all X users living in a city ruled by one party follow their political views, or that ii) the main political view of a geographical territory is the only influence on netizens in an increasingly globalized word. Therefore, it looks as if the once claimed true democratic nature of social networks (e.g., Orr et al. 2009), where everyone had a voice and social differences were erased is still at work among NB individuals on X.

The unequivocal dominance of the pronoun they emerges as a defining characteristic within the dataset. This overwhelming usage (1,953 out of 1,980 accounts) supports the argument that they is the most widely accepted NB pronoun, overshadowing neopronouns in popularity (also noted by Hekanaho 2020: 222). The closed nature of the pronoun system, where new forms like neopronouns struggle for acceptance, contrasts with the smoother transition provided by they, which despite having been proscribed in usage guides for over two centuries has found its way into standard varieties of English very much thanks to the non-sexist language reform initiated by second-wave feminism in the 1960s (Paterson 2020: 261–264). Thus, in the battle for non-sexist language feminists defended the use of singular they or combined he or she and both were consistently neglected by the gate-keepers of the language, on the basis that the former violates number agreement with its antecedent and the latter leads to a cumbersome style. In the twenty-first century, however, and among nonbinary individuals, the otherwise proscribed they is considered as “more reasonable” than the neopronouns (Hekanaho 2020: 222), as it is seen as more familiar and easier to educate family and friends on the reference towards nonbinary individuals (McGlashan and Fitzpatrick 2018: 12; Cordoba 2020: 58). Among neopronouns, according to our results, nounself pronouns head the list, on most occasions with nonce forms such as thude, neon or bruh, and they are followed by xe, it, ze, foreign pronouns, fae, any and, finally ey (see Table 9). The multiplicity of options available reveals i) that linguistic creativity has no boundaries, ii) that gender identity is very complex and multifaceted and individuals enjoy the possibility of choosing how they want to be referred to, and iii) that we may be in the midst of a case of language variation that will end up in the survival of one or several pronominal forms if such forms manage to seamlessly integrate into the linguistic paradigm. The higher their integration, the higher their accessibility for individuals outside the LGBTQI+ community, and among these they is said to be clear winner (Hekanaho 2020: 222), as our results support.

Despite this preference for they, we have also seen that a vast majority of X users define their identity by rolling pronouns, highlighting a preference for multiple pronouns over a single one. This term encompasses individuals who may alter their pronouns based on context or employ them regularly, indicating the fluidity of gender identity expression. The prevalence of rolling pronouns users may be attributed to factors like gender fluidity or the comfort nonbinary individuals feel using multiple pronouns during transitional phases (McGlashan and Fitzpatrick 2018: 9; Jiang et al. 2022). This is in fact supported by the fact that gendered pronouns exhibit a much higher frequency than expected (1,254 tokens in our dataset include either he or she in the list of pronouns of choice alongside other NB pronouns). However, we acknowledge that more qualitative investigation will be necessary to understand specific preferences in different contexts.

The analysis of rolling pronouns in X bios also revealed that inflectional forms other than the nominative tend to be absent (90% of the times, as seen in Table 5), while it is overwhelmingly present in monopronouns (98%). A potential explanation for the absence of oblique forms is the 160-character limit in X bios, but that does not explain its practically total presence in the case of monopronouns. In that case, we believe that the near-formulaic nature of the combination of nominate and accusative or genitive forms (e.g., they/them or they/them/their) constitutes a well-established linguistic chunk associated with the communication of gender identity.

As expected, the use of NB pronouns correlates largely with the presence of lexical terms related to gender and sexuality (Figure 3). Likewise, political ideologies and personal beliefs find expression on X, with left-wing ideologies prominently represented through keywords like BLM and ACAB (as already mentioned by Tucker and Jones 2023: 11). Our results list these and other politically oriented key terms (Figure 4) and also highlights the inclusion of NSFW as a prevalent keyword, which suggests a shift in online discourse, reflecting a growing inclusion of explicit content. Additionally, the emergence of keywords related to neurodivergence, such as autistic, aligns with the notion that certain nonbinary individuals may have a higher likelihood of being neurodivergent (McClurg 2023). This intersectionality hints at the complex interplay between gender identity and neurodiversity, urging further exploration within this intersection.

