Spanish EFL learners’ use of contrastive linking adverbials across three CEFR levels and gender

Spanish EFL learners’ use of contrastive linking adverbials across three CEFR levels and gender

Carmen Maíz-Arévalo

Complutense University of Madrid / Spain

Abstract – The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (2001) and its Companion Volume (2020) emphasise the importance of linking expressions for pragmatic competence. Research on contrastive linking has long attracted scholarly interest; however (pseudo)longitudinal studies across different levels or whether gender may affect learners’ written production in this respect have been neglected. This study aims to address this gap by analyzing how Spanish English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners at different levels express contrast and whether gender impacts their use of concessive expressions. Surprisingly, lower-level (B1) users show a wide range of expressions similar to higher-level users, while those at B2 levels tend to avoid ‘risky’ options. Interestingly, gender does not significantly influence learners’ use of connectors in this corpus, contradicting earlier findings that suggested female learners use more connectors than males.

Keywords – Spanish EFL learners; CEFR/CV descriptors; contrastive connectors; gender.

1. Introduction

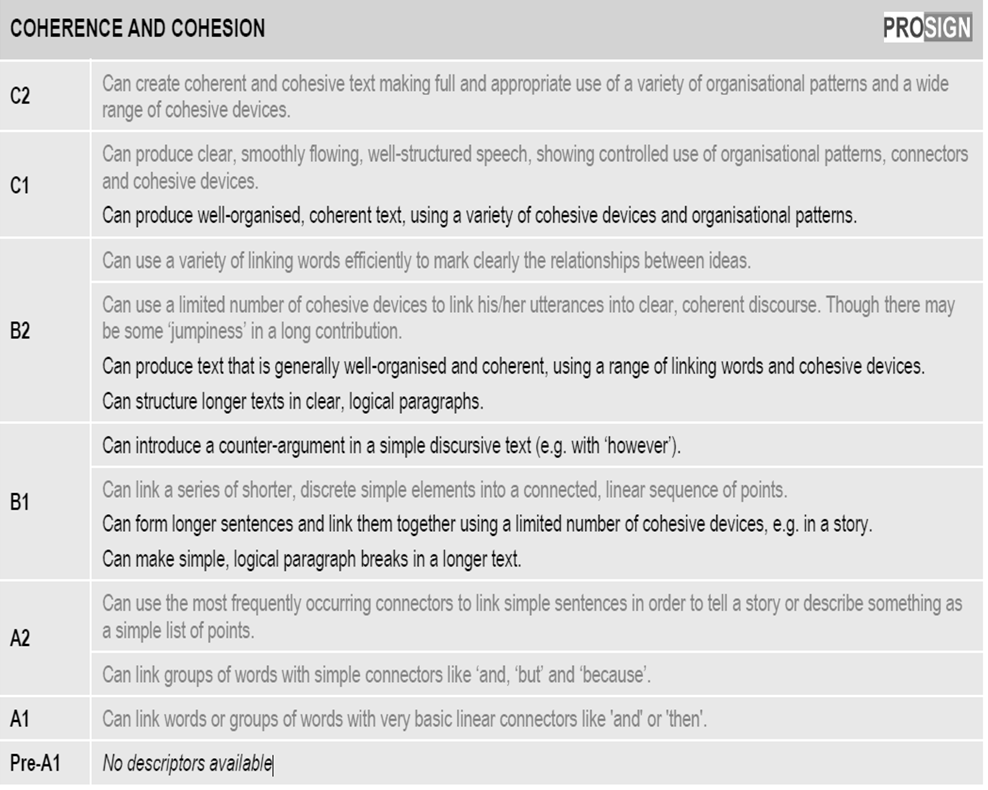

According to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) (Council of Europe 2001) and its Companion Volume (CV) (Council of Europe 2020), learners of a foreign language should acquire three communicative language competences: linguistic competence, sociolinguistic competence, and pragmatic competence. Pragmatic competence encompasses thematic development, which is concerned with “the ability to design texts, including generic aspects like Thematic development and Coherence and cohesion” (CV 2020: 139). Coherence and cohesion refer to the way “in which the separate elements of a text are interwoven into a coherent whole by exploiting linguistic devices such as referencing, substitution, ellipsis and other forms of textual cohesion, plus logical and temporal connectors and other forms of discourse markers” (ibid., 142).

The study of linking adverbials cohesive devices by EFL learners has attracted much scholarly attention for decades, with a special focus on the use of adverbs (e.g. Gilquin and Paquot 2008; Yilmaz and Dikilitas 2017, among many others), often in contrast with native speakers/writers’ use, a common methodological approach being that of contrastive interlanguage analysis (Granger 2015). Research has shown that learners do not appear to find it too problematic to employ time and place as logical connectors. However, this does not seem to be the case with concessive connectors such as however or yet, which has been shown to be harder to master for EFL learners (Celce-Murcia and Larsen-Freeman 1999).

In the case of L1 Spanish EFL learners, the adverbial expression of contrast has proven to be particularly difficult, with learners both transferring from their L1 and overusing the same devices (Pérez-Paredes et al. 2012; Carrió-Pastor 2013; Jiménez Catalán and Ojeda Alba 2014; Mora Díaz and Gómez Orjuela 2021; Faya-Cerqueiro and Martín Macho-Harrison 2022, among others). Nevertheless, these studies have focused on the analysis of different cohesive devices at specific levels rather than contrasting the use of such devices across different levels and in connection with the sociological variable of gender. The aim of this paper is to redress this imbalance by analysing contrastive connectors in a learner corpus across the levels B1, B2, and C1 to find out to what extent (if any) linguistic proficiency and gender influences the way learners employ these connectors in their opinion essay writings.

There are two reasons for choosing these three levels (B1, B2, and C1). On the one hand, according to the CEFR and the CV, learners should be able to use cohesive devices from level B1 onwards, augmenting their range proportionally to their level. The description is rather vague as it is not clear what this ‘range’ actually means. Thus, the B1 descriptor claims that students “can introduce a counter-argument in a simple discursive text (e.g. with however),” while the B2 descriptor states that students “can produce text that is generally well-organised and coherent, using a range of linking words and cohesive devices” (my emphasis). Moving up, at the C1 levels learners are expected to be able to “produce well-organised, coherent text, using a variety of cohesive devices.” On the other hand, these are the three levels under scrutiny in the FineDesc Project,1 within which the present research is encompassed.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 has been divided into two subsections. Section 2.1 describes the theoretical background, with special attention to previous taxonomies of contrast devices and the rationale behind the choice of the linking adverbials chosen in the present study. Section 2.2 reviews previous studies on the use of contrast devices by non-native EFL learners, with a special emphasis on Spanish learners. Section 3 describes the methodology, including a detailed explanation of the corpus and the tools employed in the present analysis. Section 4 discusses the findings before presenting the conclusions in Section 5, together with some pointers to future research.

