The creation of the Indonesian TreeTagger for use in LancsBox and CQPweb

The creation of the Indonesian TreeTagger for use in LancsBox and CQPweb

Prihantoro

Universitas Diponegoro / Indonesia

Abstract – TreeTagger is a multilingual tagger capable of performing headword and POS tagging. However, before the completion of this project, Indonesian had not been supported. Thus, corpus query systems employing TreeTagger as a subsystem, such as CQPweb v.3.3.10 and LancsBox v.5, were incapable of annotating Indonesian texts. This context leads to the following research: 1) develop Indonesian language support for TreeTagger, 2) evaluate its performance, and 3) integrate the support into two popular corpus query systems, namely CQPweb and LancsBox, and demonstrate its functionalities. The research procedure can be concisely summarised as follows: training, annotation and evaluation, and incorporation. A pre-annotated corpus and lexicon were used in the training process. Headwords for the lexicon and corpus were semi-automatically added using MorphInd, augmented with expert revisions. The training produced an Indonesian TreeTagger parameter file, whose accuracy for POS and headword annotation was 96 per cent and 91 percent respectively. The parameter file has been incorporated into LancsBox v.6 and CQPweb 3.3.11, enabling support for the Indonesian language.

Keywords – TreeTagger; CQPweb; LancsBox; Indonesian; annotation

1. Introduction

Indonesian is the national and official language of Indonesia (Cohn and Ravindranath 2014: 134). It is a standardised Malay variety, spoken in Indonesia by more than 250 million speakers, as either a first or second language (Eberhard et al. 2022). This makes Indonesian the largest standardised Malay variety compared to other Southeast Asian Malay varieties. In light of this, the availability of corpus tools that support Indonesian is critical for the advancement of Indonesian corpus linguistics research. These tools should ideally be capable of performing at least three corpus-related tasks: 1) corpus data tokenisation, 2) annotation, and 3) analysis (Prihantoro 2022a), all of which are typically performed prior to interpreting corpus data findings.

Currently, a variety of computer programs are available to assist linguists with the three tasks mentioned above. For instance, a raw Indonesian corpus may be firstly tokenised using Sastrawi (Librian 2016) and annotated using IPOSTagger (Wicaksono and Purwarianti 2010) or MorphInd (Larasati et al. 2011). The annotated corpus can then be imported into corpus query systems such as AntConc (Anthony 2024) or WordSmith (Scott 2024), among others, allowing users to query and implement basic to advanced corpus analysis techniques such as concordance, collocation, and keyword analyses.

Unfortunately, the preceding illustration demonstrates the potential difficulties faced by linguists who lack fundamental technical skills. First, multiple programs must be installed. Second, familiarity with the operation of all those programs and their transitions is required. In particular, Sastrawi, IPOStagger, and MorphInd are only accessible through the command line/terminal, whereas others, such as AntConc and WordSmith, are accessible through the Graphical User Interface (GUI).

CQPweb (Hardie 2012, 2023) and LancsBox (Brezina et al. 2018, 2020) are presented as improvements over the aforementioned programs because they allow all three of the tasks to be completed within a single user-friendly system. This enables linguists with limited technical proficiency to avoid the aforementioned complexity. While advanced corpus query functionalities are inherent to CQPweb and LancsBox, tokenisation and annotation tasks are accomplished by incorporating TreeTagger (henceforth TT; Schmid 1999, 2024), which is a tagger for many languages (English, French, German, and Chinese, among others) as a sub-system (i.e., third party software). Unfortunately, prior to completion of this project, an Indonesian TT had not been created, so neither CQPweb nor LancsBox could support annotation for Indonesian texts. This necessitated constructing a TT parameter file for Indonesian, which is referred to as the Indonesian TT. It can assist linguists who wish to annotate Indonesian texts with POS tags and headwords and implement corpus searches using these annotations in CQPweb and LancsBox.

In light of the previous discussion, the aims of the present study are:

(1) to develop Indonesian language support for TT in the form of a TT parameter file;

(2) to evaluate its performance;

(3) and to integrate the parameter file into CQPweb and LancsBox, as well as demonstrating its functionality.

Once the performance-measured Indonesian TT has been developed and integrated into CQPweb and LancsBox, both systems will support Indonesian and may be used to annotate a large corpus to their full capabilities. The present study therefore constitutes a practical contribution while, theoretically, it will allow researchers to carry out advanced quantitative and qualitative analysis by discovering new patterns, profiling texts, and conducting keyword analyses based on headwords or POS annotations, or a combination thereof.

2. Literature review

2.1. Why TreeTagger?

In what follows, I review relevant literature pertaining to the first and second objectives in the study (see Section1). I argue that TT is a suitable system for the development of Indonesian language support, particularly headword and POS annotations. In the context of the Indonesian language, the term ‘headword’ refers to a monomorphemic word, not a lemma. For details, see Prihantoro (2021a, 2021b).

First, in terms of tokenisers, some tools have been developed: see, among others, Sastrawi (Librian 2016) or built-in tokenisers in NLP toolkits such, as the Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK; Bird et al. 2019) and Spacy (Vasiliev 2020). Nonetheless, some POS tagging systems such as MorphInd (Larasati et al. 2011) and TT (Schmid 1999) already include tokenisers. Here, I argue that the use of these systems is more efficient than the use of tokenisers in isolation.

As regards specific existing Indonesian POS taggers, there are several systems that can perform headword and POS tagging tasks on Indonesian texts, namely, the Two-Level Morphological Analyser for Indonesian (TLMA-Ind; Pisceldo et al. 2008), the IPOSTagger (Wicaksono and Purwarianti 2010), MorphInd (Larasati et al. 2011), and Indonesian POS taggers developed by (Rashel et al. 2014; Fu et al. 2018; and Maulana and Romadhony 2021).

TLMA-Ind is a morphological analyser and synthesiser. However, synthesis functionality is not required for this project. In terms of analysis, the system will output a headword and a POS tag, which may be followed by a morphological tag, when given an Indonesian word as input. Example (1) illustrates the output for the input word memukul ‘hit’ (Pisceldo et al. 2008: 149). The word is analysed by its headword pukul ‘hit’, shallow POS category (+Verb), and its morphological tag (+AV).

(1) pukul + Verb + AV

Nevertheless, the TLMA-Ind annotation scheme is extremely inadequate. It is limited to producing only four POS tags: noun, verb, adjective, and (literally) others. POS such as preposition, conjunction, etc. are included in the tag ‘others’. In addition, TLMA-Ind was evaluated against a list of words rather than a testbed corpus. This means that the words have been taken out of context.

In terms of its annotation scheme, the IPOSTagger is more advanced than TLMA-Ind. Unlike TLMA-Ind, which has only four POS tags, the POSTagger has 35 POS tags, including prepositions, interjections, and numerals, among others. These tags are provided alongside word tokens delimited by forward slashes. In contrast to TLMA-Ind, the output is unambiguous. A word token can only have a single analysis. In terms of performance, the IPOSTagger achieved 99 per cent (the best) accuracy when evaluated against a testbed corpus. However, it only outputs POS annotation, which may be considered a drawback (headword annotation is not included). See, for instance, the sample output in (2), obtained from the following input sentence saya berdiri di jalan ‘I stood on the road’.

(2) saya/PRP berdiri/VBI di/IN jalan/NN

I/PRONOUN stood/INTRANSITIVE_VERB on/PREPOSITION road/NOUN

‘I stood on the road.’

Headword annotation appears to be understudied. The documentation for the IPOS tagger, MorphInd, and several other Indonesian POS taggers mentioned above does not report headword annotation evaluation. I would like to bridge this gap by reporting both headword and POS tagging accuracy.

MorphInd is claimed to be a morphological analyser, but it actually includes headword and POS annotation functions. For instance, it analyses mengirimkan ‘send something’ as a word composed of three morphemes (presented as underlying instead of surface forms), meN+, kirim<v>, and +kan. The headword is indicated by a headword POS (here, <v>). The word POS is presented at the end, here _VSA (serb singular active), whose full word analysis is shown (3) and Table 1, below. Although decomposing words into morphemes is one of MorphInd’s strengths, identifying morphemes other than the headword is not the focus of this project.