6. Conclusions

Transforming English into a more inclusive language is a challenging task and nonbinary individuals find on social networks, such as X, a way of expressing their identity freely. A key strategy for claiming identity involves the selection of personal pronouns. This paper has contributed to the ongoing discourse on NB pronouns by scrutinizing the pronouns chosen by users in 1,980 X accounts. The analysis aimed to uncover sociolinguistic patterns among the myriad of NB pronouns available, considering both extra-linguistic and intra-linguistic variables. In the examination of extra-linguistic variables, we have scrutinized the role played by municipal political government, reflecting the overall Democrat or Republican majority in various cities. Additionally, we assessed the potential activism of users by considering the presence of lexical keywords related to specific political issues. Within intra-linguistic variables, we examined firstly the order of pronouns, particularly in cases where more than one pronoun was chosen ––a prevalent occurrence in 65.3 percent of all cases, exemplified by rolling pronouns like they/xe. Secondly, we investigated the presence of inflectional forms beyond the nominative, such as they/them. Finally, the analysis also encompassed the presence of binary gendered pronouns, he and/or she, and the selection of lexical gender-related vocabulary within the X bio.

Through a meticulous examination of 1,980 X accounts, a distinct pattern emerged, overwhelmingly favoring the use of they among nonbinary users, evident in 1,953 instances (RQ1). This prevalence constitutes a case of (quasi-)standardization, challenging traditional proscriptions that survived until the twenty-first century (as an example, Batko’s 2004 usage guide still considers singular they a mistake when used with singular antecedents such as everyone). Beyond they, the dataset reveals the presence of other NB pronouns, frequently embedded in rolling pronouns. Nounself pronouns (Miltersen 2016), including thude, neon, and bruh, take the lead, followed closely by xe, it, ze, foreign pronouns, fae, any, and, ultimately, ey. Despite this diversity, all neopronouns collectively constitute only five percent of the entire set of NB pronouns in our dataset (Table 9). This observation suggests that the path paved by feminists in the non-sexist language reform has predominantly favored the acceptance of singular they, a usage that has persisted since medieval times.

The prevalence of they, however, coexists with the utilization of (binary) gendered pronouns (he and/or she), collectively appearing on 1,254 occasions (RQ2) within the context of rolling pronouns. This co-occurrence suggests a transitional phase for some individuals, as tentatively interpreted in line with McGlashan and Fitzpatrick (2018: 9) and Jiang et al. (2022).

The distinction between rolling pronouns and monopronouns significantly influences the presence of inflectional forms beyond the nominative (RQ3). While rolling pronouns predominantly manifest in the nominative form in 90 percent of instances, monopronouns exhibit an oblique form 98 percent of the times. This discrepancy is interpreted as a consequence of the formulaic nature of the nominative/oblique form of the pronoun, showcasing a conventionalized way of expressing one’s identity.

The political traditions of the cities where the X users reside (RQ4) has proven to be a non-significant factor in explaining the variation among NB pronouns. This uniform behavior exhibited by X users, irrespective of territorial factors, is attributed to the difference-erasing role of social networks. Profiles tend to conform more with the globalized nature of the internet than with specific geographical neighbors.

Addressing RQ5, our work reveals a remarkable correlation between the presence of NB pronouns and lexical keywords related to gender and sexuality on one hand, and political activism on the other. This correlation suggests that individuals on the social network utilize NB pronouns as part of a broader strategy for activist purposes, aligning with a trend to increase visibility and assert their rights as citizens.