2. Linking adverbials in English Academic Writing

2.1. Linking adverbials as cohesive devices

A review of the theoretical background reveals a lack of consensus regarding nomenclature. Thus, Quirk et al. (1985: 440) term words like however or nevertheless ‘conjuncts’; that is, words that “express the speaker’s assessment of the relation between two linguistic units.” On the other hand, Huddleston and Pullum (2002) prefer the term ‘connective adjuncts’, while Blakemore (2006: 221) uses the term ‘discourse markers’, which is defined as “generally used to refer to a syntactically heterogeneous class of expressions which are distinguished by their function in discourse and the kind of meaning they encode.” Cowan (2008: 615) refers to ‘discourse connectors’ as “words and phrases that, typically, connect information in one sentence to information in previous sentences.” Biber et al. (2021: 137) used the term ‘linking adverbials’, which are said to “express the type of connection between clauses.”

Despite the differences in terminology, all authors establish a clear distinction between linking adverbials and coordinating and subordinating conjunctions. In fact, Biber et al. (2021) specify that coordinators are closely related to linking adverbials, although there are three main syntactic differences:

i) The position of the coordinator is fixed within the clause boundary, while linking adverbials are more flexible. E.g., They nevertheless decided to go camping versus *They but decided to go camping.

ii) Linking adverbials may be preceded by coordinators, while the latter are mutually exclusive. E.g., And nevertheless, they decided to go camping versus *And but they decided to go camping.

iii) Linking adverbials are often marked by commas, while coordinators are not. E.g., Nevertheless, they decided to go camping versus *But, they decided to go camping.

Furthermore, conjunctions are often employed to create shorter and more concise sentences while conjunctive adverbs (or linking adverbials) tend to render more complex sentences. In the present study, and for the sake of space, I will be focusing on linking adverbials of contrast in the written expression of EFL Spanish learners.

Linking adverbials are classified by Quirk et al. (1985: 634) into seven categories, which are further subdivided into ten subcategories. Among these, the contrastive category includes four subtypes: reformulatory (better), replacive (on the other hand), antithetic (conversely), and concessive (however). These four subtypes, however, are not always clear-cut.

More recently, Biber et al. (2021) divide linking adverbials into six categories, one of which is contrast/concession. Regarding their form, they can typically be realised by single adverbs such as nevertheless or still, adverb phrases like even so, and prepositional phrases such as by contrast or on the other hand. For the present study, I will be following this classification given its more comprehensive definition of the contrastive-concessive subcategory and its syntactic characteristics. Thus, I will focus on the analysis of the following two groups of concessive linking adverbials: (i) single adverbs however, nonetheless, nevertheless, yet, and still; and (ii) prepositional phrases on the other hand, by contrast, and in contrast.

2.2. Learners’ use of linking adverbials: Previous research

The analysis of written compositions by learners of English as a foreign or second language (EFL/ESL) has been a subject of scholarly interest for decades, giving rise to a vast amount of research on learners of many different linguacultural backgrounds and L1s such as Arabic (Modhish 2012; Appel 2020; Ahmed et al. 2023), Chinese (Lee 2020; Zhang 2021), French (Granger and Tyson 1996), Hungarian (Tankó 2008), Iranian (Hosseinpur and Pour 2022), Japanese (Narita et al. 2004), Korean (Lee 2013; Ha 2016; Yoon 2019), Norwegian (Hasselgren 1994), or Swedish (Altenberg and Tapper 1998), among many others.

Despite the wide variety of L1s, findings tend to consistently reveal three tendencies (not always mutually exclusive): (i) non-native speakers often exhibit patterns of overuse in contrast to native users (what has been termed the ‘overuse hypothesis’); (ii) EFL learners misuse certain connectors due to transfer from their native language (see Granger and Tyson 1996); and (iii) learners tend to display a limited range of devices in contrast to their native counterparts.

The overuse tendency has, however, been widely reported, often in combination with the lack of variation. For example, in a recent study of over 180 upper-intermediate and advanced Iranian EFL students, Hosseinpur and Pour (2022) showed that the students lacked variation and overused the contrastive markers nevertheless, in contrast, on the other hand, or on the contrary. This tendency has also been reported among Arabic EFL students. Thus, Ahmed et al. (2023) have shown that even high proficiency students rely on but as their preferred adversative connector. These results are in line with previous research on Arabic EFL learners, which additionally proved that users tended to employ both but and however, overusing both connectors and displaying a limited range of devices (Modhish 2012; Appel 2020).

The use of linking adverbials by Chinese learners has also received recent attention. For example, Zhang (2021) provides a comprehensive analysis of adversative and contrastive expressions (both paratactic and hypotactic) by EFL Chinese students, whose usage he contrasts with that of native writers. The author shows that, in contrast to native speakers, Chinese students overuse on the other hand to express contrast but underuse other expressions like however or nevertheless in contrast to native speakers. Other expressions like yet or still with a contrastive meaning are also neglected by his Chinese participants. In conclusion, his study shares with previous studies the fact that non-native learners often overuse a small set of expressions in contrast to the wider range of connectors employed by their native counterparts.

Other Asian speakers have also received scholarly attention. For example, Lee (2013) showed that Korean students significantly overused contrastive markers compared to native writers, who preferred to make implicit statements of contrast. Korean learners lacked variation, with a heavy use of but, and an underuse of other markers like yet and however. These results, interestingly, did not seem to improve when students’ level was higher. Park (2013) also contrasted Korean EFL and native writers, with the former having either a low or an advanced level. She found that both groups showed a preference for but and however, with the non-native writers resorting to more rigid syntactic position than their native counterparts (see also Ha 2016; Yoon 2019).

The use of linking devices by Spanish EFL learners has also been widely studied. For example, Lahuerta Martínez (2002) found that these learners tended to overuse a limited range of three concessive connectors: but, although, and however, although this study is limited since it focuses on the written compositions of only seven participants. Studies based on larger corpora have shown similar results. For example, Rica Peromingo (2012) focused on B1 and B2 Spanish EFL learners, showing that these students used more contrastive connectors than their native peers and that they prefer multi-word units like on the other hand rather than single contrastive adverbs. This overuse hypothesis was also proved by Navarro Gil and Roquet Pugès (2020), who studied a corpus of 50 argumentative essays, written by Spanish EFL learners, among others. These were later contrasted with a native corpus to study the use of adversative linking adverbials, which resulted in non-native speakers using and placing them more often in sentence-initial position. According to the authors, these learners often overuse adversative linking adverbials and tend to employ them in rather fixed positions, often leading to punctuation issues, even if they have an advanced level.