(3) meN+kirim<v>+kan_VSA

|

Output |

Description |

|

meN |

Underlying form of the active voice prefix |

|

+kirim |

Headword of mengirimkan |

|

<v> |

Headword POS |

|

+kan |

Underlying form of the suffix* |

|

_VSA |

Word tag |

Table 1: Morphological annotation description for example (3)1

Unlike other aforementioned systems, MorphInd has been widely used by scholars (Chung and Shih 2019; Denistia 2023). In its official report (Larasati et al. 2011: 119), the performance of MorphInd was measured in terms of its overall token coverage of 84 per cent. However, scholars report different evaluative measures. Instead of coverage, Denistia (2023: 15) and Prihantoro (2021a: 175) reported that MorphInd’s accuracy was measured at 84 per cent and 89 per cent, respectively, which appears to be the result of the different testbed corpora employed. While Denistia (2023) reported 84 per cent accuracy, her evaluation metric is not coverage and therefore differs from the evaluation metric used in MorphInd.2 Regardless, the output of MorphInd is quite complex. As Larasati et al. (2011: 122) mention, the MorphInd tagset is influenced by the Penn Treebank tagset. 3Thus, it does not seem to fully reflect Indonesian morphosyntax.4

Unlike the foregoing systems, taggers developed by Fu et al. (2018) and Maulana and Romadhony (2021) are not publicly available. Rashel et al.’s (2014) demo tagger is claimed to be available but is in fact inaccessible. Thus, the present review of literature depends solely on their papers, whose linguistic content is very limited. The accuracy of these three taggers is reported at 96 per cent, 79 per cent, and 92 per cent respectively. As for the tagset, the number of tags in Rashel et al.’s (2014) and Fu et al.’s (2018) tagsets are 23 and 29 tags, respectively, but in Maulana and Romadhony’s (2021) tagger, the number of tags is not mentioned. Before the project was completed, TT did not support Indonesian at all. As the tagset and its performance evaluation were still unknown at the time of review, the status of tagset and evaluation is yest unknown before the conclusion of this project. This is shown in Table 2.

|

Tagger |

Tagset |

Evaluation |

Access |

Operation |

Design |

|

TLMA-Ind |

4 |

Precision (89%) |

Accessible |

Terminal |

RB |

|

IPOSTagger |

25 |

Accuracy (99%) |

Accessible |

Terminal |

DD |

|

MorphInd |

39 |

Coverage (84%) |

Accessible |

Terminal |

RB+DD |

|

Rashel et al. (2014) |

23 |

Accuracy (79%) |

Accessible |

Terminal |

RB |

|

Fu et al. (2018) |

29 |

Accuracy (96%) |

NM |

Terminal |

DD |

|

Maulana and Romadhony (2021) |

NM |

Accuracy (92%) |

NM |

Terminal |

DD |

|

TreeTagger |

UNK |

UNK |

Accessible |

Terminal |

DD |

Table 2. Summary of taggers reviewed in this project (NM=Not mentioned, RB=Rule-Based, DD=Data-Driven, UNK=unknown yet as this project was not concluded)

As for the design of a tagger, Table 2 suggests that there are at least two designs: 1) rule-based (or linguistic) and 2) data-driven (or statistical) approaches (a third design is a combination of the two). The differences between these two approaches are concisely described in (Voutilainen 1999: 9–10). Regardless of the fundamental methodological differences, (Prihantoro 2021a: 300) states that, depending on the quality of the resources, the two methods may generate taggers with relatively similar performance.

In terms of evaluation, Table 2 suggests that there are at least three evaluative measures: coverage, precision, and accuracy. I exclude ‘coverage’ here because it only measures the proportion of tokens a tagger recognises correctly, not tokens corresponding to headword or POS tags. Prihantoro (2021a: 242–243) argues that precision suits taggers whose output may be ambiguous, while accuracy suits taggers whose output is unambiguous. Thus, the preference would depend on the characteristics of the output.

Note that all the aforementioned systems can potentially be challenging when users are not skilled in programming, at least at the basic level, both for program installation as well as their operation. MorphInd, for instance, can only be installed on Mac or Unix-like distributions, such as Ubuntu. The Linux subsystem must be installed if it is to be utilised on a Windows machine. Then, subsequent applications must be pre-installed: SVN, Perl, Foma, and Subversion. Operation is performed through a command line or terminal application. TT is no exception. Example (4) illustrates a TT command line to annotate the source.txt file and place the output in the result.txt file.

(4) tree-tagger.exe english.par source.txt result.txt –token –lemma

Note that source.txt requires a format of one token per line, which can be implemented using an existing Perl tokeniser script in the TT system. This regrettably adds another layer of complexity, as the source file must be tokenised before applying the tagging command line. Table 3 shows the difference between input and output file formats. In the latter, headword and POS annotation are added.

|

source.txt |

|

result.txt |

|

|

|

|

Tagger |

Token |

HW |

Tag |

|

|

|

There |

There |

there |

EX |

|

|

|

are |

are |

be |

VBR |

|

|

|

some |

some |

some |

DD |

|

|

|

apples |

apples |

apple |

NN2 |

|

|

Table 3: Input and output format (CLAWS-7 tagset, HW=headword )

A further complication is that the output file must be reformatted based on the format accepted by the preferred corpus query system. Example (5) shows a format accepted by AntConc, which does not include headword annotation. AntConc mandates that the list of lemmas must be maintained in a separate file. Consequently, tokens and lemmas must be extracted and stored as a lemma list.

(5) there/EX are/VBR some/DD apples/NN2

there/EXISTENTIAL_THERE are/ARE some/DETERMINER

apples/PLURAL COMMON NOUN

To summarise, I argue that it is more effective to develop the Indonesian TT from the ground up, despite the complexities that it presents. This is due to the fact that the TT has been integrated as a subsystem of several corpus query systems, including CQPweb and LancsBox. Once the Indonesian TT is incorporated into LancsBox and CQPweb, end users will be able to bypass all of these complex processes by simply clicking a button to perform POS and headword annotation, as well as Indonesian corpora searches and other advanced functionalities (collocation, keyword, etc.) based on this annotation. While the TT’s accuracy was routinely measured at between 94 per cent and 96 per cent (Schmid 1999), it should be noted that at the time the project was carried out, it was unknown to what extent the accuracy was consistent for Indonesian. Evaluation methods will be explained in more detail in Section 3, and their implementation will be described in Section 4. As with other languages, TT can perform headword as well POS annotation and can be used to analyse more than 20 languages, excluding Indonesian, prior to the completion of this project.

2.1. Why CPQweb and LancsBox?

In relation to the third objective of this project, I argue that CQPweb and LancsBox are two state-of-the-art sophisticated corpus query systems that are suitable for this project. Note that other query systems are also in use, including Sketch Engine (Kilgarriff et al. 2014) and English-Corpora (Davies 2024). Other popular corpus tools are AntConc and WordSmith. These are the main corpus linguistic tools surveyed by Gomide (2020).

These systems can be divided into two major categories: web-based and desktop applications (or third- and fourth-generation corpus linguistic tools as shown in Gomide (2020: 24–26). CQPweb, Sketch Engine, and English-Corpora applications are web-based. Users are not required to install anything on their computers. These applications are accessible via a variety of internet browsers, including Google Chrome, Safari, or Firefox, among others, regardless of the operating system (Windows, Mac, or UNIX distribution). Conversely, LancsBox, WordSmith, and AntConc are computer applications which users must install. Every system has its own specifications. For instance, WordSmith cannot be installed on Mac or UNIX-like operating systems. Users are therefore required to install additional software, such as Wine or Parallel.

All of the aforementioned systems are user-friendly in that they do not require users to be able to code or program using languages such as Bash, Python, PHP, Perl, and the Windows command line, among others. Only three of the aforementioned systems are capable of performing POS and headword annotation: Sketch Engine, CQPweb, and LancsBox. These are the candidates for the incorporation of the Indonesian TT. The three systems have integrated TT into their operations. Sketch Engine, however, is excluded because it requires backend access to incorporate the Indonesian TT, which I do not have access to. Moreover, Sketch Engine is a proprietary system, while CQPweb and LancsBox are open-source systems.