In conclusion, the comprehensive analysis of NB pronoun usage on X offers valuable insights into the intricate connections between language, identity, and online dynamics. The dominance of they, the emergence of rolling pronouns users, and the challenges faced by neopronouns underscore the nuanced nature of gender identity expression in digital spaces. Our study is subject to certain limitations, including the restricted sample size of X accounts examined, the potential bias introduced by Followerwonk, and the focus solely on US-based accounts. Consequently, it is important to refrain from interpreting our findings as indicative of the global English-speaking community’s perspectives on X. Instead, they should be regarded as a gateway to further exploration of online spaces. Thus, other avenues should be explored, like the intersectionality of gender identity, political expressions, and linguistic choices, providing a rich foundation for future research within the LGBTQI+ community.

References

Balhorn, Mark. 2009. The epicene pronoun in contemporary newspaper prose. American Speech 84/4: 391–413.

Baron, Dennis. 2010. The Gender-Neutral Pronoun: 150 Years Later, still an Epic Fail. OUPblog. https://blog.oup.com/2010/08/gender-neutral-pronoun/ (25 June, 2023.)

Baron, Dennis. 2018. A Brief History of Singular ‘They’. The Web of Language. Dennis Baron’s Go-to Site for Language and Technology in the News. https://www.oed.com/discover/a-brief-history-of-singular-they/?tl=true (27 April, 2024.)

Baron, Dennis. 2020. What’s Your Pronoun? Beyond He and She. London: Liveright.

Batko, Ann. 2004. When Bad Grammar Happens to Good People. How to Avoid Common Errors in English. Franklin Lakes: Career Press.

Bodine, Ann. 1975. Androcentrism in prescriptive grammar: Singular ‘they’, sex-indefinite ‘he’, and ‘he or she’. Language in Society 4: 129–146.

Bradley, Evan. 2020. The influence of linguistic and social attitudes on grammaticality judgments of singular ‘they’. Language Sciences 78: 1–11.

Bradley, Evan, Julia Salkind, Ally Moore and Sofi Teitsort. 2019. Singular ‘they’ and novel pronouns: Gender-neutral, nonbinary, or both? Proceedings of the Linguistic Society of America 4/36: 1–7.

Bucholtz, Mary and Kira Hall. 2010. Locating identity in language. In Carmen Llamas and Dominic James Landon Watt eds. Language and Identities. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 18–28.

Campan, Alina, Tobel Atnafu, Traian Marius Truta and Joseph Nolan. 2018. Is data collection through Twitter reaming API useful for academic research? IEEE International Conference on Big Data: 3638–3643. https://doi.org/10.1109/BigData.2018.8621898.

Clarke, Isobelle and Jack Grieve. 2019. Stylistic variation on the Donald Trump Twitter account: A linguistic analysis of tweets posted between 2009 and 2018. PLoS ONE 14/9: e0222062. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222062.

Conrod, Kirby. 2019. Pronouns Raising and Emerging. Washington: University of Washington doctoral dissertation.

Cordoba, Sebastian. 2020. Exploring Non-Binary Genders: Language and Identity. Leicester: De Montfort University dissertation.

Curzan, Anne. 2003. Gender Shifts in the History of English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dembroff, Robin and Daniel Wodak. 2018. He/she/they/ze. Ergo: An Open Access Journal of Philosophy 5/14: 371–406.

Espinoza-Loaiza, Viviana, Rosario Puertas, Valentin Martínez, Aurora Samaniego-Namicela and Eulalia-Elizabeth Salas-Tenesaca. 2017. Visibility and impact of the microcredit and the digital social media: A case study of financial institutions in Ecuador. In Francisco Campos ed. Media and Metamedia Management. Switzerland: Springer, 413–418.

Followerwonk. 2022. Tools for Twitter Analytics, Bio Search and More. https://followerwonk.com/search-bio.html (30 December, 2022.)

Friginal, Eric, Oksana Waugh and Ashley Titak. 2018. Linguistic variation in Facebook and Twitter posts. In Eric Friginal ed. Studies in Corpus-Based Sociolinguistics. New York: Routledge, 342–363.