Language transfer has also been reported among Spanish EFL learners, as shown by Neff-van Aertselaer and Dafouz-Milne (2008). After comparing two corpora (one made up of argumentative essays by Spanish EFL university students (with 194,845 tokens), and the other written by British and American students (149,790 tokens)), the authors concluded that:

Regarding textual metadiscourse […] this study shows that both novice groups under-use logical markers (e.g. and, moreover, but, however, nevertheless, yet; etc.) but over-use sequencers (first, second, next, etc.), and the Spanish EFL writers much more so than American university students. This feature may reflect Spanish rhetorical conventions, which favour a progressive argumentation strategy, building up evidence of the same type, clause by clause, while English argumentation strategies prefer setting out the major premise at the beginning and then offering a balanced consideration of the pros and cons. (Neff-van Aertselaer and Dafouz-Milne 2008: 98)

For other authors, however, the fact that non-native writers employ connectors differently from native writers is not so much due to negative language transfer from the formers’ L1 but rather a result of their linguistic background, which leads to “making different rhetorical choices to construct identity while maintaining text coherence in academic discourse” (Carrió-Pastor 2013: 193). Interestingly, in her contrastive study between two academic corpora (by native and non-native writers), the author did not find any significant difference in the frequency of use of contrastive connectors like however, which were used similarly by both groups. She found out that there was a lack of variety in the range of connectors employed by the non-native writers, in line with previous research.

Together with learners’ level, another variable that has long attracted scholars’ attention is gender. In the field of discourse markers, the work by Tavakoli and Karimnia (2017) is worth mentioning; they investigated the Iranian EFL learners’ use of discourse markers in connection with gender and their results show that female users tend to employ more discourse markers than their male counterparts. In a similar line, Alqahtani and Abdelhalim (2020) studied 60 academic essays written by EFL university students (30 by female and 30 by male students), with a focus on metadiscourse markers. They revealed a statistically significant difference between male and female students in using some interactive markers such as transitions, frame markers, and code glosses, with female students surpassing their male counterparts.

In the case of Spanish EFL learners, the study of gender has focused on lexical choices (Díez Prados 2010), the expression of emotion (Pérez-García and Sánchez 2020), or the use of the L1 during interaction (Azkarai 2015). Results seem not to be conclusive, with some of the previous authors reporting differences between genders. Nevertheless, in a more recent study on the written expression of EFL Mexican students, Núñez Mercado (2022) has found no significant difference in terms of discourse markers by the two genders. To the best of my knowledge, the study of contrastive connectors across levels and in connection with gender has not been tackled in the study of Spanish EFL learners.

3. Data and methods

The present paper intends to redress the previously mentioned imbalance by aiming to answer the following research questions:

RQ1. To what extent (if any) is the use of contrastive linking adverbials affected by the learners’ CEFR level? In other words, to what degree do higher-level students employ a wider range of linking adverbials in contrast to lower-level students? More specifically, I will be analysing two groups of contrastive linking adverbials: (i) the single adverbs however, nonetheless, nevertheless, yet, and still; and (ii) the prepositional phrases on the other hand, by contrast, and in contrast.

RQ2. To what extent (if any) does the learners’ gender affect their use of these contrastive linking adverbials (i.e., frequency of use and syntactic variety of use)?

In line with previous research (see Neff-van Aertselaer and Dafouz-Milne 2008; Rica Peromingo 2012; Carrió-Pastor 2013; Navarro Gil and Roquet Pugès 2020), it is hypothesised that the higher the learners’ level, the wider range of concessive expressions they will be able to employ and the more varied their discursive position. In other words, it is expected that B1 learners will more often resort to however in sentence-initial position while C1 learners are hypothesised to use other concessive adverbials such as nonetheless and deploy a wider range of discursive positions in the sentence (initial, middle, and final). B2 learners are predicted to stand in between the previous and following levels. Regarding gender, and according to prior research (see Tavakoli and Karimnia 2017; Alqahtani and Abdelhalim 2020), it is hypothesised that female learners will use contrastive connectors more frequently than their male counterparts while no differences are expected with regard to variety.

The data set employed in the present study is part of the FineDesc learner-based corpus (gathered by the FineDesc project2). This corpus includes the written compositions of EFL students who take official accreditation exams to certify their level in different language centres all over Spain. This factor is important as the candidates are taking part in a high stakes exam and often wish to do their best to pass and obtain their certification. All the candidates were asked to fill in a consent form, but to preserve their privacy all the exams have been transcribed and anonymised, numbered and coded according to the gender3 reported by the candidates themselves. Furthermore, to make sure the level of the students corresponds to the three levels under scrutiny (i.e., B1, B2, and C1), all the essays included in the corpus (both the general corpus and the sub-set here analysed) belong to students who passed the exam, hence obtaining a certification of their level. Finally, all the data thus compiled have been approved by the main researcher’s university ethical committee.

For the purposes of the current paper, all the selected writings belong to the opinion essay genre on different topics such as rural versus city life, the pros and cons of technology, or the advantages and disadvantages of bilingual education, among others. This choice was determined by the expectation that it is in this genre that learners are more likely to employ contrastive expressions. Table 1 sums up the gender and number of participants involved in each level. Table 2 presents the number of words in each of the three levels. The corpus is thus a convenience sample as it is informed by the candidates who passed each of the levels of the accreditation exam. Neither the number of candidates per level nor the gender could be determined by the researcher beforehand.

|

CEFR Level |

B1 level |

B2 level |

C1 level |

|||

|

Gender |

Female |

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

Male |

|

41 |

41 |

70 |

70 |

25 |

28 |

|

|

Total |

82 |

140 |

53 |

|||

Table 1: Corpus description (levels and participants)

|

Level |

B1 level |

B2 level |

C1 level |

TOTAL |

|

Words |

12,202 |

30,846 |

14,894 |

57,942 |

Table 2: Corpus description (number of words per level)

Though admitting that the dataset is limited, it is possible to approach it from a mixed-methods perspective (see Ghadessy et al. 2008). The quantitative part has been carried out with the aid of Sketch Engine, where the corpus was uploaded. However, given that some of the students’ linguistic productions were not always automatically retrieved, a manual retrieval was included. For example, on the other hand may also appear as on another hand, which made the manual retrieval essential. Likewise, adverbs like yet or still could not be retrieved using exclusively automatic methods as they are polysemous and, besides contrast, they may also function as time relationship adverbials (Quirk et al. 1985: 194). More specifically, I have focused on the frequency, discursive position, and use of the following contrastive linking adverbials: the adverbs however, nonetheless, nevertheless, yet, and still and the prepositional phrases on the other hand, in contrast, and by contrast. Excel was used to normalise frequencies per thousand words (ptw) so as to make the subcorpora comparable, given their different sizes.4

4. Results and analysis

For the sake of clarity, Section 4 has been divided into three sub-sections, the first two of which align with the corresponding research questions. Thus, Section 4.1 focuses on the use of contrastive linking adverbials across the three levels under study (B1, B2, and C1), while Section 4.2 focuses on the contrast between both genders. Finally, Section 4.3 includes a summarising general discussion and links results with the pertinent descriptors of the CEFR and Companion Volume (2020).