Regarding LancsBox, there are two ways to implement the Indonesian TT. The first is from the server, which I do not have access to, and the second is from the configuration of the resource file, which is freely accessible to users once downloaded to a computer. Therefore, LancsBox is preferred. CQPweb is similar to Sketch Engine in that developer access is required, but the author has access to CQPweb admin control. Thus, the primary reasons for selecting CQPweb and LancsBox are that they are non-commercial and open-access systems. In addition, CQPweb and LancsBox represent two distinct types of advanced corpus query systems: web-based and desktop applications. Note that LancsBox here is different from LancsBox X (Brezina and Platt 2024), another variant of LancsBox which uses Spacy instead of TT for POS tagging purposes.

3. Methodology

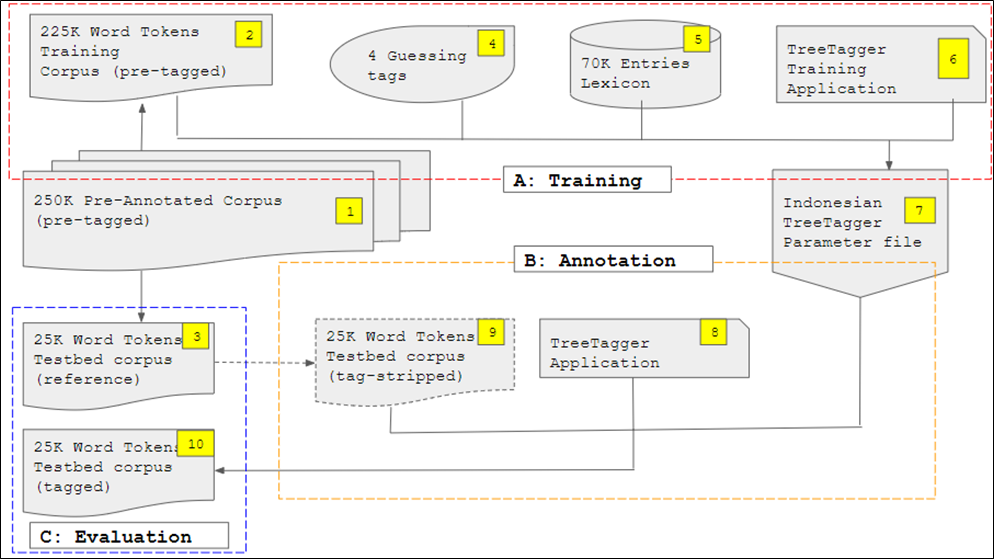

The research procedure in this project is presented in chronological order, with emphasis on sections pertinent to the research objectives. The procedure can be divided into four phases: 1) training, 2) annotation and 3) evaluation (whose process is shown in Figure 1), and, finally, 4) incorporation.

In accordance with the TT framework, I created the Indonesian TT (the TT parameter file used for tagging Indonesian texts) using a data-driven approach (see Section 2.1), which requires a training process. First, I prepared a number of resources to train the TT and output a parameter file (language support for the TT), as prescribed by Schmid (1999, 2024). The resources are a training corpus, a lexicon, a file containing tags for guessing unknown words (referred to as open-class file), and a TT training application.

I chose a 250,000-word pre-annotated Indonesian corpus ([1] in Figure 1) made available by Dinakaramani et al. (2014) to ensure the quality of the training corpus. The corpus was manually annotated and checked using its own tagset (which I will refer to here as the UI tagset), whose creation is discussed in Dinakaramani et al. (2014).

Figure 1: Training, annotation, and evaluation phases

The corpus was then divided in two parts. The first 25,000 words ([3] in Figure 1) were extracted as a reference testbed corpus, which was used in the final stage to evaluate the application’s performance in the evaluation phase.

The remaining words, 225,000k ([2] in Figure 1), served as the training corpus, a resource which was processed by the TT training application ([6] in Figure 1) to create the Indonesian TT ([7] in Figure 1) in the training phase. In addition to the training corpus, another resource required to create the Indonesian TT is the lexicon, a file containing a list of words with the corresponding tags, and if possible, headwords ([5] in Figure 1), and open ([4] in Figure 1) class file. The lexicon was compiled by adapting entries from The Great Indonesian Dictionary (Bahasa 2005), or abbreviated as KBBI III, to TT format. In terms of the number of words, the lexicon (around 70,000 words) is just around 30 per cent of the training corpus. However, it is larger in terms of coverage because all words are unique (different from the training corpus in which the same words may be repeated). The lexicon is expected to improve the coverage of the Indonesian TT.

The open class file consists of possible tags for unknown words to anticipate paucity in the training corpus and lexicon. If a word tag (and headword) is still unknown by the Indonesian TT, even after consulting the corpus and lexicon, the program will use orthographic cues to supply a most likely tag. For instance, when an unknown Indonesian word begins with pe- and ends with -an, the most likely tag is NN because, in the training corpus and lexicon, the majority of words with the same orthographic context are tagged NN. To prevent the program from tagging the unknown word using closed class tags, the list of the content word tags was made explicit in the open class file.

I inspected the words in the testbed corpus against the words in the corpus and lexicon. The output was a list of words in the testbed corpus that were not present in the training and the lexicon. There were no function words (such as prepositions or conjunctions), but all the words were content words (nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs). Therefore, five content word tags were selected for guessing, namely, NN (noun), VB (verb), JJ (adjective), RB (adverb) and NNP (proper noun), ruling out the probability of these unknown words to be categorised into function words.

Once all the components were complete, I began the training phase, which aimed to create the Indonesian TT, the parameter file, and a language model file for tagging Indonesian texts. The training ([A:Training] in Figure 1) was administered within a TT environment using the abovementioned resources (training corpus, lexicon, guessing tags, and the TT training application: an application used to create a parameter file for tagging from the aforementioned resources). The training for the POS tags and headwords is an integrated process, not a separate one. When the TT training application was applied to the training corpus and lexicon, it read all information (token, POS tag, headword) to build a language model. The result was an Indonesian TT parameter file ([7] in Figure 1). This concluded the training phase.

The performance of the Indonesian TT parameter file was then evaluated in the two next phases: annotation and evaluation. In the annotation phase, the parameter file was first applied to the testbed that had its tags and headwords stripped ([9] in Figure 1) using TT application ([8] in Figure 1). This concluded the annotation phase,

In the evaluation phase, the output ([10] in Figure 1) was compared to the headword and POS tags of the reference testbed ([3] in Figure 1). Performance evaluation is expressed in (%) accuracy: the percentage of tags and headwords correctly tagged. This is because, by default, the TT does not produce ambiguous output.

In addition, as demonstrated by the evaluation of taggers in different languages such as Tamil (Thavareesan and Mahesan 2020), Korean (Park and Seo 2015), and Turkish (Can et al. 2017), among many others, accuracy is a common metric for measuring POS tagger performance. Evaluation is relevant to the second objective, which is to assess the performance of Indonesian TT. This concludes the evaluation phase.

The last phase was the incorporation of the Indonesian TT into LancsBox and CQPweb. I will demonstrate how to include the parameter file in the configuration of the LancsBox resource file so that it can be used to tag Indonesian texts. As for CQPweb, I will demonstrate how users can utilise the ‘install your own corpus’ functionality, which allows them to select the Indonesian TT as the language support. This is relevant to the third objective of this project.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. The Indonesian TT

The construction of the Indonesian TT is described in this section. The creation of TT language support requires four resources: 1) a training corpus, 2) a lexicon, 3) a guesser list, and 4) a tree-tagger training application (already provided in the TT environment).

As for the creation of the training corpus, the pre-annotated corpus (Dinakaramani et al. 2014) was downloaded from Fam Rashel’s Github repository (Rashel 2016). The file was saved as training.txt. As mentioned in Section 3, the first 25,000 words were extracted and used to create a testbed corpus. This extraction was extended to line 25020 (see Table 4) to guarantee that the final sentence was completely extracted. The resulting reference testbed was named ‘testbed-reference.txt’.

|

Line number |

Token |

Gloss |

|

25001 |

Pemerintah |

‘Government’ |

|

25002 |

Juga |

‘Also’ |

|

25003 |

Melakukan |

‘Do’ |

|

… |

… |

… |

|

… |

… |

… |

|

25017 |

Untuk |

‘To’ |

|

25018 |

Meningkatan |

‘Improve’ |

|

25019 |

Kesiagaan |

‘Readiness’ |

|

25020 |

. |

. |

Table 4: Extension to 25,020 tokens for the testbed corpus

As for the lexicon, entries were obtained from KBBI III, downloaded from the Kateglo repository (Lanin et al. 2019). These are all full-form entries that are linguistically more comprehensive than root-form lexicons (Prihantoro 2022b) and vocabulary indexes (such as Lun et al. (2023). Several modifications to the lexicon format and content were implemented. First, information other than entries and their respective POS tags was removed. The tagset used in the lexicon had not been adapted to match the tagset used in the training corpus.