Gender Census. 2022. Gender Census 2022: Worldwide Report. https://www.gendercensus.com/results/2022-worldwide/#pronouns (25 June, 2023.)

Gonçalves, Bruno, Lucía Loureiro-Porto, José J. Ramasco and David Sánchez. 2018. Mapping the americanization of English in space and time. PLoS ONE 13/5: e0197741. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197741

Grandjean, Martin. 2016. A social network analysis of Twitter: Mapping the digital humanities community. Cogent: Arts & Humanities 3. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2016.1171458.

Grieve, Jack, Chris Montgomery, Andrea Nini, Akira Murakami and Diansheng Guo. 2019. Mapping lexical dialect variation in British English using Twitter. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence 2/11. https://doi.org/10.3389/frai.2019.00011.

Hakanen, Lotta. 2021. “Let xir do Whatever xe wants”: A Corpus Study on Neopronouns ze, xie and zie. Tampere: Tampere University Bachelor’s Thesis.

Harmon, Amy. 2019. ‘They’ is the Word of the Year, Merriam-Webster Says, Noting its Singular Rise. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/10/us/merriam-webster-they-word-year.html#:~:text=Merriam%2DWebster %20announced%20the%20pronoun,whose%20gender%20identity%20is%20nonbinary (1 July, 2023.)

Hegarty, Peter, Y. Gavriel Ansara and Meg-John Barker. 2018. Nonbinary gender identities. In Nancy K. Dess, Jeanne Marecek and Leslie C. Bell eds. Gender, Sex, and Sexualities: Psychological Perspectives. New York: Oxford University Press: 53–76.

Hekanaho, Laura. 2020. Generic and Nonbinary Pronouns: Usage, Acceptability and Attitudes. Helsinki: University of Helsinki dissertation.

Hekanaho, Laura. 2024. The communicative functions of 3rd person singular pronouns: Cisgender and transgender perspectives. In Minna Nevala and Minna Palander-Collin eds. Self- and Other-Reference in Social Contexts. From Global to Local Discourses. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 138–165.

Herdt, Gilbert. 1996. Third Sex, Third Gender: Beyond Sexual Dimorphism in Culture and History. Brooklyn: Zone Books.

Huddleston, Rodney and Geoffrey K. Pullum. 2002. The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ingram, David. 2023. Elon Musk’s New Twitter Pronoun Rule Invites Bullying, LGBTQ Groups Say. NBC News. 2 June 2023. https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/tech-news/elon-musks-new-twitter-pronoun-rule-invites-bullying-lgbtq-groups-say-rcna87336 (30 September, 2023.)

Jiang, Julie, Emily I. Chen, Luca Luceri, Goran Muric, Francesco Pierri, Ho-Chun Herbert Chang, and Emilio Ferrara. 2022. What are your pronouns? Examining gender pronoun usage on Twitter. ArXiv (Cornell University). https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2207.10894.

King, Brian W. and Archie Crowley. 2024. The future of pronouns in the online/offline nexus. In Laura Louise Paterson ed., 74–86.

Konnelly, Lex and Elizabeth Cowper. 2020. Gender diversity and morphosyntax: An account of singular they. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 5/1: 40. https://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.1000.

Konnelly, Lex, Kirby Conrod and Evan D. Bradley. 2024. Non-binary singular they. In Laura Louise Paterson ed., 450–464.

Laitinen, Mikko. 2024. A history of personal pronouns in Standard English. In Laura Louise Paterson ed., 29–43.

Laitinen, Mikko and Masoud Fatemi. 2023. Data-intensive sociolinguistics using social media. Annales Academiae Scientiarum Fennicae 2023/2: 38–61.

LaScotte, Darren K. 2016. Singular they: An empirical study of generic pronoun use. American Speech 91/1: 62–80.