4.1. Contrastive linking adverbials across levels

Table 3 offers an overview of the frequency of all the adverbial links under scrutiny across the three levels. The left column shows the raw number of occurrences, and the right column presents the normalised frequency per thousand words (ptw). Still and by contrast produced no hits. In the case of still, this was after disambiguation.

|

|

B1 |

B2 |

C1 |

|||

|

Linking adverbial |

Freq. (raw) |

Freq. (ptw) |

Freq. (raw) |

Freq. (ptw) |

Freq. (raw) |

Freq. (ptw) |

|

However |

20 |

1.639 |

51 |

1.653 |

20 |

1.342 |

|

Nevertheless |

3 |

0.245 |

13 |

0.421 |

8 |

0.537 |

|

Nonetheless |

1 |

0.081 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

0.201 |

|

Yet |

1 |

0.081 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

0.201 |

|

In contrast |

1 |

0.081 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0.067 |

|

On the other hand5 |

32 |

2.622 |

69 |

2.236 |

17 |

1.141 |

Table 3: Overview of frequency of use

As can be seen, B1 and B2 learners favour the use of on the other hand as their most frequent way to express contrast, followed by however. C1 students follow a similar pattern, with a preference for these two adverbial linkers, but they opt for the single adverb however slightly more frequently than on the other hand. The third most frequent linking adverbial across the three levels is nevertheless. While these results are to be expected in line with previous research, it is remarkable that B2 students are those that deploy the lowest degree of variation, limiting their options to the three adverbial linkers already mentioned; in contrast, B1 learners show a slightly more varied range, shadowing the patterns of C1 students, albeit at a lower frequency. As expected, C1 learners are those with a wider range of variety. The outcome of the chi-square test was significant (p=0.042).

In the following paragraphs, I will focus on each of these expressions individually according to its level of frequency in the dataset, namely, on the other hand, however, nevertheless, nonetheless, yet, and in contrast. The remaining two linking adverbials (i.e., still and by contrast) have no tokens in any of the three levels, but I will try to explain the plausible reasons for this absence.

As shown in Table 3, there is a progressive decrease in the use of on the other hand across the three levels, with B1 students using it also more frequently than however. The use seems to decrease by more than half when students reach C1 level (from 2.622 ptw in B1 to 1.141 ptw in C1). A plausible reason for such a drop might be the influence of instruction. For example, the Cambridge Writing Guide for C1 (Porras Wadley 2022) recommends using more formal linking phrases such as nevertheless or nonetheless. Instructors, as a result, may play an influential role in learners’ choices. For example, Schenck (2020) has shown that these differences between non-native and English native writers may be influenced by their instruction. In his study, he contrasted the writings of EFL Korean students receiving instruction from native-speaking teachers and those who were taught by non-native ones. His results show that students whose instruction was carried out by native teachers were able to express more nuanced opinions and employed a wider range of devices. His study, however, presents an imbalanced sample, as the group taught by native speakers amounts to 59 participants in contrast to 19 in the group that was not.

Furthermore, it is worth noting that only students at the highest level (C1) succeed in writing the connector correctly, while students at B1 occasionally make mistakes with the accompanying preposition, using prepositions like in and even by, as in examples6 (1) and (2), or employing another hand, as in (3):

(1) In the other hand, there are a lot of pitfalls. [9281F]

(2) By the other hand, it could make you lower your grades because of the lack of time for studying. [9299F]

(3) In another hand the game can be bad too if you use it bad the people stay all day sitting at home in from of their computers also they don’t practise any sport and they don’t do exercice, this can beeing development some disease. [6257F]

These errors, however, amount to 15.6 per cent of the B1 sub-corpus, which may indicate that most students learn the expression as a bundle. More remarkable is that students at B2 level still make the same mistake, although the wrong preposition is always in, as in examples (4) and (5) by a male and female learner, respectively:

(4) In the other hand, we can’t forget how important englis is now a days. [70106M]

(5) In the other hand, we should keep in mind that not all students have the same learning skills. [10515F]

Although these cases amount to 13 per cent of the sub-corpus (nine out of 69 tokens), it shows that for these learners, it might have become a fossilised error. This connector, albeit used slightly less frequently at this level (0.20% of the sub-corpus) is still rather common among these learners to express contrast, while C1 students show a clear tendency to avoid it, maybe as a result of the aforementioned influence of instruction. These results are in line with Rica Peromingo (2012), whose analysis of Spanish EFL students’ written compositions also revealed a preference for on the other hand among B1 and B2 learners.

As can be observed in Table 3, however is the linking adverbial most favoured by C1 learners (1.342 ptw), although both B1 and B2 levels also employ it frequently (1.639 ptw and 1.653 ptw, respectively). However, there are discursive differences in its use. Thus, when exploring concordances, it is observed that at B1 level, students invariably place however at the beginning of the sentence, after a period and followed by a comma, as in examples (6) and (7) by a female and male learner, respectively:

(6) will be shown among students of this kind. They’ll also learn time management, decision making and planning skills. However, it should be taken into consideration that working while studying could bring lack of motivation, cognitive fatigue […] [9276F]

(7) As students, we have to work hard to pass the exams and take as much knowledge as it its possible. However, everybody knows that the university studetns have a lot of free time.

At this level, students do not seem to be aware of the fact that this adverb can also be placed in middle- and final-sentence position. This could be a result of instruction, as this is the most frequent position exemplified by model texts in didactic materials, which seems to ‘prime’ students (see Leedham and Cai 2013).

When compared with B2-level students, there is a small attempt at placing the adverb in mid-sentence position (seven tokens out of 51), even if this is mostly done incorrectly and there are punctuation errors, as in examples (8) and (9) by a female and male learner, respectively. There is, however, one case where the student uses it appropriately, in example (10):

(8) people of other country, improve your CV (...) In short I will say that is very benefit study in a bilingual education however also have the disadvantage that some students do not learn the subject properly. [70100F]

(9) is true that language is a very important addition on your CV. In my opinion, I think bilingual education could be great, however if I could choose, I will only study in other language the last year of my degree. [70140M]

(10) Some people think that schools in our country should be bilingual, others, however, think that this type of education is not necessary for their kids. [70119F]

In any case, and despite the errors, students at this level seem to be aware of the possibility to place the adverb in a position other than the beginning of the sentence, even if this still remains the most favoured option (with 44 out of 51 tokens). Interestingly, users at C1 return to what could arguably be described as a more conservative use, as they place all the tokens in initial position.