I chose to adapt the KBBI tagset (the tagset used in the lexicon) to form the UI tagset (Dinakaramani et al. 2014), because the latter is more fine-grained than the KBBI tagset. The KBBI tagset only consists of noun, verb, adjective, adverb, numeral, and kata tugas’, which is a bin tag for other tags not yet covered (prepositions and conjunctions, among others), thus can simply translate to the tag ‘others’. Ordinal and cardinal numerals, for instance, are subsumed under numerals in KBBI using the tag num. However, if a comparison is made Larasati et al.’s (2011) tagset is mor fine-grained than the UI tagset. Prihantoro (2021b) argues that some of Larasati’s tags are incompatible with Indonesian morphosyntax. For example, VSA stands for verb singular active. The incorporation of ‘singular’ appears to have been influenced by English grammar, in which verbs are marked according to their subject (singular or plural). The tagset developed by Wicaksono and Purwarianti (2010) is slightly more refined than the UI tagset. For instance, it distinguishes between transitive and intransitive verbs. Nonetheless, transitivity must be determined at the level of syntax, which is beyond the scope of this study.

After selecting the tagset, I moved on to tagset adaptation. When UI tags were more specific, I manually revised the POS tags. For instance, the tag num for pertama ‘first’ was converted into OD (OrDinal number), while satu ‘one’ was converted into CD (CarDinal number). In some instances, a simple find-replace operation could be used to effectively adapt the lexicon. For instance, the verb tag v in KBBI could simply be replaced with the VB (VerB) tag.

The absence of headwords in the lexicon was an issue because TT requires the token-tag-headword sequence to be present in each entry line (each one delineated by a tab), as shown in Table 5. Ambiguous entries (e.g., bisa as a modal verb ‘able to’ and also as a noun ‘venom’) must be on the same line. Following the tag-headword pair for the first meaning, another tag-headword pair for the second meaning must be included in the same line. This differs from the SANTI-morf lexicon (Prihantoro 2022b) in which ambiguous entries must be placed on separate lines.

|

Type |

Entry |

Tag1 |

HW1 |

Gloss1 |

Tag2 |

HW2 |

Gloss2 |

|

Unambiguous |

Mengambil |

VB |

Ambil |

|

|

|

|

|

Ambiguous |

Bisa |

MD |

Bisa |

‘Able to’ |

NN |

Bisa |

‘Venom’ |

Table 5: Unambiguous and ambiguous entry format (HW=headword)

To ensure that all lexical items in the lexicon were associated with their corresponding headwords, I applied MorphInd. Note that MorphInd’s output (as shown in Section 2.1) includes affixes, headword POS and full word tags. These elements were omitted to ensure the lexicon was formatted correctly.

To ensure that every lexical item in the training corpus is present in the lexicon, the content of the training corpus training.txt was incorporated into the lexicon. Similar to the initial version of the lexicon discussed earlier, the corpus lacked a headword; only lexical items and their corresponding POS tags were included. I added a headword to each lexical item using MorphInd to make the content compliant with the lexicon format. MorphInd managed to supply 98 per cent of the lexical items’ corresponding headwords. Out of these, 92 per cent of the headwords were supplied correctly. I then manually revised the analyses until they were 100 per cent accurate and added the missing headwords. Table 6 illustrates some of the lexical items whose headwords were incorrectly supplied.

|

Lexical item |

Gloss |

Incorrect HW |

HW Corrected |

|

Menurut |

‘According to’ |

Menurut |

Turut |

|

Menjelang |

‘Near’ |

Menjelang |

Jelang |

|

Menarik |

‘Pull’ |

Menarik |

Tarik |

|

Pesaing |

‘Competitor’ |

Pesaing |

Saing |

|

Mendatang |

‘Next’ |

Mendatang |

Datang |

Table 6. Sample of incorrect headwords (HW=headword)

The next step was to remove duplicates because some of the original lexical items in the lexicon were identical to lexical items obtained from the corpus. The final lexicon output was saved as lexicon.txt.

As for the third element, guessing tags, only four tags were used and all were content word tags, namely, VB, NN, JJ, NNP (verbs, nouns, adjectives, and proper nouns). These tags were stored in guess.txt.

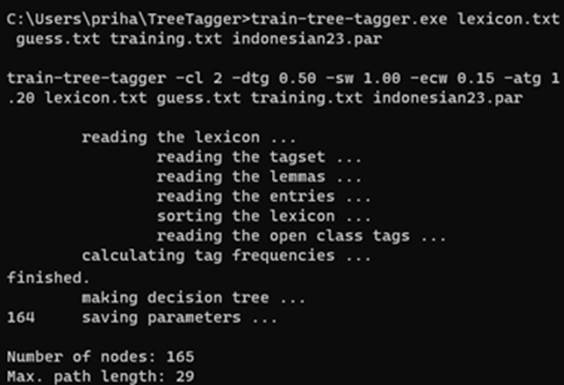

All the resource files (lexicon=lexicon.txt, list of tags for guessing=guess.txt, and training corpus=train.txt) required to build an Indonesian parameter file for TT have been completed. Training was conducted in a TT environment using a training-tree-tagger.exe file. The command line below executed the training process, resulting in a parameter file called ‘indonesian23.par’, as shown in (6).

(6) train-tree-tagger.exe lexicon.txt guess.txt train.txt indonesian23.par

The creation of Indonesian TT (Figure 2) finalised the training process, ensuring that the first objective of this paper was accomplished. The next step will be discussed in what follows and deals with annotation and evaluation.

Figure 2: An Indonesian TT parameter file created

4.2. Annotation and Evaluation

In this section, I will discuss the second objective of this project: namely, evaluating the performance of the Indonesian TT. First, a copy of the testbed-reference.txt was created and renamed as ‘testbed-stripped.txt’. The latter is the actual testbed. Next, all tags in the actual testbed-stripped.txt were removed. Subsequently, both the TT application and the Indonesian parameter file were used to tag the actual testbed. The command line that executed the annotation can be seen in (7).

(7) tree-tagger.exe indonesian23.par testbed-stripped.txt testbed-tagged.txt -token -lemma

The evaluation was conducted by comparing the reference testbed’s annotations, which were regarded as the gold standard, with the annotations obtained from the Indonesian TT (the resulting file was testbed-stripped.txt) whose accuracy measure is defined as follows: (correctly annotated tokens/all tokens) * 100 = accuracy (%). Tokens are considered to be correctly annotated only if they contain matching annotations. Table 7 illustrates 100 per cent accuracy for both POS and headwords for five tokens, because annotations from the actual testbed match all annotations from the reference testbed.

|

Gloss |

Token |

RT |

AT |

TM |

HWM |

||

|

|

|

Token |

Tag |

Token |

Tag |

|

|

|

‘Rise’ |

Naik |

Naik |

VB |

Naik |

VB |

Yes |

Yes |

|

‘From’ |

Dari |

Dari |

IN |

Dari |

IN |

Yes |

Yes |

|

‘IDR’ |

Rp |

Rp |

SYM |

Rp |

SYM |

Yes |

Yes |

|

‘50’ |

50 |

50 |

CD |

50 |

CD |

Yes |

Yes |

|

‘Become’ |

Menjadi |

Jadi |

VB |

Jadi |

VB |

Yes |

Yes |

Table 7: Matching segments (RT=Reference testbed, AT=Actual testbed, TM=Tag match HWM=headword match)

When compared to previous POS tagger studies, this is the first study that measures the performance of headword annotation. In studies on the Indonesian POS tagger reported in Section 2 (Wicaksono and Purwarianti 2010; Larasati et al. 2011; Rashel et al. 2014; Fu et al. 2018; Maulana and Romadhony 2021) headword annotation is not measured. The fact that the accuracy of headword annotation is left unmeasured, however, seems to be a common phenomenon in studies reporting the creation of taggers for other languages such as Tamil (Thavareesan and Mahesan 2020), Korean (Park and Seo 2015), and Turkish (Can et al. 2017). Prihantoro (2021a) evaluated the accuracy of MorphInd’s headword annotation (89%). Nevertheless, that study is about a morphological annotation system, not about a POS tagger.