LGBTQ Nation. 2022. Why some People Use She/They & He/They Pronouns. LGBTQ Nation. https://www.lgbtqnation.com/2022/05/people-use-pronouns/ (25 June, 2023.)

Lindqvist, Anna, Emma Aurora Renström and Marie Gustafsson Sendén. 2019. Reducing a male bias in language? Establishing the efficiency of three gender-fair language strategies. Sex Roles 81: 109–117.

López, Ártemis. 2019. Tú, yo, elle y el lenguaje no binario. La Linterna del Traductor 19: 142–150.

Louf, Thomas, Bruno Gonçalves, José J. Ramasco, David Sánchez and Jack Grieve. 2023. American cultural regions mapped through the lexical analysis of social media. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01611-3

Loureiro-Porto, Lucía. 2020. (Un)democratic epicene pronouns in Asian Englishes: A register approach. Journal of English Linguistics 48/3: 282–313.

Lund Eide, Mari. 2018. Shaping the Discourse of Gender-Neutral Pronouns in English: A Study of Attitudes and Use in Australia. Bergen: University of Bergen Master’s Thesis.

Malik, Zunera and Sham Haidar. 2020. Online community development through social interaction – K-pop stan Twitter as a community of practice. Interactive Learning Environments 31/2: 1–19.

Matsuno, Emmie and Stephanie L. Budge. 2017. Non-binary/genderqueer identities: A critical review of the literature. Current Sexual Health Reports 9: 116–120.

McClurg, Lesley. 2023. Transgender and Nonbinary People Are up to Six Times More Likely to Have Autism. NPR Hour Program Stream. https://www.npr.org/2023/01/15/1149318664/transgender-and-non-binary-people-are-up-to-six-times-more-likely-to-have-autism (26 June, 2023.)

McEnery, Tony, Richard Xiao and Yukio Tono. 2006. Corpus-Based Language Studies: An Advanced Resource Book. London: Routledge.

McGlashan, Hayley and Katie Fitzpatrick. 2018. I use any pronouns, and I’m questioning everything else: Transgender youth and the issue of gender pronouns. Sex Education 18: 239–252.

McLemore, Kevin. 2015. Experiences with misgendering: Identity misclassification of transgender spectrum individuals. Self and Identity 14/1: 51–74..

Merriam-Webster. 2019. A Note on the Nonbinary ‘They’. Merriam-Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/words-at-play/nonbinary-they-is-in-the-dictionary (20 November, 2023.)

Miltersen, Ehm Hjorth. 2016. Nounself pronouns: 3rd person personal pronouns as identity expression. Journal of Language Works 1/1: 37–62.

Norris, Marcos and Andrew Welch. 2020. Gender pronoun use in the university classroom: A post-humanist perspective. Transformation in Higher Education 5/0: a79. https://doi.org/10.4102/the.v5i0.79.

Orr, Emily S., Mia Sisic, Craig Ross, Mary G. Simmering, Jaime M. Arseneault and R. Robert Orr. 2009. The influence of shyness on the use of Facebook in an undergraduate sample. CyberPsychology & Behavior 12/3: 337–340.

Page, Ruth, David Barton, Carmen Lee, Johann Wolfgang Unger and Michele Zappavigna. 2022, Researching Language and Social Media. London: Routledge.

Parker, Linden. 2017. An Exploration of Use of and Attitudes towards Gender-Neutral Pronouns among the Non-Binary, Transgender and LGBT+ Communities in the United Kingdom. Colchester: University of Essex Master’s Thesis.

Paterson, Laura Louise. 2011. Epicene pronouns in UK national newspapers: A diachronic study. ICAME Journal 35: 171–184.

Paterson, Laura Louise. 2014. British Pronoun Use, Prescription, and Processing. Linguistic and Social Influences Affecting “they” and “he.” Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Paterson, Laura Louise. 2020. Non-sexist language policy and the rise (and fall?) of combined pronouns in British and American written English. Journal of English Linguistics 48/3: 258–281.