The use of nevertheless increases with proficiency, with C1 learners leading the way (0.537 ptw), followed by B2 (0.421 ptw) and B1 learners (0.245 ptw). Independently of the level, however, learners always place nevertheless in the initial position, followed by a comma, as in examples (11) to (13), corresponding to B1, B2, and C1 level, respectively:

(11) Nevertheless, we have to be aware of the fanger that spending too much time playing can cause. [6258F]

(12) Nevertheless, for some people could be a disadvantage not to know other idioms [10150F]

(13) Nevertheless, some advocates against this conservation argue that keeping these huge ruins suppose the possibility of exposing the population to a real danger, on the grounds of the careless state of this ‘old ladies’. [900016M]

Interestingly, the three adverbial linkers already commented in the previous paragraphs (i.e., on the other hand, however, and nevertheless) are those to which all students resort, especially those at B2 level, since these are the only three options they employ throughout the dataset. This makes both B1 and C1 learners’ writings more varied in terms of contrastive adverbials. While this tendency is difficult to explain, a plausible reason might be that B2 students are less willing to take risks in order to ensure passing the exam, hence obtaining the corresponding certification. This specific instructional context (i.e., a high-stakes exam) might be rendering these students particularly unwilling to take risks, in line with Brown (2001: 63). According to this author, “many instructional contexts around the world do not encourage risk-taking; instead, they encourage correctness, right answers, and withhold ‘guesses’ until one is sure to be correct.” On the other hand, C1 students’ linguistic skills might be strong enough to deploy a wider range of connective devices while B1 learners might simply be more willing to take risks and impress their potential assessors.

Regarding nonetheless and yet, it is interesting to observe that they follow exactly the same pattern across the three levels. Thus, B2 students refrain from using them while B1 learners employ both with exactly the same low frequency (0.081) and C1 students use it slightly more frequently (0.201) but not particularly so. There are two plausible reasons for this. On the one hand, instructors might refrain from teaching nonetheless given that it is also sparsely employed by native and professional writers. For example, in the British Academic Written English Corpus (BAWE), nonetheless has a frequency of 0.0032 per cent per million words in contrast to however, with a frequency of 0.15 per cent. Hence, instructors might consider it too formal and infrequent to be taught. On the other hand, this group of B2 students might also be lower risk-takers, especially in this specific context of a high-stakes examination (Brown 2001).

The case of yet is also worth commenting on. Given the polysemy of the term, which can also be employed as a time adverb, learners might avoid using it as a contrastive adverbial. In contrast, native speakers seem to resort to it so as to widen the range of contrastive devices in their writings (Zhang 2021). In its contrastive use, yet is characterised by sentence-initial position, and by being followed by a pause indicated by the punctuation sign of a comma.

Results show that contrastive yet is employed just on one occasion by a male B1 learner, as illustrated in example (14). Its ratio is thus extremely low (0.00003):

(14) Europe has been learnt in the study culture, yet how much inportance have in our future? [9294M]

In the case of B2, there are no tokens of this connector, while its number increases to three tokens at C1 level, as illustrated in examples (15) and (16), by a female and male learner, respectively:

(15) Yet, a question needs raising here: What kind of city we want? [600004F]

(16) And yet, we vote blind. [900012M]

Albeit at a low frequency, there is nonetheless an increase in the number of tokens, which shows that students at lower and higher levels are either more willing to take risks or more confident in their linguistic ability. At B2 level, they seem to remain more insecure, which could explain why they resort to ‘safer’ options, even if they might be aware of other alternatives.

Against initial expectations, the use of in contrast is also extremely low, with a frequency of 0.081 among B1 learners and 0.067 among C1 students. Given the similarity with the Spanish phrase en contraste, I expected a positive language transfer from the participants’ L1 to their EFL writings. This might explain why B1 learners employ the phrase even more frequently than C1 participants, as they might be translating it from their Spanish mother tongue. As argued by Wanderley and Demmans (2020), proficiency raises a learner’s awareness of L2 rules and their application while less skilled learners (B1 students in our corpus) tend to employ transfer more frequently. Regarding the use of still as a contrastive connector, there are no occurrences in any of the three sub-corpora, which shows that learners may either be unaware of its contrastive meaning or unwilling to risk its use given that they feel safer employing other alternatives to express contrast, such as however or on the other hand, in line with previous studies like Zhang (2021), who reports an underuse of still and yet by his Chinese EFL participants in contrast to native users. Finally, there are no occurrences of by contrast in any of the three levels. This absence seems unexpected, as this expression might be more related to the students’ own L1. It is difficult to explain why they might be refraining from using it, but it might be due to the belief that this is a calque from Spanish and could hence be negatively assessed by the examiners. In fact, previous research has consistently shown that Spanish EFL learners tend to avoid cognates due to different reasons (e.g., different contextual uses, different frequency of use, different meaning despite a common etymology) to the extent that, according to Scarcella and Zimmerman (2005: 125), “L2 students who speak Spanish as a first language might avoid them in formal English writing” (see also Whitley 2002).

4.2. Gender and use of contrastive linking adverbials

Table 4 summarises the frequency of use according to the participants’ gender. To quantify results, all the writings by female and male students have been respectively added up according to the writers’ gender, independently of their level. All in all, the female dataset amounts to 29,629 words and the male one to 28,313 words. As in Section 5.1, frequencies have been normalised per thousand words to allow for comparison between the two genders. The column on the left presents the raw number of occurrences while that on the right displays the normalised frequency per gender.

|

|

Female learners |

Male learners |

||

|

Linking adv. |

Freq. (raw) |

Freq. (ptw) |

Freq. (raw) |

Freq. (ptw) |

|

However |

78 |

2.633 |

43 |

1.519 |

|

Nevertheless |

18 |

0.608 |

9 |

0.318 |

|

Nonetheless |

3 |

0.101 |

1 |

0.035 |

|

Yet |

1 |

0.034 |

2 |

0.071 |

|

In contrast |

1 |

0.034 |

1 |

0.035 |

|

On the other hand |

63 |

2.126 |

55 |

1.943 |

Table 4: Frequency of use according to gender

As can be observed in Table 4, female learners tend to employ more linking adverbials than their male counterparts, occasionally doubling the latter’s use. This seems to align with previous research that claims that female learners tend to employ more connectors than male learners (Winkler 2008; Tavakoli and Karimnia 2017; Alqahtani and Abdelhalim 2020). A chi-square test, however, has shown that the differences between both genders are not statistically significant (p=0.419). In fact, gender difference in discourse markers use has rendered contradictory results. For example, Azeez et al. (2023) report a higher use of discourse markers by male than by female participants, although their study is based on the fictional characters of Shaw’s theatre play Arms and the Man rather than on real speakers/writers. Still, Núñez Mercado (2022), in a more recent study on the written expression of EFL Mexican students, found no significant difference in terms of discourse markers by the two genders, in line with the results found in the current study, where differences are not statistically significant either. Regarding variety, results do not seem affected by the participants’ gender, both male and female students resorting mainly to three adverbial linkers, namely, however, on the other hand, and nevertheless, while polysemous expressions like still or yet are scarcely used or not used at all. Cognates such as by contrast or in contrast also tend to be avoided by these participants. As already mentioned, this might be due to the students’ fear that these expressions are negatively evaluated as calques (Whitley 2002).