One of the possibilities why the accuracy of headword annotation does not exceed 94 per cent is because TT does not know how to lemmatise proper nouns that it has not seen in training. Except for proper nouns in the training corpus that have been lemmatised, all proper nouns are marked as ‘unknown’. For instance, there are six Mayapada ‘the name of a private bank’ in the testbed corpus, but none in the training corpus. As a result, all of the headword annotations for each token are ‘unknown’, and thus do not match. Instead of giving ‘unknown’, it might be best to copy the word as a whole into the headword slot. Note that in a corpus query, it is less likely for a user to search for a proper noun by looking at the headword. The rate of incorrect headword-annotated by POS categories can be observed in Table 8.

|

Word class |

Percentage |

Example |

|

Proper noun |

33 |

Mayapada, Adaro, Xenia |

|

Common noun

|

25

|

Perkemahan ‘camping ground’, kekhalifahan ‘caliphate’, peremasan ‘squezzing process’ |

|

Verb

|

27

|

Menjelang ‘slightly before’, menorehkan ‘inscribe’, melempari ‘throw something repeatedly’ |

|

Adverb

|

8

|

Secepatnya ‘as soon as possible’, sejujurnya ‘honestly’, semestinya ‘as it must have’ |

|

Adjective |

7 |

Terendah ‘lowest’, seimbang ‘ugliest’, terjelek ‘worst’ |

Table 8: Rate of incorrect headword annotation by POS categories

Another cause of errors is the paucity in the training corpus or lexicon (or both), whether missing entries or inaccurate lemmatisation. For instance, the headword of berkeliaran ‘wander’ is keliar. However, in the lexicon and the training corpus, the headword of berkeliaran is berkeliaran. This was overlooked during my earlier inspection, and consequently, TT made this error. In the future, a more thorough examination will be conducted.

In terms of POS tagging accuracy, the Indonesian TT was only three per cent less than Wicaksono and Purwarianti’s (2010) tagger, but four per cent better than the most recent Indonesian tagger developed by Maulana and Romadhony (2021). Nonetheless, I argue that a better comparison should be made using Rashel et al.’s (2014) study, as we employ the same tagset and training corpus. Here, the Indonesian TT performed 17 per cent better than Rashel et al.’s (2014) tagging experiment. This is summarised in Table 9. Note that both TT and Rashel et al.’s (2014) taggers differ slightly in terms of tagger design; the former adopts a data-driven approach, while the latter is rule-based. I suspect that the linguistic rules embedded in Rashel et al.’s (2014) resources may not be detailed enough, thus resulting in lower performance.

|

Tagger |

POS Tagging |

Headword |

|

Rashel et al (2014) |

79 |

NA |

|

Wicaksono and Purwarianti (2010) |

99 |

NA |

|

Maulana and Romadhony (2020) |

92 |

NA |

|

MorphInd (2011) |

89 |

89 |

|

Fu et al. (2018) |

95 |

NA |

|

The Indonesian TreeTagger |

96 |

91 |

Table 9: Headword and POS tagging accuracy percentages

I then conducted further tests by compiling data for five alternative testbed corpora from texts not included in the corpus that derives the training corpus. These texts were created by extracting more than 25,000-word token texts from the Indonesian corpus data in the Leipzig Corpora Collection (Quasthoff et al. 2014) from 2016 to 2020.

As shown in Table 10, it turns out that POS tagging performance varies between 92 per cent and 96 per cent, whereas headword annotation performance varies between 87 per cent and 94 per cent. The mean values for POS and headword annotation are 94 per cent and 91 per cent respectively. The precision of POS tagging remains above the threshold established by Schmid (1999), whereas the precision of headword annotation is below it. That the accuracy of headword annotation is always lower than POS tagging requires further examination. One possibility for this to happen is the nasalisation rule in Indonesian when affixation takes place. The morphophonological alternation invoked by this nasalisation rule translates to orthography (Prihantoro 2021a), causing some forms to be failed to be reduced into the correct headword forms to consonant alternation or deletion (e.g., men ‘ACV’ + tanam ‘plant’ > men +[t]anam = menanam ‘plant’ ). In testbed version 4, their accuracy is identical. This is an outlier as compared to other versions, but similar to the findings in Prihantoro’s (2021a). Nonetheless, the performance evaluation of the Indonesian TT has been completed.

|

Alternative Testbed |

Pos Tagging Accuracy |

Headword Tagging Accuracy |

|

Version 1 |

96 |

94 |

|

Version 2 |

92 |

87 |

|

Version 3 |

92 |

92 |

|

Version 4 |

95 |

91 |

|

Version 5 |

94 |

91 |

|

Mean |

94 |

91 |

Table 10: Headword and POS tagging accuracy percentages

4.3. LancsBox v.6.0 and CQPweb v.3.3.11

LancsBox v.4 (Brezina and Platt 2024) and v.5 (Brezina et al. 2020) lacked Indonesian language support, as did CQPweb 3.3.10 and earlier versions. Regarding the third aim in the study, in what follows, I demonstrate that support for the Indonesian language has been added to LancsBox version 3.6 and CQPweb version 3.3.11.

4.3.1. LancsBox v.6.0

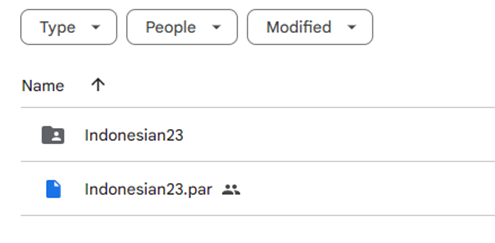

First and foremost, ensure that all required resource files have been downloaded. As pointed out in Section 4.1, the first file required is the Indonesian TT parameter file (indonesian23.par). Other LancsBox specific resource files, such as a list of acronyms, are stored in a folder named ‘Indonesian23’. These files are accessible from this repository (https://tinyurl.com/indonesian23), as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: The Indonesian language support resource files for LancsBox

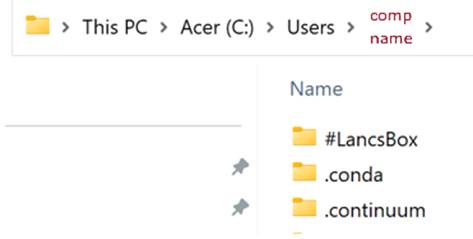

Second, ensure that LancsBox v.6 is the version of LancsBox installed on the computer. Next, locate the #LancsBox folder. In Windows, it is accessible via the private user folder on the C disc (C: Users). If LancsBox is properly installed, the #LancsBox folder should be at the top (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Location of LancsBox folder in Windows

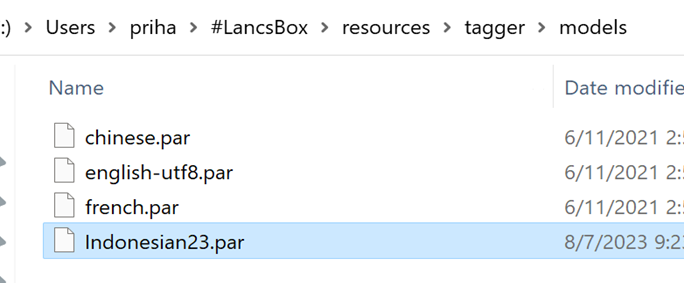

From the #LancsBox folder, go to Resources > tagger > models (C:\Users\comp_name\#LancsBox\resources\tagger\models). The models folder contains the language parameter files supported by LancsBox. By default, the English TT parameter file (english-utf8.par) will be displayed. If LancsBox has been used to analyse other languages, such as Chinese and French, the parameter files for those languages will also be visible (chinese.par and french.par). Then, place the Indonesian parameter (indonesian23.par) file alongside other parameter files (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Parameter files folder in LancsBox

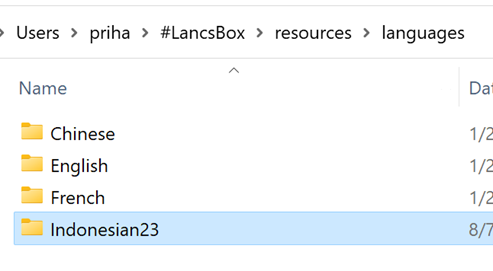

Returning to the Resources folder, navigate to the Languages folder (Resources > Languages). Folders containing languages for which support has been enabled will be visible. For example, the default language will be English. However, if you have activated support for additional languages, the folders for those languages will also be displayed. Insert the Indonesian23 folder here (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Language resource folder in LancsBox

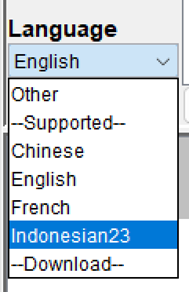

Finally, start LancsBox. If you have started already, close LancsBox and start again. Once you have restarted, go to Language. Click on the triangle button next to English and select Indonesian23 to enable support for the Indonesian language (Figure 7). From this point onwards, use LancsBox normally.