Paterson, Laura Louise ed. 2024. The Routledge Handbook of Pronouns. New York: Routledge.

Pew Research. 2022a. Social Media and News Fact Sheet. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/fact-sheet/social-media-and-news-fact-sheet/ (21 June, 2023.)

Pew Research. 2022b. 10 Facts about Americans and Twitter. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2022/05/05/10-facts-about-americans-and-twitter/ (7 June, 2023.)

Pronouns.org. 2023. Resources on Personal Pronouns. https://pronouns.org/ (20 November, 2023.)

Pronouns.page. 2024. List or Popular Pronouns.

https://en.pronouns.page/pronouns/#google_vignette (27 April, 2024.)

Pronouny. 2016–2020. Public Pronoun List. https://pronouny.xyz/pronouns/list/public (27 April, 2024.)

RAE (Real Academia de la Lengua Española). 2023. Los Sinónimos y Antónimos se Incorporan al «Diccionario de la Lengua Española» en su Actualización 23.7. https://www.rae.es/noticia/los-sinonimos-y-antonimos-se-incorporan-al-diccionario-de-la-lengua-espanola-en-su (28 November, 2023.)

Scelfo, Julie. 2015. A University Recognizes a Third Gender: Neutral. New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/08/education/edlife/a-university-recognizes-a-third-gender-neutral.html (8 June, 2023.)

Semiocast. 2023. Number of Twitter Users by Country. Semiocast. https://semiocast.com/number-of-twitter-users-by-country/ (21 June, 2023.)

Simpson, Lauren and Jean-Marc Dewaele. 2019. Self-misgendering among multilingual transgender speakers. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 256: 103–128.

Stormbom, Charlotte. 2024. Epicene pronouns new and old. In Laura Louise Paterson ed., 411–420.

Straaijer, Robin. 2014. Hyper Usage Guide of English (HUGE-database). Leiden: Leiden University.

Styczynski, Tomasz, Jagoda Sadlok and Jan Styczynski. 2023. Hematology on Twitter. Acta Haematologica Polonica 54/1: 6–10.

Tausanovitch, Chris and Christopher Warshaw. 2014. Representation in Municipal Goverment. American Political Science Review 108/3: 605–641.

Thelwall, Mike, Saheeda Thelwall and Ruth Fairclough. 2021. Male, female, and nonbinary differences in UK Twitter self-descriptions: A fine-grained systematic exploration. Journal of Data and Information Science 6/2: 1–27.

Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Ingrid. 2020. Describing Prescriptivism. Usage Guides and Usage Problems in British and American English. London: Routledge.

Tyrkkö, Jukka, Magnus Levin and Mikko Laitinen. Actually in Nordic tweets. World Englishes 40/4: 631–649.

Tucker, Liam and Jason J. Jones. 2023. Pronoun lists in profile bios display increased prevalence, systematic co-presence with other keywords and network tie clustering among US Twitter users 2015–2022. Journal of Quantitative Description: Digital Media 3. https://doi.org/10.51685/jqd.2023.003

Venkatraman, Sakshi. 2020. Beyond ‘He’ and ‘She’: 1 in 4 LGBTQ Youths Use Nonbinary Pronouns, Survey Finds. NBC News. 30 July 2020. https://www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/beyond-he-she-1-4-lgbtq-youths-use-nonbinary-pronouns-n1235204 (20 November, 2023.)

Wikipedia. 2023. Gender Neutrality in Languages with Gendered Third Person pronouns.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gender_neutrality_in_languages_with_gendered_third-person_pronouns#Historical,_regional,_and_proposed_gender-neutral_singular_pronouns (20 November, 2023.)

Zappavigna, Michelle. 2012. Discourse of Twitter and Social Media: How We Use Language to Create Affiliation on the Web. London: Bloomsbury.