4.3 Expressing contrast according to the CEFR/CV

According to the CEFR/CV (2020), the ability to express contrast by means of adverbial links or connectors should already be present at B1 level, the main difference with higher levels being the range of use by learners. In other words, the higher the level, the more varied the connectors are expected to be. More specifically, the CEFR/CV sums up these differences as shown in Figure 1. As already pointed out, the difference between B1 and B2 seems clearer as B1 learners are expected to “use a limited number of cohesive devices” while B2 learners should be able to “use a range of linking words and cohesive devices” (my emphasis). This difference is vaguer when it comes to the contrast between B2 and C1 students, as the latter are supposed to use “a variety of cohesive devices”, the difference between “a range” and “a variety” arguably unhelpful for learners, evaluators, and teachers.

Figure 1: Descriptors for Coherence and Cohesion (CV, 2020: 142)

As already discussed in Section 5.1, on the other hand is widely used by B1 and B2 students (2.622 ptw and 2.236 ptw, respectively) in line with previous research such as Rica Peromingo (2012), whose results report the same tendency among these two levels. However is also widely employed by the three levels, with a higher frequency by C1 students, also in line with previous research (Zhang 2021). The frequency of more formal contrastive devices such as nevertheless and nonetheless is reversed when it comes to nonetheless, with zero occurrences at B2. Polysemous devices such as yet or still are only employed by higher level students, although at a low frequency (2%).

The results of the present study do not seem to support this distinction, as B1 learners use as many linking devices as students at B2 and even display a wider variety, akin to that of C1 students. Thus, out of the eight contrastive linking adverbials under scrutiny, B1 and C1 students employ six (on the other hand, however, nevertheless, nonetheless, yet, and in contrast). By contrast, B2 students show the same frequency of their counterparts but a marked lack of variety, with only a repertoire limited to three linking adverbials (on the other hand, however, and nevertheless).

Interestingly, these results seem to point to B2 learners being less ‘adventurous’ than those at lower and higher levels. Indeed, they seem to prefer using safer (but fewer) options which they know well rather than displaying a variety of cohesive devices as the CEFR/CV points out. Unfortunately, and to the best of my knowledge, there is no prior research on the subject. As a result, any conclusions about this group of B2 students remain speculative. Nevertheless, this gap may open up interesting avenues for future research in other text-types (for example, to explore whether this behaviour also appears in genres such as personal emails or narratives, or whether it is specific to more formal argumentative essays). As Tabari (2022) argues, there are other factors that might affect the learners’ writing results. In his study, he found that task planning could mitigate the content and organisation demands on L2 writers’ cognitive processes and consequently enable the allocation of proper attentional resources to other aspects of the writing system and processes, hence enhancing writing products. Since the participants in the present study were under the pressure of taking a high-stakes exam, this might explain why they tend to overuse familiar connectors like however even at higher levels of linguistic proficiency like C1.

As already discussed in Section 5.1, on the other hand is widely used by B1 and B2 students (2.622 ptw and 2.236 ptw, respectively) in line with previous research such as Rica Peromingo (2012), whose results report the same tendency among these two levels. In a more recent study, Faya-Cerqueiro and Martín Macho-Harrison (2022) find similar results, with on the other hand (and wrongly constructed expressions like *in the other hand) being overwhelmingly employed, not only to show contrast but also to enumerate (often as an adjacent pair with on the one hand).

However is also widely employed by the three levels, with a higher frequency by C1 students, also in line with previous research (Zhang 2021). In fact, textbooks may also encourage its use as a contrastive device. For example, the Oxford EAP B1 textbook (de Chazal and Rogers 2013a: 158) includes the following linking words to express contrast: but, on the other hand, despite, even if, even though, and however and the same list is present in the edition for B2 learners (de Chazal and Rogers 2013b). Furthermore, its placement seems rather fixed in initial-sentence position, especially by B1 and B2 learners, rather than expert writers’ rhematic position.

More formal contrastive devices such as nevertheless and nonetheless are, however, much less frequent and even absent in the case of B2 students. This aligns with previous research on Spanish EFL writers, who underuse nevertheless when compared with native writers. For example, Carrió-Pastor (2013: 196–197) found that her non-native writers employed nevertheless in 1.2 per cent of the cases in contrast to native writers (2.3%). Similar results were obtained for nonetheless, which although scarcely used by both cohorts, was employed 0.7 per cent by native writers versus 0.4 per cent by non-native ones.

As for polysemous devices such as yet or still, results show that they are either sparsely used or not used at all by all three groups. This absence might be due to two main reasons. On the one hand, their polysemous nature might confuse learners, who are more familiar with these expressions as time adverbials. On the other, instructors and teaching materials may also play a central role.

The role of instruction should not hence be underestimated, for example, regarding the transferable use of L1 strategies. As argued by Faya-Cerqueiro and Martín Macho-Harrison (2022: n.a), teachers should advocate for the need to adopt a pedagogic approach that favours translanguaging and boosts positive language transfer to “extrapolate certain abilities” already acquired in their L1 to their EFL (see also Cenoz et al. 2022). Furthermore, resorting to their knowledge of the L1 might become extremely helpful when tackling writing tasks in line with previous research (see Plata-Ramírez 2016). Fostering students’ metalinguistic reflection might render positive results, especially in the use of cognates like in contrast or by contrast, which students might be avoiding in the fear that they are calques rather than correct linking devices often employed by native writers.

5. Conclusion

The present paper aimed to answer the following research questions, repeated here for the sake of clarity:

RQ1. To what extent (if any) is the use of contrastive linking adverbials affected by the learners’ CEFR level? In other words, to what degree do higher-level students employ a wider range of linking adverbials in contrast to lower-level students? More specifically, I will be analysing two groups of contrastive linking adverbials: (i) the single adverbs however, nonetheless, nevertheless, yet and still; and (ii) the prepositional phrases on the other hand, by contrast, and in contrast.