Figure 7: Selecting the Indonesian language support

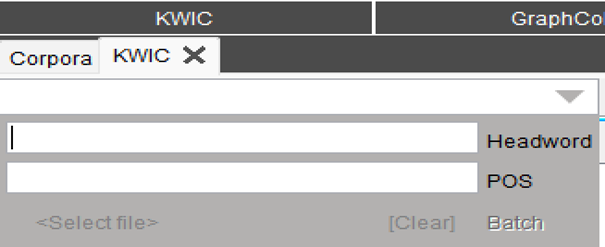

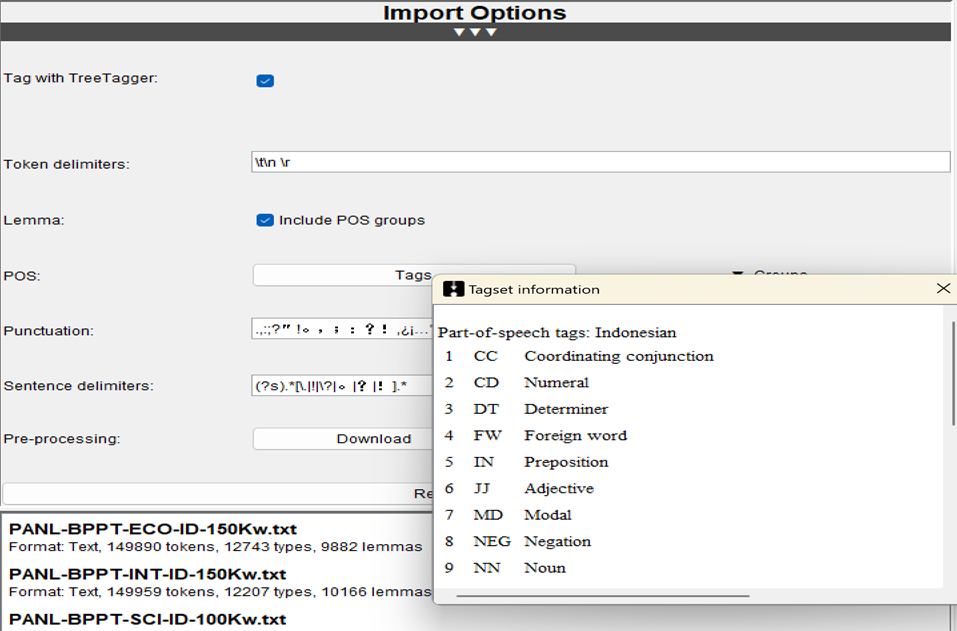

As headword and POS tags have been incorporated, it is now possible to search the annotated Indonesian corpora using lemma and POS tags. In KWIC (Figure 8), for instance, users may enter POS tags or keywords in the query box. The list of tags is accessible via the Tags button within Import Options (Figure 9).

Figure 8: KWIC query box in LancsBox

Figure 9: Indonesian tagset information in LancsBox

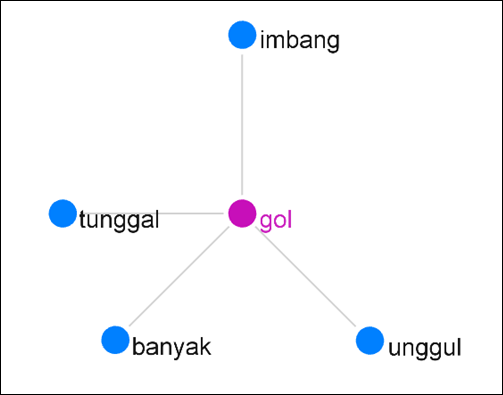

In addition to KWIC, POS and headword filters can also be used in other LancsBox tools. For example, in GraphColl, we can filter a collocation analysis result by POS and/or lemma. Figure 10 shows adjective collocates of gol ‘goal’ in the BPPT-PAN corpus indexed in LancsBox, namely, imbang ‘draw’, tunggal ‘sole’, banyak ‘many’, and unggul ‘excellent’.

Figure 10: Sample of adjective collocates of gol in the BPPT-PAN corpus in LancsBox (LR=5, Stat=Dice, Threshold=Default, View=Lemma, Filter=adjective)

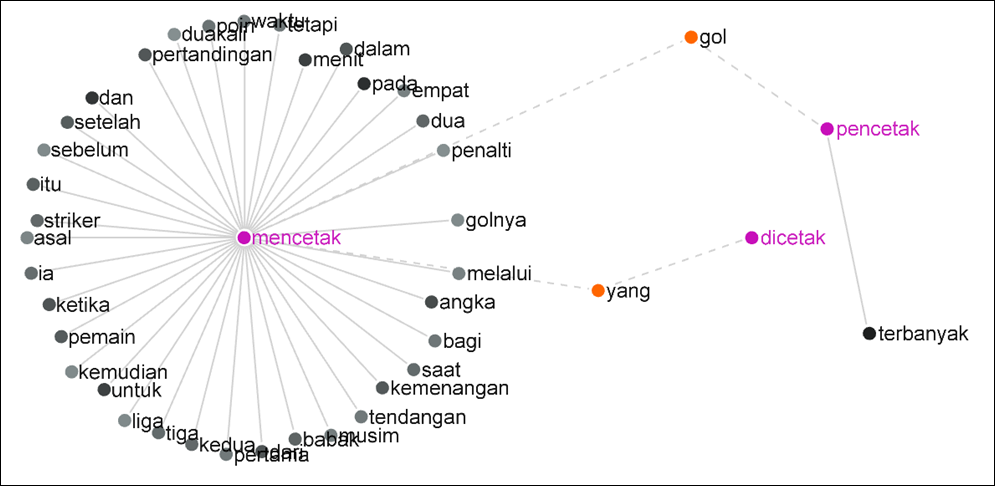

Figure 11 is a GraphColl showing collocates from three words of the same headwords: mencetak ‘print/to score’, pencetak ‘printer/scorer’, and dicetak ‘be scored/printed’. We can observe that gol ‘goal’ is a shared collocate of pencetak ‘scorer/printer’ and mencetak ‘score/print’, but not of dicetak ‘be printed/scored’. The relativiser yang ‘who/that’ is a shared collocate of mencetak ‘score/print’ and dicetak ‘be scored/printed’ (active and passive forms). The remaining collocates are exclusive (not shared). For instance, terbanyak ‘highest quantity’ is an exclusive collocate for pencetak ‘scorer/printer. Likewise, penalti ‘penalty’, and other 43 types (densely populated) are collocates for mencetak ‘score/print’. The overpopulated collocates from menceteak ‘print/score’ were preserved, because if the collocation parameters are changed, collocates from other nodes might be hidden.

Figure 11: Collocation network of three words from the same headword in the BPPT-PAN corpus in LancsBox (LR=5, Stat=LL, Threshold=50.0, View=Type, Filter=None)

Smart search is a LancsBox feature, but for Indonesian it is still under development. I am developing intelligent search grammars to facilitate rapid pattern retrieval. By entering PASSIVE, for instance, all verbs with passive voice prefixes such as di- and ter- will be included in the search results, as indicated by the KWIC lines below (Figure 12). Unlike POS and lemma annotation, however, this feature is not yet fully developed.