Zimman, Lal. 2017. Transgender language reform: Some challenges and strategies for promoting trans-affirming, gender-inclusive language. Journal of Language and Discrimination 1/1: 84–105.

Zimman, Lal. 2019. Trans self-identification and the language of neoliberal selfhood: Agency, power, and the limits of monologic discourse. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 256: 147–175.

Notes

1 For financial support Lucía Loureiro-Porto is grateful to the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities, grant PID2020-117030GB-I00 funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033. Thanks are also due to two anonymous reviewers and the editors of this special issue, whose comments have improved the original version of this manuscript to a large extent. Needless to say, errors or omissions that remain are our responsibility. [Back]

2 Whilst we are writing this paper, the Spanish Real Academia de la Lengua Española (RAE 2023) announces that one of the new entries added to its electronic version 23.7 is precisely no binario ‘nonbinary’, which constitutes just another piece of evidence that standardizing institutions acknowledge the need to find specific vocabulary to refer to nonbinary individuals. [Back]

3 Referring to those individuals by the pronouns they go by would then constitute an example of good manners, although the social network X has lately witnessed a sort of heated debate regarding this issue (Ingram 2023). [Back]

4 In fact, Wikipedia lists some sources for each of the pronouns, but many of them are debatable and, with the aim of keeping the explanation simple, we have decided just to include the first attestation date as currently found in the entry. The Wikipedia list of neopronouns is considerably shorter than that proposed by Baron (2020), which contains over 200 possibilities (Stormbom 2024: 416), as well as other compilations available on online platforms such as Pronouns.page (featuring 19 neopronouns) and Pronouny (which documents over one thousand neopronouns). Consequently, the 16 neopronouns outlined in Table 1 can be confidently regarded as the most commonly utilized sets of NB pronouns. [Back]

5 The term ‘Spivak pronouns’ is attributed to the mathematician Michael Spivak, who first used e/em/eir/eirs/emself in his book The Joy of TEX: A Gourmet Guide to Typesetting with the AMS-TEX Macro Package (see Pronouns.page 2024). [Back]

6 This term originates from Christine M. Elverson, who won a contest in 1975 with the intention of offering an alternative to singular they (see Pronouns.page 2024). [Back]

7 In 2023, after Elon Musk’s acquisition of Twitter (and the change of its name to X), there have been significant changes in the landscape of X analytical platforms, including Followerwonk. The platform no longer remains operational with all the functionalities used for this study, as has been acquired by Fedica (i.e., https://fedica.com/). [Back]

8 The test applied to these data is the Z score test, which calculates the value of z (and associated p value) for two population proportions. This test compares the observed frequency with the expected frequency; the z score is the number of standard deviations from the mean frequency, in such a way that the higher the z score, the lower the likelihood that only chance is affecting the distribution (McEnery et al. 2006: 57). In this case, the value of z is 19.2599. The value of p is < .00001. The result is significant at p < .05 (https://www.socscistatistics.com/tests/ztest/default.aspx) [Back]

9 On most cases, the non-nominative form is in the accusative, because the genitive form has shown to be anecdotal with only 39 cases from almost 2,000 tokens from the dataset. [Back]

10 The value of z is 35.029. The value of p is < .00001. The result is significant at p < .05. [Back]

11 Out of these 1,254 accounts that list gendered pronouns alongside NB ones, 28 also list neopronouns, while 1,226 only list they and she, he or he and she. [Back]

12 The pronoun elle is often listed as a NB in Spanish (e.g. López 2019), which has led us to consider this a NB in this context (instead of the homograph French feminine pronoun). [Back]

Corresponding author

Lucía Loureiro-Porto

Universitat de les Illes Balears

Departament de Filologia Espanyola, Moderna i Clàssica

Facultat de Filosofia i Lletres

Edifici Ramon Llull

Cra. de Valldemossa Km. 7,5

Palma 07122

Spain

E-mail: lucia.loureiro@uib.es

received: November 2023

accepted: July 2024