RQ2. To what extent (if any) does the learners’ gender affect their use of these contrastive linking adverbials (i.e., frequency of use and syntactic variety of use)?

In response to the first question, results show that there is a statistically significant relationship between the students’ level and their use of contrastive linking adverbials, which would confirm the first hypothesis. Nevertheless, there is a progressive decrease in terms of frequency in the use of linking adverbials as students’ level increases. Thus, normalised frequencies show that B1 learners use a further amount of linking adverbials (4.753 ptw), in contrast to B2 (4.311 ptw) and C1 (3.491 ptw). This could be due to the fact that higher-level students resort to a wider variety of linguistic strategies to express contrast, including both coordination and subordination, which future research intends to explore. Regarding variety, and against expectations, students at B1 level display the same range of linking adverbials than those at C1 (albeit at lower frequencies), while B2 students’ repertoire is limited to three of the eight expressions under analysis. Polysemous devices such as still and yet seem too complex for students to employ, also independently of the level. This could be due to the fact that the learners of the present dataset were taking a high-stakes exam, which might lead them to more conservative and ‘safer’ options rather than more ‘adventurous’ ones. As already mentioned, the role of instruction should not be underestimated either.

Regarding the second question, gender does not seem to play any role in the frequency and range of these learners’ use of contrastive devices. In fact, despite minor differences which are not statistically significant, both male and female learners seem to resort to the same kind of devices at the three levels, even if female writers tend to a higher frequency of use.

Admittedly, this paper is not without limitations, especially as regards the size of the dataset and the fact that I have focused exclusively on eight linking adverbials and not on other linguistic devices to express contrast, such as subordinating conjunctions like although, or coordinating ones like but, which have been shown to be extensively used at B1 level (see Lahuerta Martínez 2002). On the other hand, the present dataset has not been contrasted with an L1 corpus (e.g., the BAWE) to observe whether native writers also underuse or overuse these linking adverbials. Future research from a cross-linguistic approach might shed light in this regard.

References

Ahmed, Abdelhamid M., Xiao Zhang, Lameya M. Rezk and William S. Pearson. 2023. Transition markers in Qatari university students’ argumentative writing: A cross-linguistic analysis of L1 Arabic and L2 English. Ampersand 10: 100110.

Alqahtani, Sahar Nafel and Safaa M. Abdelhalim. 2020. Gender-based study of interactive metadiscourse markers in EFL academic writing. Theory and Practice in Language Studies 10/10: 1315–1325.

Altenberg, Bengt and Marie Tapper. 1998. The use of adverbial connectors in advanced Swedish learners’ written English. In Sylviane Granger ed. Learner English on Computer. London: Longman, 80–93.

Appel, Randy. 2020. An exploratory analysis of linking adverbials in post-secondary texts from L1 Arabic, Chinese, and English writers. Ampersand 7: 100070.

Azeez, Abbas Ibrahim, Ayad Hameed Mahmoud and Ahmed Adel Nouri. 2023. A multi-perspective study of discourse markers: An attempt to sort out the muddle among EFL teachers-students. EDUCASIA: Jurnal Pendidikan, Pengajaran, dan Pembelajaran 8/1: 25–48.

Azkarai, Agurtzane. 2015. L1 use in EFL task-based interaction: A matter of gender? European Journal of Applied Linguistics 3/2: 159–179.

Biber, Douglas, Stig Johansson, Geoffrey Leech, Susan Conrad, and Edward Finegan. 2021. Grammar of Spoken and Written English. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Blakemore, Diane. 2006. Discourse markers. In Laurence R. Horn and Gregory Ward eds. The Handbook of Pragmatics. London: Blackwell Publishing, 221–240.

Brown, H. Douglas. 2001. Teaching by Principles: An Interactive Approach to Language Pedagogy. New York: Addition Wesley: Longman, Inc.

Carrió-Pastor, María Luisa. 2013. A contrastive study of the variation of sentence connectors in academic English. Journal of English for Academic Purposes 12/3: 192–202.

Celce-Murcia, Marianne and Diane Larsen-Freeman. 1999. The Grammar Book. Boston: Heinle & Heinle Publishers.

Cenoz, Jasone, Oihana Leonet and Durk Gorter. 2022. Developing cognate awareness through pedagogical translanguaging. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 25/8: 2759–2773.

Council of Europe. Council for Cultural Co-operation. Education Committee. Modern Languages Division. 2001. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Council of Europe. 2020. Companion Volume. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cowan, Ron. 2008. Discourse connectors and discourse markers. In Ron Cowan ed. The Teacher’s Grammar of English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 615–634.

de Chazal, Edward and Louis Rogers. 2013a. Oxford EAP. Intermediate B1+. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

de Chazal, Edward and Louis Rogers. 2013b. Oxford EAP. Upper Intermediate B2. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Díez Prados, Mercedes. 2010. Gender and L1 influence on EFL learners’ lexicon. In Rosa Mª Jiménez Catalán ed. Gender Perspectives on Vocabulary in Foreign and Second Languages. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 44–73.

Faya-Cerqueiro, Fátima and Ana Martín Macho-Harrison. 2022. Uso de conectores en la redacción de textos argumentativos: Comparación entre L1 y L2. Ocnos. Journal of Reading Research 21/2.

Ghadessy, Mohsen, Robert L. Roseberry and Alex Henry. 2008. Small Corpus Studies and ELT. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Granger, Sylviane and Stephanie Tyson. 1996. Connector usage in the English essay writing of native and non‐native EFL speakers of English. World Englishes 15/1: 17–27.

Granger, Sylviane. 2015. Contrastive interlanguage analysis: A reappraisal. International Journal of Learner Corpus Research 1/1: 7–24.

Gilquin, Gaëtanelle and Magali Paquot. 2008. Too chatty: Learner academic writing and register variation. English Text Construction 1/1: 41–61.

Ha, Myung-Jeong. 2016. Linking adverbials in first-year Korean university EFL learners’ writing: A corpus-informed analysis. Computer Assisted Language Learning 29/6: 1090–1101.

Hasselgren, Angela. 1994. Lexical teddy bears and advanced learners: A study into the ways Norwegian students cope with English vocabulary. International Journal of Applied Linguistics 4/2: 237–258.

Hosseinpur, Rasoul Mohammad and Hossein Hosseini Pour. 2022. Adversative connectors use in EFL and native students’ writing: A contrastive analysis. The Electronic Journal for English as a Second Language 26/1.

Huddleston, Rodney and Geoffrey Pullum. 2002. The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jiménez Catalán, Rosa María and Julieta Ojeda Alba. 2014. Diagnóstico de las dificultades en el uso de los conectores en una tarea escrita por parte de aprendices de inglés como lengua extranjera: Estrategias de corrección. Didáctica [Lengua y Literatura] 26: 197–217.