Figure 12: Smart search KWIC outcome for PASSIVE in Indonesian

4.3.2. CQPweb v.3.3.11

As CQPweb is an online corpus query system, users do not need to insert all the required language resource files. In the CQPweb server version 3.3.11, the Indonesian TT parameter file and other required resources have been incorporated. Numerous large Indonesian corpora on CQPweb have been annotated with POS and headwords (such as LCC Indonesian 2023), so users can immediately begin searching without having to perform any additional steps.

Note that users can also install their own corpus in CQPweb. First, navigate to Manage your files under Your Files and Corpora. Then upload your files to the CQPweb server from your desktop computer. Next, select Install corpus with TT (Indonesian) under Install your own corpus (Figure 13). There is a one-million token limit for those who wish to utilise language support. If your corpus exceeds one million tokens, CQPweb will automatically remove any excess tokens.

Figure 13: The Indonesian TT

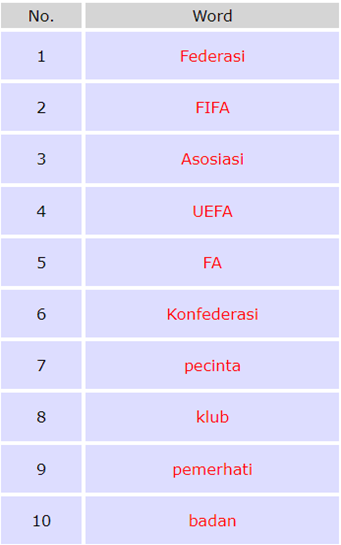

Once your corpus is uploaded, you can search it using POS tags and headwords. The list of POS tags can be viewed under the Corpus Info section of the CS UI POS tagset. With the annotated corpus, all CQPweb functionalities are now active. For example, tags can be used to filter collocates. Figure 14 shows noun collocates of the node sepakbola ‘football’. We can see that some collocates are institutional, such as federasi ‘federation’ and konfederasi ‘confederation’, and some are proper names, namely, FIFA, UEFA, and FA.

Figure 14: Top-10 collocates of sepakbola in LCC Indonesian 2023 CQPweb

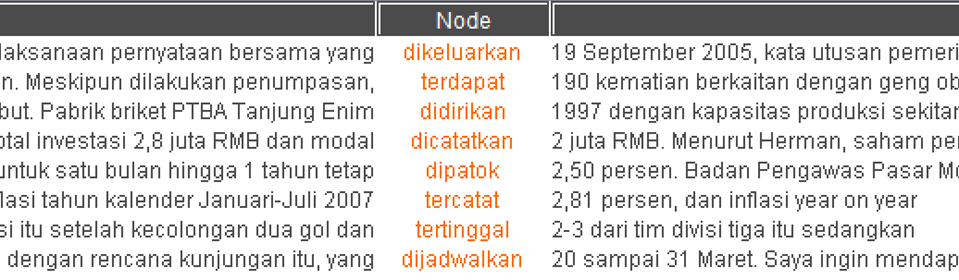

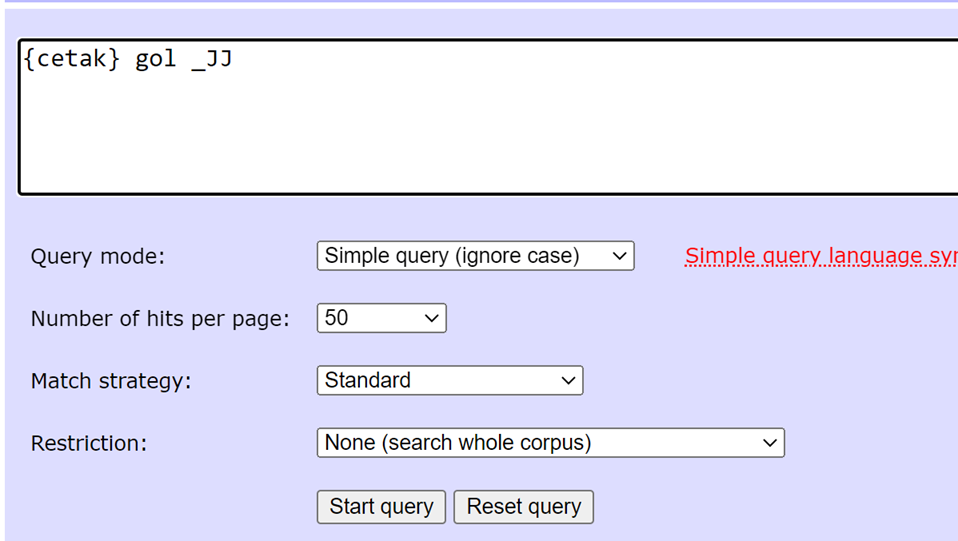

We can also retrieve complex patterns by combining headword and POS tags in a query. For instance, the query {cetak} gol _JJ retrieves the following word combinations: all words whose headword is {cetak} followed by gol ‘goal’ and ending with any adjective (Figure 15).

Figure 15: Sample of a query that includes headword and POS based annotation (LR=3, Stat=Dice Coefficient, Threshold=Default, View=Word, Filter=noun)

This query combines orthographic, headword, and POS tags searches. Table 11 provides the user with a number of instances in the concordance lines, such as pencetak gol terbanyak ‘top goal scorers’, mencetak gol cepat ‘scored a quick goal’, and mencetak gol penting ‘scored an important goal’, among others.

|

|

Left Context |

Node |

Right Context |

|

1 |

jajaran_NN |

pencetak_NN gol_NN terbanyak_JJ |

Barcelona_NN |

|

|

line-up_SC |

scorer_NN goal_NN most_JJ |

Barcelona_NN |

|

|

‘groups |

of top goal-scorers |

in Barcelona’ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

berhasil_VB |

mencetak_VB gol_NN cepat_JJ |

pada_IN |

|

|

succeed_VB |

score_VB goal_NN quick_JJ |

at_IN |

|

|

‘managed to |

score a quick goal |

at the’ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

juga_RB |

mencetak_NN gol_NN penting_JJ |

untuk_SC |

|

|

also_RB |

score_VB goal_NN beautiful_JJ |

for_SC |

|

|

‘also |

scored a beautiful goal |

for’ |

Table 11: Sample of concordance lines from a complex query (three randomly picked lines)

5. Summary and conclusions

All the objectives of the present research have been achieved. The first objective was the creation of the Indonesian TT. The creation of an Indonesian TT parameter file was shown in Section 4.1. This file can be used to perform headword and POS annotation on Indonesian corpora using TT. The second objective, the performance of the Indonesian TT, was evaluated in Section 4.2. The Indonesian TT achieves a POS tagging accuracy of 96 per cent on the testbed corpus and between 92 per cent and 96 per cent on alternate testbed corpora. In terms of headword annotation, the Indonesian TT achieves 81 per cent precision on the testbed corpus and between 75 and 81 per cent precision on the alternative testbed corpora. As for the third objective, Section 4.3 showed that support for the Indonesian language was added to both LancsBox version 6.0 and CQPweb, as of version 3.3.11 onwards.

The fact that the POS tagging accuracy of the Indonesian TT is between 92–96 per cent is the major limitation of the study, since the percentage is slightly lower than other finer-grained tagset, such as the IPOSTagger. Despite being 2–4 per cent lower, the current 90+ per cent accuracy standard is widely accepted best practice for POS taggers. Also, the IPOStagger does not output headwords, while the Indonesian TT does. In the future, I hope to address existing issues by revising the resources (expanding the training data and enhancing the quality and quantity of the lexicon), by making the tagset more granular, revising incorrect headwords and incorrectly labelled entries, and adding multi-word unit entries. Thorough inspections and revision to POS tags and headwords in the resources will be conducted by inter-rater agreement to improve reliability. This is expected to improve also the headword and POS tagging accuracy of the revised Indonesian TT in the future study.

Regardless of the limitations, the availability of Indonesian language support for LancsBox and CQPweb provides users with more search power. This opens up opportunities to qualitatively or quantitatively amplify data interpretation. Although the project focuses on POS and headword annotation, the findings may also have a bearing on syntactic annotation, as phrase structure can be identified using a combination of POS tags. While the Indonesian TT in this project has been integrated into LancsBox and CQPweb, nothing prevents users with greater technical expertise from integrating the resources into other systems.

References

Anthony, Lawrence. 2024. AntConc v.4.2.4 [Software]. Tokyo, Japan. https://www.laurenceanthony.net/software/antconc/

Bahasa, Pusat. 2005. Kamus Besar Bahasa Indonesia. Jakarta: Badan Pengembangan dan Pembinaan Bahasa.

Bird, Steven, Edward Loper and Ewan Klein. 2019. Natural Language Processing with Python: Analyzing Text with the Natural Language Toolkit. O’Reilly. https://www.nltk.org/book/

Brezina, Vaclav and William Platt. 2024. #LancsBox X. https://lancsbox.lancs.ac.uk/

Brezina, Vaclav, Pierre Weill-Tessier and Tony McEnery. 2018. #LancsBox v.4.x [Software]. Lancaster. http://corpora.lancs.ac.uk/lancsbox

Brezina, Vaclav, Pierre Weill-Tessier and Tony McEnery. 2020. #LancsBox v.5.x [Software]. Lancaster. http://corpora.lancs.ac.uk/lancsbox

Can, Burcu, Ahmet Üstün and Murathan Kurfalı. 2017. Turkish PoS tagging by reducing sparsity with morpheme tags in small datasets. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1703.03200

Chung, Siaw-Fong and Meng-Hsien Shih. 2019. An Annotated News Corpus of Malaysian Malay. https://doi.org/10.15026/94451

Cohn, Abigail C. and Maya Ravindranath. 2014. Local languages in Indonesia: Language maintenance or language shift? Linguistik Indonesia 32/2: 131–148.

Davies, Mark. 2024. English Corpora. [Corpora]. https://www.english-corpora.org

Denistia, Karlina. 2023. Databases on the Indonesian prefixes PE- and PEN. Journal of Language and Literature 23/1: 13–24.

Dinakaramani, Arawinda, Fam Rashel, Andry Luthfi and Ruli Manurung. 2014. Designing an Indonesian part of speech tagset and a manually tagged Indonesian corpus. Proceedings of the International Conference on Asian Language Processing. Kuching: Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers, 66–69. https://doi.org/10.1109/IALP.2014.6973519.

Eberhard, David M., Gary Francis Simons and Charles D. Fennig eds. 2022. Ethnologue: Languages of Asia. Dallas: SIL International.

Fu, Sihui, Nankai Lin, Gangqin Zhu and Shengyi Jiang. 2018. Towards Indonesian part-of-speech tagging: Corpus and models. http://lrec-conf.org/workshops/lrec2018/W34/pdf/3_W34.pdf

Gomide, Andressa. 2020. Corpus Linguistics Software: Understanding Their Usages and Delivering Two New Tools. Lancaster: Lancaster University dissertation.

Hardie, Andrew. 2012. CQPweb — Combining power, flexibility and usability in a corpus analysis tool. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 17/3: 380–409.

Hardie, Andrew. 2023. CQPWeb Lancaster. Lancaster. https://cqpweb.lancs.ac.uk/

Kilgarriff, Adam, Vít Baisa, Jan Bušta, Miloš Jakubíček, Vojtěch Kovář, Jan Michelfeit, Pavel Rychlý and Vít Suchomel. 2014. The Sketch Engine: Ten years on. Lexicography 1/1: 7–36.

Lanin, Ivan, Romi Hardiyanto and Arthur Purnama. 2019. Kateglo Dataset v1.00.20131128. https://datahub.io/aps2201/kateglo_scrape#resource- kateglo_scrape_zip

Larasati, Septina Dian, Vladislav Kuboň and Daniel Zeman. 2011. Indonesian morphology tool (MorphInd): Towards an Indonesian corpus. In Cerstin Mahlow and Michael Piotrowski eds. Systems and Frameworks for Computational Morphology. Berlin: Springer, 119–129.

Librian, Andi. 2016. Sastrawi [Software]. https://github.com/sastrawi/sastrawi.

Lun, Wong Wei, Mazura Mastura Muhammad, Warid Mihat, Muhammad Syafiq Ya Shak, Mairas Abdul Rahman and Prihantoro Prihantoro. 2023. Vocabulary index as a sustainable resource for teaching extended writing in the post-pandemic era. World Journal of English Language 13/3: 181. https://doi.org/10.5430/wjel.v13n3p181.

Maulana, Aditya and Ade Romadhony. 2021. Domain adaptation for part-of-speech tagging of indonesian text using affix information. Procedia Computer Science 179: 640–647.

Park, Youngmin and Jungyun Seo. 2015. Joint model of Korean part-of- speech tagging and dependency parsing with partial tagged corpus. International Journal of Knowledge Engineering-IACSIT 1/1: 49–53.

Pisceldo, Femphy, Rahmad Mahendra, Ruli Manurung and I Wayan Arka. 2008. A two-level morphological analyser for the Indonesian language. In Nicola Stokes and David Powers eds. Proceedings of the Australasian Language Technology Association Workshop2008. 142–50. Hobart: Australian Language Technology Association, 142–150

Prihantoro, Prihantoro. 2021a. An Automatic Morphological Analysis System for Indonesian. Lancaster: Lancaster University dissertation.

Prihantoro, Prihantoro. 2021b. An evaluation of MorphInd’s morphological annotation scheme for Indonesian. Corpora 16/2: 287–299.

Prihantoro, Prihantoro 2022a. Buku Referensi Pengantar Linguistik Korpus: Lensa Digital Data Bahasa. Semarang: Undip Press.

Prihantoro, Prihantoro. 2022b. SANTI-Morf dictionaries. Lexicography 9/2: 175–193.

Quasthoff, Uwe, Dirk Goldhahn and Thomas Eckart. 2014. Building large resources for text mining: The Leipzig corpora collection. In Chris Biemann and Alexander Mehler eds. Theory and Applications of Natural Language Processing. Cham: Springer, 3–24.

Rashel, Fam. 2016. Manually Tagged Indonesian Corpus Data. GitHub. https://github.com/famrashel/idn-tagged- corpus/tree/a0c7a7409a31f2e6a3103778f2621d222525c450

Rashel, Fam, Andry Luthfi, Arawindaamani and Ruli Manurung. 2014. Building an Indonesian rule-based part-of-speech tagger. Proceedings of the International Conference on Asian Language Processing. Kuching: Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers, 70–73.

Schmid, Helmut. 1999. Improvements in part-of-speech tagging with an application to German. In Susan Armstrong, Kenneth Church, Pierre Isabelle, Sandra Manzi, Evelyne Tzoukermann and David Yarowsky eds. Natural Language Processing Using Very Large Corpora. Text, Speech and Language Technology. Dordrecht: Springer, 13–25.

Schmid, Helmut. 2024. TreeTagger: A POS Tagger for Many Languages [Software]. https://www.cis.uni-muenchen.de/~schmid/tools/TreeTagger/

Scott, Mike. 2024. WordSmith v.9.0. Stroud: Lexical Software Analysis. https://ww.lexically.net/wordsmith/

Thavareesan, Sajeetha and Sinnathamby Mahesan. 2020. Word embedding-based part of speech tagging in Tamil texts. Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial and Information Systems. Rupnagar: Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers, 478–482

Vasiliev, Yuli. 2020. Natural Language Processing with Python and spaCy: A Practical Introduction. San Francisco: No Starch Press.

Voutilainen, Atro. 1999. A short history of tagging. Hans Van Halteren ed. Syntactic Wordclass Tagging. Dordrecht: Springer, 9–21.

Wicaksono, Alfan Farizki and Ayu Purwarianti. 2010. HMM based part-of-speech tagger for Bahasa Indonesia. Proceedings of 4th International Malay and Indonesian Language Workshop Jakarta: Computer Science.

Notes

1 Note both surface and underlying forms are identical for -kan. [Back]

2 For a qualitative evaluation of MorphInd, see Chung and Shih (2019) and Prihantoro (2021b). [Back]

3 https://www.sketchengine.eu/penn-treebank-tagset/ [Back]

4 For additional criticism of the MorphInd tagset, see Prihantoro (2021a). [Back]

Corresponding author

Prihantoro

Universitas Diponegoro

Faculty of Humanities

Tembalang Campus, Kota Semarang

Jawa Tengah 50275

Indonesia

E-mail: prihantoro@live.undip.ac.id

received: June 2024

accepted: September 2024