Lahuerta Martínez, Ana Cristina. 2002. The use of discourse markers in EFL learners’ writing. Revista Alicantina de Estudios Ingleses 15/4: 123–132.

Lee, Kent. 2013. Korean ESL learners’ use of connectors in English academic writing. English Language Teaching 25/2: 81–103.

Lee, Kent. 2020. Chinese ESL writers’ use of English contrastive markers. English Language Teaching 32/4: 89–110.

Leedham, Maria and Guozhi Cai. 2013. Besides … on the other hand: Using a corpus approach to explore the influence of teaching materials on Chinese students’ use of linking adverbials. Journal of Second Language Writing 22/4: 374–389.

Modhish, Abdulhafeed Saif. 2012. Use of discourse markers in the composition writings of Arab EFL learners. English Language Teaching 5/5: 56–61.

Mora Díaz, Luz Mary and Yeimmy Gómez Orjuela. 2021. Understanding the English language through a creative writing workshop: Adjectives and adverbs essential for EFL learners. Shimmering Words: Research and Pedagogy E-journal 11: 52–73.

Narita, Masumi, Chieko Sato and Masatoshi Sugiura. 2004. Connector usage in the English essay writing of Japanese EFL learners. Language Resources and Evaluation Conference 27/1: 1171–1174.

Navarro Gil, Noelia and Helena Roquet Pugès. 2020. Linking or delinking of ideas? Revista Española de Lingüística Aplicada 33/2: 505–535.

Neff-van Aertselaer, JoAnne and Emma Dafouz-Milne. 2008. Argumentation patterns in different languages: An analysis of metadiscourse markers in English and Spanish texts. In Martin Putz and JoAnne Neff eds. Developing Contrastive Pragmatics Interlanguage and Cross-cultural Perspectives. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 87–102.

Núñez Mercado, Carlos. 2022. Male and female BA students’ use of discourse markers: A corpus-based study. Lenguas en Contexto 13: 4–12.

Park, Yong-Yae. 2013. Korean college EFL students’ use of contrastive conjunctions in argumentative writing. English Teaching 68(2): 263–284.

Pérez-García, Elisa and Mª Jesús Sánchez. 2020. Emotions as a linguistic category: Perception and expression of emotions by Spanish EFL students. Language, Culture and Curriculum 33/3: 274–289.

Pérez-Paredes, Pascual, María Sánchez-Tornel and José Mª Alcaraz Calero. 2012. Learners’ search patterns during corpus-based focus-on-form activities: A study on hands-on concordancing. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 17/4: 482–515.

Plata-Ramírez, José Miguel. 2016. Language switching: Exploring writers’ perceptions on the use of their L1s in the L2 writing process. Revista Internacional de Lenguas Extranjeras 5: 47–77.

Porras Wadley, Luis. 2022. The Ultimate CAE Writing Guide for C1 Cambridge. Granada: KSE Academy.

Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech and Jan Svartvik. 1985. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman.

Rica Peromingo, Juan Pedro. 2012. Corpus analysis and phraseology. Linguistics and the Human Sciences 6/3: 321–343.

Scarcella, Robin Cameron and Cheryl Boyd Zimmerman. 2005. Cognates, cognition, and writing: An investigation of the use of cognates by university second-language learners. In Andrea Tyler, Mari Takada, Yiyoung Kim and Diana Marinova eds. Language in Use: Cognitive and Discourse Perspectives on Language and Language Learning. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 123–136.

Schenck, Andrew. 2020. Examining the influence of native and non-native English-speaking teachers on Korean EFL writing. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education 5/1: 2–17.

Tabari, Mahmoud Abdi. 2022. Investigating the interactions between L2 writing processes and products under different task planning time conditions. Journal of Second Language Writing 55: 100871.

Tankó, Gyula. 2008. Composition: The use of adverbial connectors in Hungarian university students’ argumentative essays. In John Sinclair ed. How to Use Corpora in Language Teaching. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 157–181.

Tavakoli, Mahboobeh and Amin Karimnia. 2017. Dominant and gender-specific tendencies in the use of discourse markers: Insights from EFL learners. World Journal of English Language 7/2: 1-9.

Wanderley, Leticia Farias and Carrie Demmans Epp. 2020. Identifying negative language transfer in writing to increase English as a Second Language learners’ metalinguistic awareness. In Vitomir Kovanović, Maren Scheffel, Niels Pinkwart and Katrien Verbert eds. Companion Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge (LAK20). Frankfurt: The University of Frankfurt, 722–725.

Whitley, Melvin Stanley. 2002. Spanish/English Contrasts: A Course in Spanish Linguistics. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press.

Winkler, Elizabeth Grace. 2008. A gender-based analysis of discourse markers in Limonese Creole. Sargasso: A Journal of Caribbean Literature, Language & Culture, Special Issue: Linguistic Explorations of Gender & Sexuality 1: 53–72.

Yilmaz, Ercan and Kenan Dikilitas. 2017. EFL learners’ uses of adverbs in argumentative essays. Novitas-ROYAL (Research on Youth and Language) 11/1: 69–87.

Yoon, Choongil. 2019. On the other hand: A comparative study of its use by Korean EFL students, NS students and published writers. Journal of Language Sciences 26/2: 273–297.

Zhang, Yan. 2021. Adversative and Concessive Conjunctions in EFL Writing: Corpus-based Description and Rhetorical Structure Analysis. Berlin: Springer.

Notes

1 This research has been funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities and the National Research Agency. Grant PID2020-117041GA-I00, funded MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 [Back]

2 https://web.ujaen.es/investiga/finedesc/index.php [Back]

3 Participants were provided with the male, female, non-binary, and rather not say options when asked about their gender. All the participants in the present dataset reported to be either male or female. [Back]

4 Given the size of the dataset, it was decided to normalise per thousand words rather than per million words. [Back]

5 For the purposes of the current research, only the phrase expressing contrast has been considered, including also grammatically wrong expressions such as in the other hand or on another hand, which were manually retrieved but also quantified and included in this normalised frequency. Future research might zero in on its other uses such as expressing an alternative. [Back]

6 Each example is reproduced as it appears in the original text, followed by a number indicating the number of student and their self-reported gender. Thus, F stands for female and M for male. The word under scrutiny is in bold for the sake of clarity. [Back]

Corresponding author

Carmen Maíz-Arévalo

Complutense University of Madrid

Department of English Studies

Plaza Menéndez Pelayo s/n

ES-28040 Madrid

Spain

E-mail: cmaizare@ucm.es

received: February 2025

accepted: May 2025